The Regiment is on the March

GNI DAT 306

Recorded: Studenice, Styria, 2005

Played by: Frajhajm brass band

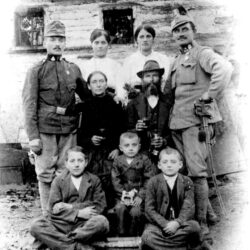

The sound images identified with the military came into folk music primarily through marches. One of the most frequent was the Holchakermarš. In the recording it is played by the Frajhajm brass band, which consists of thirteen self-taught members. It is also interesting because of its tradition; since its very beginning in 1827, it has been connected with the name of the Jurič family. [24]

Ph 2545

Recorded: Judenburg, Austria, 1916

Sung by: Rudolf Knez and group of men

Released on the compact disc Gesamtausgabe der Historischen Bestände 1899–1950, Serie 4: Soldatenlieder der k. u. k. Armee, PHA CD 11/2, no. 29

The wax-disc recordings of Slovenian soldiers singing are among the oldest Slovenian audio recordings. They were made as part of Vienna’s Phonogrammarchiv program. Among these recordings, which documented the singing of soldiers from all of the nations of Austria during the First World War, the Slovenian songs are the most moving. Two years later, Judenburg was the scene of the largest revolt by Slovenian soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army.

GNI M 21.813

Recorded: Raka, Lower Carniola, 1958

Sung by: Franc Cemič

The story of the Battle of Sisak in 1593, an important victory over the Turks, has also been preserved in the song of the common people in this heroic ballad about Adam Ravbar. It belongs to the group of songs that faded most quickly with the elimination of illiteracy and was saved only through early transcriptions. [25] The second stanza of this partially preserved version mentions the possibility of buying soldiers’ freedom, which had to correspond to the expenses for supporting a conscripted soldier (Čremošnik, 1939: 346).

GNI M 24.226

Recorded: Črenšovci, Prekmurje, 1961

Sung by: Matija Koštric

This song celebrates the capture of Belgrade in 1789 with the victory of Austrian Field Marshal Gideon Ernst von Laudon over the Turks. This victory was also known in folk tradition in German-speaking areas and through descriptions on pamphlets, but this Slovenian heroic song expresses a completely different creativity (SLP I: 92).

GNI M 26.078

Recorded: Stari trg ob Kolpi, Bela krajina, 1963

Sung by: Ivanka Štrbenc

From the 14th century onwards, during the time of mercenary armies, in addition to persuasion and trickery, soldiers were also attracted by the opportunity for gain and adventure. With the mention of yellow uniforms, this song preserves the folk memory of the purchase of soldiers for the Spanish mercenary army (Navratil, 1858: 100, Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 20). [26] It is also special because of the musical role it played at the beginnings of manifest expression of national consciousness in 1848. [27] For technical reasons, this version is not presented in its entirety on the audio publication.

GNI M 46.976

Recorded: Bizeljsko, Styria, 1997

Played by: Anton Zagmajster (diatonic accordion)

Among other melodies, this piece incorporates “Po jezeru bliz Triglava” (Along the Lake near Triglav), also known as “Na jezeru” (On the Lake), by Miroslav Vilhar. This popularized song, which marked the time of national self-awareness through its inclusion in various songs and instrumental arrangements, gives a special emphasis to the march.

GNI M 23.671

Recorded: Jastroblje, Špitalič, Upper Carniola, 1960

Sung by: Ančka Cencelj, Marija Šuštar, Francka Pistotnik

The content of this song clearly indicates when it was created; that is, during the time of universal military service or its reorganization after 1771. The strong effect of this measure marked a number of types of military songs whose first stanzas refer to nove novice ‘new news’, nove postave ‘new statutes’, or nove patente ‘new patents’, or personified the measure in line with the concepts of the common people: Kaj si je naš cesar zmislu ‘What has our emperor thought of’, Hudi glas iz Gradca gre ‘An ill voice is coming from Graz’, Pršle so z Gradca cajtinge ‘The newspapers came from Graz’ (Štrekelj, 1900–1903: 249–251, Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 26–53, 91, 153). The equality referred to in the first stanza was more of an illusion than a reality.

GNI M 46.711

Recorded: Veliki Trn, Lower Carniola, 1996

Sung by: Albin Kopina Sr., Marko Kopina, Martin Gorenc, Franc Lekše, Tone Janc, Jože Lekše Sr., Albin Kopina Jr., Jože Lekše Jr.

This song is distinguished by its melancholy response to conscription. Although lifelong military service had been abandoned in the 19th century, when the song was created, it still symbolically stood for departure for wars with the French and in northern Italy (Kumer, 1992:81). Judging from one version, [28] it was created between 1811 and 1845, during the time of fourteen-year military service, whereas some versions mention eight years of service (Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 11–112), which applied between 1845 and 1866 (Čremošnik 1939: 354).

GNI M 23.520

Recorded: Češnjice v Tuhinju, Upper Carniola, 1960

Sung by: Jože Jeglič

Between the motif of departure for military service and the rebellious conclusion that frame this song, the “damned pen” (prešmentano pero) that signed young men “into military service” (k vojaškemu stanú) stands out. The song thus inadvertently draws attention to the selection and its inequality that stemmed from social stratification.

GNI M 27.748

Recorded: Osluševci, Styria, 1965

Sung by: Honza Korpar, Tona Korpar, Stanko Korpar

Recruits’ leave-taking from their homes, sweethearts, and friends was not only more solemn when accompanied by song, but also easier because singing together was the best way to overcome the anguish of separation. This anguish was also overcome by emphasizing the importance of their new roles, most clearly marked by bouquets of flowers, or pušeljci, also mentioned in this song. The bouquets also represent a connection to their girlfriends, and in some places the men not accepted for military service had to turn over all of their recruitment decorations to those that were accepted.

GNI M 23.316

Recorded: Ponikve na Krasu, Littoral, 1959

Sung by: Jože Pegan, Mario Pegan, Milan Jazbec, Silvan Hec

The thoughts of this song eloquently express how the recruits and soldiers overcame the pain of farewell: . . . da veselo zapojèmo to prežalostno slovo (‘. . . we happily sing out this sad, sad farewell’). This song preserves a rare example of melodic ornamentation.

GNI M 39.161

Recorded: Ebriach, Carinthia (Austria), 1979

Sung by: Liza Karničar, Marta Polanšek, Marija Brumnik, Justi Polanšek, Johan Brumnik, Folti Karničar, Pepi Brumnik, Valentin Polanšek

Today it is difficult to recognize the connection between a love song with a motif of farewell and military songs, but when the recording was made this song was still known as a military song in Carinthia. The song originally referred to departure for military service.

GNI M 44.631

Recorded: Ješenca, Styria, 1988

Sung by: Rozika Ofič

Military songs provided courage even at the most difficult moments when confronting danger, and expressed pride at the same time. With such feelings, men and boys could more easily bear their anxiety and separation from home. Slomšek’s poem “Leži, leži ravno polje” – which was published in Drobtinice in 1851 under the title “Popotnica vojaška” (Military Farewell) (Slomšek, 1851) – was also dedicated to this. It was intended to be sung to the melody of the song about Laudon (Ahacel, 1838: 21), which was completely different from the melody in this version. Because of its known authorship, the song is not included in the collection Slovenske narodne pesmi (Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 212).

GNI M 22.295

Recorded: Solčava, Styria, 1958

Sung by: Angela Robnik, Joža Klemenšek, Malka Skovic, Ivan Klemenšek

This song from a girl’s perspective recalls the era of warfare with the French; it expresses a proud view of the young man and at the same time hope for deliverance, almost certainly supernatural. There were many reasons for this type of thought: As Austrian soldiers, Slovenians first fought against Napoleon, and then they were included in Napoleon’s army. In 1812 a Slovenian infantry regiment left with Napoleon for Russia, never to return (Švajncer, 1992: 70).

GNI M 21.887

Recorded: Raka, Lower Carniola, 1958

Sung by: Franc Cemič

The image of the emperor in this greatly truncated song reveals the common people’s conceptualization of the emperor and the military authorities. In a more complete version of this song, the emperor stands guard with his crown in his hands (Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 91).

GNI M 25.538

Recorded: Zagorica, Dobrepolje, Lower Carniola, 1963

Sung by: Ančka Kralj

Young men that avoided military service were condemned to total exclusion from society. This song expresses these dilemmas and decisions in a simple and very sensitive manner.

GNI M 43.310

Recorded: Šentvid pri Stični, Lower Carniola, 1986

Bells played by: Bell chimers from Višnja Gora, Lower Carniola

This bell chiming melody titled Radetzky is based on the rhythm of Johann Strauss Sr.’s Radetzky March (Kumer, 1992: 18). The chiming highlights the significance of bells not only in experiencing holidays, but also their symbolic role at serious times during war.

GNI M 22.543

Recorded: Luče, Styria, 1958

Sung by: Marija Jež

The war with Italy and pride at the victory of the Austrian Army at the first Battle of Custoza in 1848 (Kumer, 1992: 18) were shaped by the language of folk song into a characteristic military song. This song features the image of Count Radetzky, and also emphasizes the heroism of young Slovenian men. This heroism was also recorded in the annals of history when the field marshal Baron D’Aspre removed his hat before the soldiers of the 47th Slovenian-Styrian infantry regiment as a sign of exceptional respect (Švajncer, 1992: 78).

GNI M 31.312

Recorded: Felsőszölnök, Rába Valley (Hungary), 1970

Sung by: Julija Bajzek, Ilonka Bajzek, Ana Šulič, Marija Časar

This ballad about the faithfulness of a girl whose love a young man tests as a pretext is part of older (and perhaps even late medieval) tradition and is very widespread throughout Europe (Golež, 1998: 469). The popularity of this song is also shown by the large number of Slovenian versions (SLP IV 1998: 380–468). The tense two-part singing is characteristic of the extreme eastern part of Slovenian ethnic territory.

GNI M 22.134

Recorded: Markovci, Prekmurje, 1958

Sung by: Ludvik Časar

Red clouds, [29] the thunder of the guns, and the rhetorical question of who will do the work at home during military service are very familiar motifs in military songs today. They are also preserved in this song from Prekmurje.

GNI M 23.448

Recorded: Zgornji Tuhinj, Upper Carniola, 1960

Sung by: Jernej Kadunc, Ivan Drolc

The historical framework of this song is the Austro-Prussian war of 1866. Slovenians also distinguished themselves in this war: for example, despite severe wounds, the drummer Jurij Falež from Ješenca near Maribor drummed the attack on his drum until he bled to death (Švajncer, 1992: 88). The experience of distress in the song is expressed through simple folk metaphor and, as an old military song, the song even manages a humorous tone.

GNI M 46.422

Recorded: Britof, Upper Carniola, 1996

Sung by: Francka Čimžar, Pavla Pičman

Today one of the best-known military songs was originally part of a song about a volunteer’s remorse. [30] It dates from the time of the mercenary armies, but its symbolic communicativeness has given it a meaning that transcends time. In addition to the army drum, the song is also marked by the army saber. In the infantry the saber was in use only between 1765 and 1798 (Čremošnik, 1939: 354); that is, when universal compulsory military service was introduced. This is when most traditional military songs were created, and therefore the sabljica pripasana ‘saber at one’s side’ became and remains a symbol of military service.

GNI M 46.865

Recorded: Podsreda, Styria, 1997

Played by: Franc Jercl (harmonica), Anton Švajger (baritone), Franc Jercl (accordion)

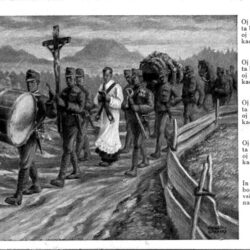

Marches were used as military band music to mark special military and state events. In folk music they came to express their original role; that is, to accompany marching or walking. They were especially played to accompany wedding processions to the church and back, and also often as an accompaniment to the two-step dance.

GNI M 21.789

Recorded: Podkoren, Upper Carniola, 1958

Sung by: Jože Pleš

On the basis of comparison with older transcriptions of this song, it is clear that this song originated with the shortening of the period of military service from fourteen years to eight years; that is, after 1845 (Kumer, 1992: 15, 53). Gradually, along with the shortening of the song, the motif of questioning one’s own fate became the focus. The version of this song in the recording was connected with a drinking song with the same melody, [31] and therefore this questioning is not a tragic one.

GNI M 22.578

Recorded: Podveža, Styria, 1958

Sung by: Mima Ajnik

The ballad “Prošnja umirajočega junaka” (A Dying Hero’s Request) originated in kajkavian Croatian territory and was first known in Slovenia only in Prekmurje and Bela Krajina. It spread to other Slovenian regions during the First World War, and during the Second World War it became established as a song in the Partisan movement (SLP I: 100–119).

GNI DAT 123

Recorded: Artiče, Styria, 2000

Sung by: Franc Jeršič, Tine Lapuh, Jože Molan, Ivan Haler, Drago Bogovič, Štefan Fuks, Ivan Fuks, Tine Pinterič, Jože Štarkl, Slavko Rožman; played by: Jernej Kolar (diatonic accordion)

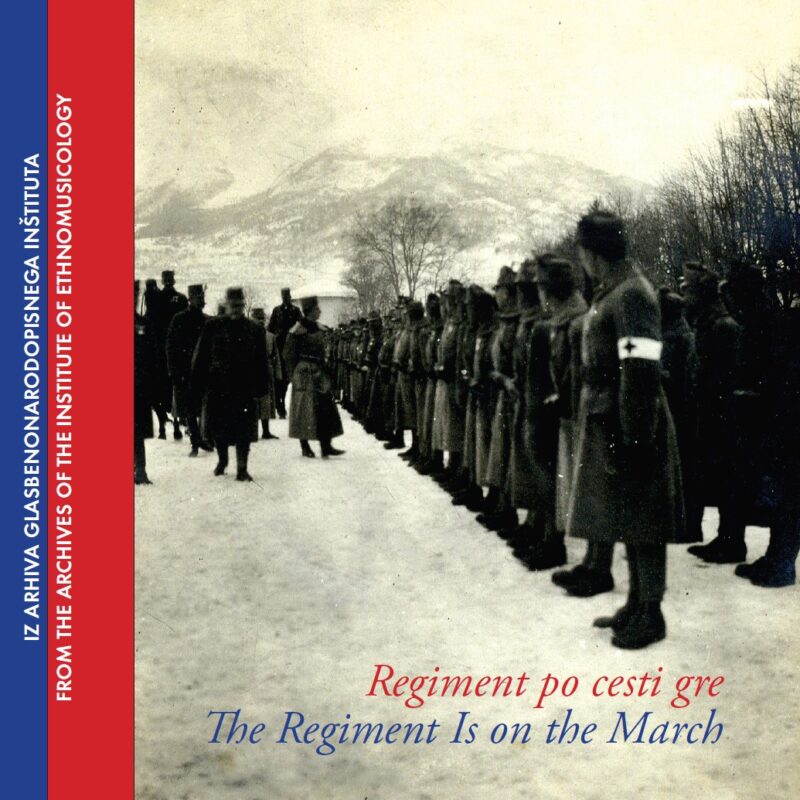

Today the march “Regiment po cesti gre” (The Regiment Is on the March) is one of the best-known traditional Slovenian military songs, and its fate is also interesting. One of its versions mentions the zemlja prajzovska (‘Prussian land’), which indicates that it became part of the heritage of Slovenian military songs circa 1866, during the Austro-Prussian War (Kumer, 1992: 138). Because of its motif of departure, it was classified as a love song in the collection Slovenske narodne pesmi (Štrekelj, 1900–1903: 256–257). Gradually, however, it became more important as a means of encouraging soldiers (Marolt, 1915: 7). It also first appeared in this role during the First World War (Andrejka, 1916: 53).

The spread of this song elsewhere is shown by transcriptions of the song from German-speaking territory, in which the first stanza has the same meaning as in Slovenian. One of these transcriptions states that the first stanza is based on a Slovenian folk song (Baumann, 1939: 24).

Marija Klobčar: The Expressiveness of Traditional Slovenian Military Songs

Traditional Slovenian military songs represent the part of Slovenian folk song creativity whose content is directly tied to wars, preparation for war, military conscription, and its consequences. The images of these songs were determined not only by these circumstances, but also the lives of these songs against the backdrop of wars and all of the events connected with them. It is therefore important to take into account their vitality and changing role in everyday life when interpreting these songs and understanding their variability.

The selection of songs on this audio publication takes both into account: on the one hand, it reveals the traces of war in song as etched into the memory of the nation, and on the other hand it takes into account the reflection of life in them – whether that which was directly connected with wars or preparation for them, or the recollection of wartime events long after the roar of the guns had ceased. It was this life that determined the durability of the traces of these songs among the people.

This audio publication therefore presents not only military songs in the basic sense of the term, but also includes songs that are indirectly connected with these events; that is, songs that the first scholarly edition of Slovenian folk songs partially classified as ballads [1], and partially as love songs. Interwoven with these are instrumental melodies and traditional Slovenian bell chiming. The combination of these songs into a uniform sound memory offers an insight not only into the way that song transforms the image of wars, but also how it is reflected in memory that transcends time.

The Folk Song as a Reflection of Wars and Preparation for War

The most historically recognizable songs on the audio publication are reworkings in song of events that are directly connected with wars or preparations for them. This group also includes the first two ballads – connected with the figures of Adam Ravbar (16th c.) and Gideon Ernst von Laudon (1717–1790) – that reflect the wars with the Turks in song [2]. Namely, the memory of these great military conflicts and victories has endured the longest in the form of ballads. This is only preserved in folk heritage with the midday ringing of the Angelus. [3]

Other songs that directly relate to known military conflicts do not deal with these events in a narrative manner. The basic characteristic in the emergence of these songs was their topicality, which was connected with their fundamental role of emboldening soldiers. [4] Songs of this type, including those that refer to military engagements right up to the 20th century, are most appropriately termed “military songs” with regard to their direct connection with wars and their content.

A comparison of these types of military songs collected in various periods [5] presents an interesting finding: as the events with which they are connected have receded in time, the topicality of these songs has faded as well. Military songs connected to historical events [6] were therefore subjected not only to the general processes of change that are characteristic for folk songs, but were also quickly forgotten by people when they were replaced by more current ones (Krek, 1858: 243, Štrekelj, 1908: 3–4) or were consciously or unconsciously interwoven into new song narratives about wars. [7]

Despite this process, Slovenian folk songs connected with wars and warfare have preserved traces from the oldest periods right up to military engagements in the First World War and even the Second World War. The oldest military songs in today’s sense of the term go back to the time of mercenary armies (Kumerm 1992: 12). Mercenary armies were made possible by the development of firearms and the introduction of trained infantrymen and light cavalry. Mercenary forces already had a constant presence in Slovenia in the second half of the 15th century (Simoniti, 1991: 114–115). Whereas the songs about the conflicts with the Turks preserved the images of heroes, the songs connected with the mercenary armies recall the tricks used to recruit soldiers and they are therefore also tinged with regret. [8] Military songs also retained a number of terms and concepts relating to the everyday lives of soldiers from the time of the mercenary armies, [9] and it is in songs that these have been preserved the longest.

Even though collectors lamented the disappearance of songs about the battles with the Turks during the very first efforts to collect traditional Slovenian military songs (Krek, 1858: 243), in people’s consciousness considerable vitality was maintained through folk song as a memory of the time of universal compulsory military service – that is, the period after 1769, when forced recruitment was introduced, or after 1771, when Empress Maria Theresa defined recruitment districts for all regiments (Švajncer, 1992: 66). This recruitment was characterized by lifetime military service. [10] A large number of songs come from this time, and therefore the opinion prevailed that it was only with universal compulsory military service that military songs truly took root in Slovenia (Čremošnik, 1939: 352). Many songs that were created during this time explicitly or indirectly mention the introduction of “new patents” (Štrekelj, 1900–1903: 249–251, Štrekelj, 1908–1923: 26–53, 91, 153).

Along with apparent equality [11] among people, this era of universal military service introduced an important distinction: this compulsory service meant that as many recruits were collected among potential conscripts as were needed (Kumer, 1992: 14). These circumstances explain the semantic background of numerous folk songs and, on the other hand, the folk songs shed light on the method of selecting recruits, which was based on social stratification (Jelušič et al., 2000: 335).

Among the perils of war and the images of the enemy that pertain to the time of universal compulsory military service, the images of the French stand out in particular. These songs can be understood as testimony to the era, and at the same time the French – like the Turks before them – replaced the enemies in certain older military songs (cf. Kumer, 1992: 17). This relates to two periods that, despite certain other military dangers and conflicts, had the greatest impact on everyday life. The military song connected to the memory of wars was the strongest and the most enduring when it intersected not only with the foundations of individuals’ lives, but also those of the group; that is, existence in one’s own territory.

Military Songs Intertwined with Everyday Life

The images of songs connected with wars and warfare was shaped not only by their role in wars and preparations for war, but also their vividness in everyday life. These songs had various roles during time that were not marked by war. The oldest songs connected with significant military events in which the common people did not participate were preserved as a glorification of these events, primarily the battles with the Turks. These songs became established among the common people in the role of sung narratives and served to pass the time during certain group tasks. They largely preserved this role until the middle of the 19th century, when the first transcribers of Slovenian folk songs succeeded in recording them, and they occasionally persisted even longer, in part due to their publication in school textbooks [12] or songbooks (Ahacel, 1838: 21, Marolt, 1915: 41, Andrejka, 1916: 43).

Whereas the songs connected with the major conflicts with the Turks rapidly disappeared in the mid-19th century, the military songs connected with the experiences of the common people themselves had greater resonance. [13] These songs were fashioned in the constant tension between two extremes, between events connected with the duration of military service, wars, preparations for war, and their direct effects, and with the intimate experiences of the backdrop of these wars, with the relationships that marked life far from the battlefield. For the most part, the connection with military service occurred at the intersection of these two opposing orientations, and sometimes as the depiction in song of one or the other.

Military songs in the rear area, in everyday life, existed not only with the departure of recruits of soldiers to the front, but also enriched everyday life on special occasions after they returned from the battlefields. At first they were sung in places where older and younger men congregated. This was primarily in two environments: in inns and during traditional serenading. With regard to various circumstances and the accompanying climate, these songs differed from one another considerably. The jolly atmosphere of drinking highlighted heroism and pride, often as a memory of success and social life during the time of military service or during war. This suited songs that preserved a heroic, and sometimes fatalistic, memory of war. [14] These songs also retained their character the longest in this environment.

The atmosphere in traditional serenading, in which military songs were also often sung, was the opposite of this; the songs that belonged here were those that would assist the young men in opening the girls’ windows. Songs connected with taking leave of a girl and home, with departures, which were often the only departure for these men and did not promise a return, had great expressiveness. They were also preserved when the circumstances surrounding their creation had already been forgotten and they only retained a message of farewell from one’s beloved. [15] Thus, more than departure for the front or military service, the role of these songs in traditional serenading influenced their vitality.

Serenading kept songs connected with farewells when departing for military service topical and alive, and therefore, of the songs connected with war and warfare, these have remained most numerous and most recognizable. This is demonstrated by written transcriptions and sound recordings, especially those collected in the past decades, [16] at a time when the memory of not only military conflicts, but also traditional serenading, has faded.

The vitality of songs that were originally connected with departure for military service is only one of the reasons that have been completely overlooked so far for the melancholy impression of traditional Slovenian military songs. Leo Hajek (1916), who recorded Austro-Hungarian soldiers’ singing during the First World War, drew attention to another overlooked reason: like other South Slavic nations, the Slovenians prefer to sing after completing their work, while at rest, for which more peaceful ballad-like songs are more suitable (Hajek, 1916).

The melancholy of Slovenian military songs therefore does not signify the cowardice of Slovenian soldiers, but is an expression of the intertwining of customs from everyday life and life in the barracks or at the front. Namely, like at home, for the soldiers singing was an expression of relaxation that followed work performed conscientiously and honorably (Klobčar, 2007).

Traditional Slovenian Military Songs on the Path to Independence

Traditional Slovenian military songs as shaped throughout the centuries are therefore not only a message in song about wars, heroism, and victims, but also perceptible images of the deepest human ties. These images are sketched out in the interweaving of peace and fatal conflicts, in preparations for war, and in the echo of them. In a special way, they also speak in connection with events that received symbolic significance at certain key moments in the development of Slovenian concepts of freedom.

Namely, at moments when freedom and honor were most severely tested, the song carried an important message and, more than this, experience in firmness of character. During times of new distress, Slovenians continually returned to this experience. As Valentin Vodnik wrote in 1809, “Once our forefathers sang, and they slaughtered the Turks; they sang, and ran after Hasan Pasha towards Sisak to drown him in the Sava; and if the Turks broke through to us, they chased them, so that some of the bandits barely escaped. So sing, dear Slovenians, these songs, let song inspire you to heroism, to the defense of our holy empire; and may eternal God assist us!” (Vodnik, 1809: 6). [17]

The military song thus also had symbolic significance at key moments. This was expressed in a special way in the revolutionary year of 1848, when a traditional Slovenian military song with a special expressiveness was taken up by a military band. At that time, they played “first a beautiful march, adapted from a traditional military song: ‘Four came to me / clad in yellow.’” [18] When the band of the national guard unit of Carniola came from Kranj to Ljubljana and played this song, “everyone in Ljubljana was deeply moved;” [19] the people felt “how much power a beautiful folk song has as band music; that is, if it is played by a band and turned into a march, a lively melody, and so on” (Navratil, 1858: 110). [20]

During these difficult times, the folk song inspired courage and hope, and simultaneously these times of great distress also revived old folk songs. These influences were especially surprising during the mobilization at the beginning of the First World War, when “all at once, folk songs were being revived that nobody had heard before.” [21] Therefore the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War’s decision to record soldiers’ singing in the rear areas was also quite significant. These audio recordings, which were made by the Phonogrammarchiv of Vienna, are therefore important to Slovenians not only as recordings of songs, but also as the only direct testimony to the perception of the distress of war expressed through these remnants of sound.

These stresses acquired a new dimension during the Second World War, when the traditional Slovenian military song served to express different understandings of affiliation and freedom, loyalty, and resistance. Various perspectives on ideals encouraged, liberated, and gave purpose to the fighting and its resolution. Understood in this way, the stresses and hopes were maintained until a new era, in which independence was attained in 1991.

This thought also characterizes this audio publication, Regiment po cesti gre / The Regiment Is on the March. Its message is semantically connected with the fate of the song selected for this title: the time of distress and conflict that engendered this song was also capable of overcoming this conflict through song – with a song that traveled not only from soldier to soldier, but from nation to nation as well. [22] And Slovenians used songs to preserve their bearing even when their own sense of nationhood was threatened. [23]

Today, in a time caught between internalization and globalization, Slovenian military songs continue to have resonance among people on special occasions. Here and there they serve as a living or faded memory of successes or of a war that inflicted wounds, but for the most part as its reflection among the people: not only as pride or pain, but as a memory of departure and anticipated reunion – as a memory of friendships that overcame fear; as a clear thought that is something more than the memory of home, a girl, and the field behind the village; as a fading response in song to the ties that are stronger than the roar of guns.

- This audio publication includes heroic ballads; legenday ballads (see Štrekelj, 1895-1898: 628-635) or love ballads (SLIP IV 1998: 380-469) less frequently contained such content.↩︎

- On the audio publication, these are the songs about the Battle of Sisak with its reconstructed beginning Turk če vzel nam Sisek bode (‘If the Turk takes Sisak from us’, no. 3) and the song “Stoji, stoji tam Beli grad” (Belgrade Stands there, no. 4).↩︎

- This bell-ringing was ordered in 1456 by Pope Callixtus III in order to pray for the victory of the Christian army over the Turks at the Battle of Belgrade (Ambrožič, 1993: 27).↩︎

- These characteristics are preserved in the song “Radecki je bil en fajn gospod” (Radetzky was a Fine Gentleman, no. 18), and partially in the song “Naš cesar, naš kralj” (Our Emperor, Our King, no. 21).↩︎

- It is possible to compare the transcriptions that were made at the end of the 19th century (Štrekelj, 1908-1923; GNI ZRC SAZU – SŽ), from 1906 until the First World War (GNI ZRC SAZU – OSNP), i nthe postward period, and in recent years (GNI ZRC SAZU – audio recordings).↩︎

- An example of such a song is “Vojska po polju gre” (The Army Marches through the Fields, no. 14), which directly mentions the vojska francozovska ‘French army’.↩︎

- The ballad “Tam na karpatski gori (There in the Carpathians, no. 25) has the same characteristics, in which adaptation to the circumstances is expressed in the very first verse.↩︎

- The extreme form of trickery in recruitment is connected in folk memory with the purchase of soldiers for the Spanish mercenary army. One detail recalling this recruitment is the mention of yellow uniforms in the song “Prišu je taisti dani” (That Day Has Come, no. 5)(Navratil, 1858: 100, Štrekelj, 1908-1923: 20).↩︎

- These include, for example, the expressions žolnir ‘soldier’, žold ‘military service’, soldat ‘soldier’ (from Ital. soldo ‘soldo’) and others (Kumer: 12-14).↩︎

- Lifelong military service was later shortened: after 1802 it lasted at least ten and up to fourteen years, between 1811 and 1845 a uniform fourteen years, and then was shortened to eight years, and in 1866 to three years (Čremošnik, 1939: 352).↩︎

- Equality was explicitly expressed in the first stanza of the song “Paršle so nove novice” (Fresh News Has Arrived, no. 7).↩︎

- This could explain why there are so many different melodies for the heroic song about Laudon (song no. 4 on the audio publication; SLP I: 92).↩︎

- For example, the first Battle of Custoza in 1848, the Second War of Italian Independence in 1859, and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 were met with broad response (Kumer, 1992: 18).↩︎

- Such an example is the song “Zdaj je pa pršu tisti čas” (And Now the Time Has Come, no. 24); the continuation of the song with the first verse Glažek, glažek rumeni (‘Glass, zellow glass,’ GNI M 21.790) has been identified as the beginning of an independent song – specifically, a drinking song.↩︎

- Štrekelj primarily classified these songs as love songs – from no. 1435 to no. 1701 (Štrekelj, 1900-1903: 201-315). Most characteristic is the song “Sonce je tak nizko sjalo” (The Sun Shone So Low, no. 12).↩︎

- ZRC SAZU, GNI Archive.↩︎

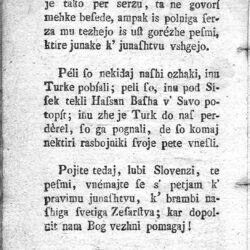

- Original: Peli so naši očaki, inu Turke pobiali; peli so, inu pod Sisek tekli Hasan Baša v Savo potopit; inu če je Turk do nas perderel, so ga pognali, de so komaj nektiri razbojniki svoje pete vnesli. – Pojite sedaj, lubi Slovenci, te pesmi, vnemajte se s petjam k pravimu junaštvu, k brambi našiga svetiga Cesarstva; kar dopolnit na Bog večni pomagaj!↩︎

- Original: pervič prelepo popotnico, narejeno iz imenovane narodne vojaške: Prišli so k meni / štirje rumeni.↩︎

- Original: v Ljubljani ondaj vsi v ognju↩︎

- Original: koliko moč ima lepa narodna pesem v godbi, t.j. ako se prestavi na godbo in se napravi iz nje n.pr. popotnica, poskočnica itd.↩︎

- As reported by teachers from the Savnija Valley to the chairman of the Committee for the Collection of Slovenian Folk Songs (Murko, 1929: 45).↩︎

- Alongside one of the German publications of “Regiment po cesti gre” (The Regiment is on the March) it is stated that the first stanza is taken from a Slovenian folk song (Baumann, 1939: 24).↩︎

- Like many other songs, this title song is also preserved in Venetian Slovenia (Qualizza, 2004: 52) and in Austrian Carinthia (Kumer, 1998: 97).↩︎

- The commentary to songs no. 1, 6, 11, 19, and 23 relies on ethnomusicological observations by Urša Šivic.↩︎

- Valentin Vodnik’s transcription of the song has been preserved (SLP I: 74-75). The lost beginning of this audio recording has been reconstructed on the basis of this transcription.↩︎

- The Spanish mercenaries (the tercios) were a special type of mercenary and from the 1530s onwards were considered the best (Simoniti, 1991: 114). The Austrian army forbade mercenary service for other countries in 1752 under the threat of death (Čremošnik, 1939: 351, Švajncer, 1992: 66).↩︎

- See introduction, pages 23-24.↩︎

- This is a version from Ilirska Bistrica (Štrekelj, 1908-1923: 109-110).↩︎

- In the Prekmurje dialect, the word rumeni (otherwise, ‘yellow’) used here denotes ‘red’.↩︎

- C.f. especially the versions from no. 6744 to no. 6746 (Štrekelj, 1908-1923: 7-8). Štrekelj also cites this song independently (Štrekelj, 1908-1923: 164-169).↩︎

- This is the drinking song “Glažek, glažek rumeni” (Glass, Yellow Glass; GNI M 21.790), recorded as a continuation of this song.↩︎