Slovenian Folk Songs V: Family Ballads

SLP V, 237/5, p. 30

GNI M 24.513

Sung by: Jerica Krajnc (1907); recorded: 1961; Dobec, Notranjsko

This song reflects the unconditional authority of the father. The role of the father is less prominent in family ballads, but he has complete authority over the daughter and can decide whom she marries. This song tells of a girl that inherits property from her mother and cannot part from it, and is also not prepared to enter a convent, so she curses her father. The song also expresses social opposition.

The singer of this version from Inner Carniola learned songs from her uncle, who was a well-known singer and knew many songs. He was likely also a pious man and he may have heard this song during a pilgrimage, perhaps to the Church of St. Primus above Kamnik or to Skaručna. There are also other versions from Upper Carniola (cf. Kumer, 2007, Klobčar, 2007: 31).

239/9, pp. 40–41

GNI M 24.044

Sung by: Neža Glad (1895) and Ana Papič (1902); recorded: 1960; Vas, White Carniola

In this song, the death of a bride before marriage is a punishment because the girl has broken a vow of virginity (to God or the Virgin Mary) or else her mother broke the vow. An angel, the Virgin Mary, or a bird comes to announce the death. Some versions end here, and some continue with the wedding and concealment of the bride’s death. This version includes the motif that the bride is the ninth, like Young Breda (cf. SLP V, type 241). The song is started by the first singer but, because she no longer remembers the words, the fifth stanza onwards is sung by the second singer (cf. Kumer, 2007: 43).

SLP V, 244/8, pp. 79–83

GNI M 25.465

Sung by: Ana Foladore, a.k.a. Kolúćana (1907); recorded: 1962; Osojane/Oseacco, Resia, Italy

This song is one of the most enigmatic (with various erroneous interpretations) of Slovenian folk songs. Because of its poetic reworking in France Prešeren’s “Od Lepe Vide” (Lovely Vida), it has entered the Slovenian cultural horizon as the archetypal ballad, on the basis of which an intertextual series of poetic, prose, and other cultural heritage has been created down to the present day. The core content of “Lovely Vida” is the cunning abduction of a young mother by a pirate. The ballad was completely adopted from the Slovenians by the Gottschee (Sln. Kočevje) Germans, who translated it into their dialect, as shown by transcriptions preserved and recognized by German researchers. To date no ballad completely corresponding to the Slovenian “Lovely Vida” has been found among other nations.

The motif of a cunning abduction appears in the songs of some nations but under different circumstances. Motifs such as the invitation to board the ship, the conversation with the sun and the moon, leaping into the water, and so on are not characteristic of this ballad type alone, although Grafenauer sought to demonstrate something like this when he wanted to determine the “origin, development, and decay” of the ballad “Lovely Vida” (Grafenauer, 1943: 19). Its rhythmic pattern is especially important; in studies by Valens Vodušek (2003) it was been characterized as a trochaic heptameter (4/3) as a “long narrative verse” that Grafenauer considered characteristic for “Lovely Vida.” In actuality, it is a Slavic decasyllabic line composed of two pentameters. The lyrics of the versions of “Lovely Vida” known until then did not follow “sentence stress” but syllabic stress. The Resian versions, which Grafenauer was not familiar with, also have syllabic stress. The ballad “Lovely Vida” has undergone numerous literary treatments all the way from Prešeren’s reworking of it as a poem to contemporary Slovenian poetry, prose, and drama, and it is present in music, the fine arts, and everyday life (cf. Pogačnik, 1988). The majority of literary treatments have been based on the folk song, but Prešeren’s reworking of it as “Od Lepe Vide” (1832) has had a discernable effect. Prešeren chose an elegiac version of the folk song, a transcription by Jožef Rudež, in which he could include a basic yearning motif, a motif of voluntary exile. Derivations of the “Lovely Vida” motif are found in numerous poems (e.g., from Oton Župančič to Veno Taufer), in which the transformation of motifs, semantics, syntax, and other modifications can be observed (Golež Kaučič, 2002: 532–36, Golež Kaučič, 2003: 115–125).

This version from Oseacco/Osoanë in Resia is unusual because at the beginning it mentions the romantic connection between the girl Marjanca (not Vida) and the sailor, their parting, and her marriage to the cobbler and the birth of a son. Marija Klobčar therefore believes that this involves the reunion of the girl with a former lover and also her responsibility to her son, who is ill, and she therefore accepts the “invitation” in which he promises her a remedy for the child and goes with the sailor. However, when she returns the child is dead. Thus the conflict in the song involves the desire to cure the child, not to flee from him; instead, she hopes to save his life with the unknown remedy promised by the “acquaintance.” She does not want to leave her sick child and annoying husband, nor does she long for a better life. Lovely Vida has not left to work abroad; she is an abducted mother that recognizes her error too late. The Resian version from Oseacco/Osoanë therefore contains some new, still undiscovered semantic elements (cf. Kumer, 2007, Klobčar, 2007, Golež Kaučič, 2007, Šivic, 2007 and Matičetov, 1969, 2005).

The musical structure of the Resian versions of “Lovely Vida” is simple, ranking them in the archaic layer of Slovenian musical heritage. The three-note melody of this version also contains characteristically few pitches, and the third varies between minor and major. This version is also especially valuable because it has no true metrical or rhythmic pattern (Vrčon, 1998: 169–178), and the accompanying structure of its stanzas shows great freedom in singing, allowing a style in which it is not possible to speak of a fixed melodic, rhythmic, or metrical base because the singer freely shapes the narrative material (Vrčon, 2007: 86–89).

SLP V, 247/6, pp. 101

GNI M 25.180

Sung by: Ana Leban, a.k.a. Ivancova (1896); recorded: 1962; Poljubinj, Littoral

The reasons for the death of a bride married far away can vary considerably. Versions in which mothers marry off their daughters far from home may conceal social protest against the “purchase” of brides or arranged marriages. In the general folk conception, marriage far away always meant misfortune. Mothers that married off their daughters to strangers from a far-off land for selfish material reasons were subject to especially harsh reproach. Such an unknown future husband could even be a robber or murderer (cf. Terseglav, 2007: 102). This version from Poljubinj in the Littoral shows an interesting treatment of the motif of the death of a woman married far away when she tells the mourners to bury her where soldiers pass and to stretch her hand with her ring out of the grave, so that her lover may recognize it if he should happen to pass by.

SLP V, 248/15, pp. 113–115

GNI M 21.365

Sung by: Marija Šimen, née Sobočan (1912); recorded: 1961; Gornja Bistrica, Prekmurje

The theme of a woman that marries a robber and murderer is Slavic and probably belongs to the common Slavic cultural layer because this material is familiar to all of the Slavic nations in their specific versions. Two thematic versions are known in Slovenian ethnic territory. One primarily appears in central Slovenia, and the other from Styria to the Rába Valley. The core content of the versions from central Slovenia contains the motif of a murderous robber, although the content structure of the versions also overlaps with the theme of a woman married far away. The Prekmurje and Rába Valley versions of the song (“Kata, Katalena”) were influenced by the Croatian, Međimurje, and Zagorje versions of this song type and they rely on the Croatian song about the various fates of three married daughters (cf. Terseglav, 2007, Šivic, 2007: 118–119).

The singer was careless with the lyrics, sometimes mixing them up and repeating certain verses in order to fill out the stanzas, and she omits the ending. From other versions, we know that in the end the robber’s wife dies of sorrow. However, this recording was selected because the melody and singing are so characteristic.

The published version can be found in adaptations for choir and solo performance (Golob, 1980, Krek, 1986, etc.), in 1981 it was sung by a folk-revival group including Mira Omerzel Terlep, Bogdana Herman, and Matija Terlep, and recently it has been popularized in a rock arrangement by the group of the same name, Katalena (Šivic, 2007: 119).

SLP V, 250/1b, p. 122

GNI M 23.990b

Sung by: Marija Marinč and Marija Jakšič; recorded: 1960; Jakšiči, White Carniola

This ballad occupies a special place in Slovenian folk heritage because it is one of the oldest preserved ballads. The material probably came to the Slovenians from the Gottschee Germans because the Slovenian ballad has the same content as the German ballad “Die Geburt im Walde” (The Birth in the Forest), which was first transcribed in the mid-19th century along with three Gottschee versions. The element of King Matthias (Sln. Matjaž) shows that the adaptation likely took place around 1500, unless Matthias is a substitute for some other name. The ballad could not have been created before the 14th century because that was when the Gottschee Germans settled the area, and the German original was created in the 13th or 14th century based on an episode in the Tale of Wolfdietrich (Seemann, 1955). This epic was printed multiple times up to 1600. Its transformation into a ballad must have occurred between 1350 and 1400, when colonists from the Ortenburg estates settled in the Kočevje area; otherwise they would not have been able to bring it with them. The inhabitants of Kostel might have borrowed it from them toward the end of the 14th century at the earliest, and perhaps at the beginning of the 15th century, when the earlier Slovenian settlers and the newcomers to the Kočevje area already had established contact. The ballad is not limited to German song tradition, as shown by examples with more-or-less related in content recorded in Scandinavia, England, and France. The fact that the song is truly old is also confirmed by its form; it is composed in trochaic heptameter with anacrusis, in the characteristic verse form of Slovenian ballads, not in couplets, and the verses repeat only because of the two-part melody. We have selected this two-part melody despite the technical problems at the beginning of the recording (cf. Kumer, 1987, Golež Kaučič, 2007: 122).

252/138, pp. 206–207

GNI M 38.158b

Sung by: group of women; recorded: 1978; Brezen, Styria

The large number of versions of this song (147) indicates that it was one of the most popular and also one of the most widespread ballads. The strong emotion the song contains helped it spread, and the institute’s archive also contains the very latest recordings. Versions of this song range from Venetian Slovenia to the Rába Valley, and from Carinthia to Gorski Kotar. The death of a mother, the consternation of the helpless father, and the forsaken child that is helped by the Virgin Mary are elements that give the song strong emotive breadth. The story itself shocks the listener. Because of the motif of death (in some versions the child also dies), the song used to be appropriate for singing at wakes in the home. The metrical and rhythmical form of the song (octameter and heptameter couplets) allowed melodies to be added and changed (cf. Terseglav, 2007: 216–217). The popularity of the song to the present day is also shown by this version, which is sung by a group of women from Brezen in Styria. The song was first sung by a mixed group but, because their singing was relatively out of tune, we selected this recording of a women’s group for the audio publication. The refrain aj tuj tuja indicates that this is a kind of lullaby for the forsaken child, further heightening the drama and tragedy of the song.

SLP V, 253/9, pp. 224–225

GNI M 38.279

Sung by: Terezija Javornik (1895); recorded: 1978; Paka (Vitanje), Styria

The content of this family ballad shows the basic realization that one cannot trifle with death. Death is the one that chooses, not the parents, because the mother does not wish to surrender her favorite and youngest daughter to death. In this version from Paka, death is represented by suitors, although it then turns out that the rejection of the suitors is the same as death, which then claims all three daughters. Despite its tragic content, this song has a happy refrain and a dynamic melody. The song was likely sung as a wake song and was also composed as such. It probably originates in eastern Slovenia, where the greatest number of farewell songs were created; these were songs composed to commemorate killings and accidental deaths (cf. Golež Kaučič, 2007: 226).

SLP V, 254/23, pp. 243

GNI M 29.942

Sung by: group of men; recorded: 1969; Pirševo, Upper Carniola

The song may have been created based on an actual event because the death of three sons would have likely attracted great attention. It was probably composed by a semi-educated person, a schoolmaster, or an unschooled writer, probably from Styria. Because it was sung at wakes, it can be characterized as a farewell song that was only later transformed into a ballad. The song preserves the memory of long-term military service because the second son was in the military for twelve years. Historical information relates that a law was promulgated in 1771 introducing obligatory lifelong military service. In 1802 this was shortened to ten years for the infantry, twelve years for the cavalry, and fourteen years for the artillery. This was lengthened to fourteen years for all branches from 1811 to 1845, when Emperor Ferdinand shortened military service to eight years, which would put the timeframe for the creation of the song between the end of the 18th century and the middle of the 19th century (cf. Kumer, 1991). The middle son may have been a mercenary soldier that received pay for his service. In this version the first son is a student that studied for twelve years, and the second a soldier that served for twelve years; both of them die in their thirteenth year. The third son lies ill for one year and then dies. This version is very condensed and repeats the characters’ roles (cf. Golež Kaučič, 2007, Marty, 2007: 235).

SLP V, 256 A1/11, pp. 267–268

GNI M 32.826

Sung by: Julija Molnar (1908); recorded: 1970; Kétvölgy/Verica-Ritkarovci, Rába Valley, Hungary

This song comes from the eastern part of Slovenian territory (Styria, Prekmurje, and the Rába Valley) and it is only from here that we have transcriptions; the song has not spread to other parts of Slovenia. The event is set in Hungary, and in one version the setting is Carniola, so it can be concluded that the song also came to the Slovenians from the Hungarians, or via the Croatians, because sometimes (as in this version from the Rába Valley) the well-known Croatian pilgrimage church at Marija Bistrica is mentioned. Perhaps the mention of a foreign town only serves to indicate that the event occurred somewhere far away, in another land. This song belongs to the subtype of the wicked stepmother theme, which is a widespread theme and shows that blood relations were stronger than later legal obligations. This version shows great strophic variation, with couplet, quatrains, and even cinquains, and a moral is appended at the end (Golež Kaučič, 2007: 269–270).

The tonal sequence of this version from the Rába Valley shows the melodic influence of neighboring Hungarian musical heritage (Šivic, 2007: 270).

SLP V, 256 A2/10, pp. 278–279

GNI M 42.360

Sung by: group of men and women; recorded: 1984; Sv. Danijel, Styria

This is a more recent song on the wicked stepmother theme. The event is condensed into a child’s desperate search for his mother, in a dialogue between the dead mother and the child and about the child’s sorrowful fate. The song has been categorized as an independent subtype because it has spread in this particular form throughout eastern Slovenian territory (Styria, Prekmurje, and the Rába Valley) and is not found elsewhere. Thus it may be assumed that it was composed as a farewell song and that it only later became a ballad. This is shown by this example from Styria that still preserves the name of the child (Manica) and the singers’ comment that the song was a dirge. The repetition of the second part of each stanza and the moral at the end are characteristic. If this song is truly a farewell song, its origin could be dated to sometime at the end of the 19th century or beginning of the 20th century (Golež Kaučič, 2007: 280).

A3/39, pp. 318–319

GNI M 28.759

Sung by: Ana Rezec (1913), Helena Vrečko (1915), Terezija Flis (1928), Martin Rezec (1937), Franc Rezec (1917) and Ivan Razburšek (1943); recorded: 1968; Reka, Styria

This song is similar to the previous two subtypes about the stepmother and the orphan, but in this subtype the child laments her cruel treatment at the hands of the wicked stepmother and seeks her mother’s help, who takes her into her final resting place. In Slovenia such a song was generally called “Sirota Jerica” (Jerica the Orphan), as Štrekelj labeled it. Because singers hardly ever sing this song anymore, a similar song that we have labeled as a special subtype is more widespread. This is clearly a more recent song because it is sung in the same way everywhere and there are also no special melodic changes. Based on its fixed form and language, it can therefore be assumed that it was popularized through a printed, literary form. This version from Styria also shows no variation and the last section, partly a refrain, is quite emphatic as in the other versions (Golež Kaučič, 2007, Šivic, 2007: 345).

SLP V, 257/7, pp. 351–352

GNI M 23.987

Sung by: Ana Delač (1900) and Marija Marinč (1899); recorded: 1960; akšiči in the Kostel Valley, White Carniola

The theme of the wicked stepmother and the stepdaughter is known throughout the northern Slavic area, as well as in western Europe, especially in the Scandinavian countries. It is known among the Ukrainians, Czechs, Poles, and Croats. Perhaps it is of artificial origin or even a translation from Czech that was transplanted into Slovenia and that was disseminated through being reprinted in school readers. In this song the stepmother has a distinctly negative role, treating the stepchild especially cruelly. The stereotype of the stepmother has a very clear motivational background because in general a non-biological relationship was weaker than a biological one.

The melody of this example from White Carniola (there are only three audio recordings), which is taken from the dance called the zibenšrit ‘seven-step’, indicates that it is a foreign transplant, as do its language and formal elements. The last stanza is known as a “traveling stanza,” which was able to move from song to song (Golež Kaučič, 2007: 354).

SLP V, 258/12, pp. 359–360

GNI M 28.185

Sung by: Katarina Sušnik, a.k.a. Bolčarjeva teta (1886); recorded: 1967; Krtina, Upper Carniola

This song about a stepmother that is cruel to her stepdaughter in various ways reflects the era before Christianization. The stepdaughter named Saint Christina appears in this song completely by chance because the legends about this saint do not confirm the story. This saint died a martyr’s death under Emperor Diocletian, but the legend of Saint Christina contains nothing to indicate that she had lost her mother. The saint was probably incorporated into the song by chance. Perhaps this song can be viewed as a folk interpretation reflecting the suffering of this saint, which may also be indicated by the punishment of the stepmother (she is carried away by devils) and the assumption of Saint Christina.

The song is certainly medieval. An additional sign of the archaic nature of the song is the old Slavic decasyllabic verse, a characteristic simple, one-part melody, as in this version from Upper Carniola (cf. Kumer, 1968a: 318), and an astrophic arrangement of verses. These are characteristics of examples of the oldest folk-song heritage (Golež Kaučič, 2007: 367).

SLP V, 261 B/2, pp. 375–376

GNI M 32.723

Sung by: Julija Bajzek, née Braunstein (1918); Veronika Ropoš, née Braunstein (1922); Tereza Mižer, née Braunstein (1938) and Ilona Györvary, née Bajzek (1938); recorded: 1970; Felsőszölnök, Rába Valley, Hungary

This Rába Valley version about a forsaken orphan belongs to the group of songs about a dying mother that leaves behind bereft orphans. Because all the versions are from Prekmurje or the Rába Valley, this is probably a song that was created in this area and did not spread across Slovenia. The versions, including their refrains, do not differ significantly from one another. This is probably also the case of a song created based on a real event that was originally sung as a wake song (Golež Kaučič, 2007: 374–378).

SLP V, 263/4, pp. 384–385

GNI M 27.118

Sung by: Marija Tekavec, a.k.a. Skajževa (1896); recorded: 1965; Dane, Lower Carniola

This song belongs to medieval heritage, which is shown by the motif and melody of this version from Lower Carniola. The motif is taken from the feudal period, when feudal lords were allowed to punish unfaithful wives without any legal consequences. The count pushes his wife out the window and this is therefore a legal remnant: defenestration, or removal of an unwanted person by throwing him or her out a window (Vilfan, 1961). The manner of expression and the structure of the versions (including this one) indicates that they were either created by or long preserved among the common people (cf. Terseglav, 2007: 385–386).

SLP V, 267/56, p. 438

GNI M 38.863

Sung by: Pavel Ogris, a.k.a. pri ŠošŹlcŹ (1926); recorded: 1979; Bodental, Carinthia, Austria

The ballad “An Unfaithful Lady with Three Guards” was originally a family ballad. Type A (cf. SLP V/266A, pp. 392–395) preserves the ballad structure, whereas in type B this is already weaker. The ballad form, which deals with adultery and punishment for it, reflects common people’s view of the feudal lords. At the core of the ballad is a social opposition, and at the same time a national one because the majority of the aristocracy were of foreign origin. With its genre reclassification (it is already changing from a narrative song into a lyric one with a truncated plot structure), since the end of the 19th century it very rapidly spread across all of Slovenian territory and the events were transferred from the castle to the village environment. As our informants also state, this is a bachelor’s song, but not a love song.

This version from Austrian Carinthia is sung by a man and has lyrics with strong dialect features. It is already losing its plot structure and is more of a dialogue between the two protagonists. It is a characteristic example of this song, which quickly spread across all of Slovenia and is better known as the ballad with related content “Nezvesta gospa s tremi stražarji” (An Unfaithful Lady with Three Guards, /A; cf. Klobčar, 2007: 443).

SLP V, 273/7, p. 470

GNI M 41.474

Sung by: Jožica Klanjšček; recorded: 1983; San Floriano del Collio, Littoral, Italy

The ballad “A Brother Kills His Sister” sings about incest between a brother and a sister and is known in two forms in Slovenia – as a ballad and as a pantomime dance. This ballad was transcribed in the mid-19th century but it is probably older in origin. In 1909 this song was transcribed in Slovenia in a different genre form, indicating its German origin because according to available information it came to Slovenia from German-speaking territory (cf. Anderluh, 1966) and through school. Teachers that learned this song at training colleges disseminated it in schools as a pantomime so that the taboo motif was hidden in the simple children’s game “Mariechen saß auf einem Stein” (Maria Sat on a Stone) (Ramovš, 1992: 387–388). Before the Second World War it was quite widespread in Slovenia; because the song was spread through school, a large number of versions did not arise. This version from San Floriano del Collio/Števerjan also does not significantly differ, neither in dialect nor in content (cf. Klobčar, 2007, Šivic, 2007: 472).

SLP V, 274/4, pp. 475–476

GNI M 35.929

Sung by: Marija Ravnjak (1931) and Slava Jelenko (1931); recorded: 1976; Stenica, Styria

This song about the killing of a stepfather, which contains the germ of bloody revenge, also belongs to the oldest layer of Slovenian folk songs. The “Orestes motif” can be recognized in it. According to Grafenauer, this motif is believed to have entered European oral tradition from Greece, but it took a somewhat different path to the Slovenians. In the Slovenian versions of the killing of the stepfather, the Orestes motif is almost completely gone, and especially the motif of bloody revenge, which was quite pronounced in South Slavic oral literature (cf. Terseglav, 2007: 476). The ballad of Rošlin and Verjanko was the motif and thematic antecedent for France Prešeren’s narrative poem “Od Rošlina in Verjankota” (Rošlin and Verjanko, 1832) and appears in a number of modern metatexts (cf. Golež Kaučič, 2004: 71– 93, 2007: 477–478).

The singers of this Styrian version probably also used a written source as their basis because it is clear that they sang Prešeren’s version of the song. Although the singers did not know the lyrics well, it is clear how the content of Prešeren’s version was condensed and then became the property of folk singers. The singers thus omitted Preseren’s own text insertions between the dialogues as too artificial, and they focused only on the event. The song was sung at wakes and therefore this function itself preserved the song until today.

SLP V, 277/16, pp. 499–500

GNI M 29.075

Sung by: Anton Leva (1914), Alojzija Leva, née Hren (1914) and Antonija Polanec, née Hren (1911); recorded: 1968; Oplotnica, Štajersko, Styria

categorized as a dirge (Sln. slovo) in origin, a song type especially characteristic of northeast Styria. This song, which was first used for a funeral service or requiem mass (Klobčar, 2002: 7–22), was later sung in memory and as a reminder to later generations. When it lost this function, it was reclassified as a ballad and spread across all of Slovenia. The event that the ballad describes is documented in the registry of deaths in the Parish of Šentlovrenc, when the father of the Dolenšak family in the locality of Mostje shot his sons France and Valentin on 31 January 1875. He was given a life sentence for this crime (Kumer, 1996: 141). The Styrian version is interesting because it preserves several details of the event as well as the name of the murderer (cf. Klobčar, 2007, Kovačič, 2007: 507).

SLP V, 286/120, pp. 647–648

GNI M 27.311

Sung by: Stanko and Pepi Čapelnik (11 and 6 years old); recorded: 1962; Libuče, Carinthia, Austria

The motif of the unwed mother that kills or rejects her child and is punished for it is known in folk-song tradition throughout almost all of Europe. The German folklorist John Meier believes that the Slovenians received this motif from German tradition (from the ballad “Die Rabenmutter” – The Cruel Mother, DVldr. 114), although it seems that the German ballad is from a later period and the Slovenian from an earlier one, and so it arose independently. The motifs of the Slovenian ballad were probably also adopted by the Gottschee Germans. The ballad could have arisen in the transition of society from a matriarchy to a patriarchy. This motif has been used in four ballad forms in Slovenian folk-song heritage. In the first there is an unwed mother that commits her crime premeditatedly so that she can marry as a virgin bride. When her rejected child appears on her wedding day and accuses her of the crime, she is unrepentant and calls upon the aid of heavenly forces to demonstrate her innocence and she is damned. This form has been made into the type presented here. In all of its versions, the ballad of the infanticide bride has a similar core content composed of four parts: in the first the shepherd is herding his flock and finds or meets a child; in the second the child reveals to him that he is his uncle and his mother is the shepherd’s sister; in the third they go together to the wedding, where the child’s mother is getting married as a virgin bride and the child reveals her; and in the fourth the bride is punished and sometimes penitent as well. The lyrical form is almost always a combination of octameter and heptameter: ––/––––/––

distributed across all Slovenian ethnic territory. This means that it is one of the most widespread ballads of all. This recording from Loibach/Libuče is interesting because the lyrics are complete and because it is sung by two children that learned the song at a very young age and reproduce it with nearly no mistakes. This example is also interesting because the children sing it in two parts (cf. also Kumer, 1968b, Golež Kaučič, 2007, Kovačič, 2007: 712–713).

SLP V, 287/68, pp. 760–761

GNI M 29.906

Sung by: group of men, accompanied by violin zither; recorded: 1969; Zagorica (Dobrepolje), Lower Carniola

Material about an infanticide (a bride and a condemned woman) is known throughout Europe, but is handled in various ways. Songs with these kinds of terrible stories were printed on leaflets in Europe and sold. Hence the Slovenian expression nove cajtenge sem bral ‘I was reading new papers’, in the sense of stories on flyers, can also refer to official announcements of executions. Ballads about a condemned infanticide can be categorized into three groups with regard to three different beginnings and later shaping of the lyrics. The first group begins with asking Urška why she is sad, and this is followed by her testimony of infanticide. The second group begins with the introductory formula about nove cajtenge ‘new papers’, from which the young man learns about the sentencing of his girlfriend (e.g., in this recording from Zagorica in Lower Carniola). The form that is known from versions indirectly revealing her fate through the young man’s narrative can be termed the ‘female prisoner’ version, following Vraz (NPI 1839: 82). The third begins with a greeting and reproaches toward the heartless girl (with various names). Examining transcriptions from across Slovenia, it can be seen that the core content of all the songs is the same. Among the versions of the ballad about the convicted infanticide, the developmentally oldest are those that belong to the first group because they are closest to presumed original; that is, the versions from Ihan, Ljubljana, and Mengeš. A series of similarities in the lyrics, mentioning the same female names, the setting (Ljubljana), and the same legal motifs are indicators that the song was probably created based on some real event; specifically, in the first half of the 18th century in Ljubljana because it mentions the town jail at Tranča, where the infanticide was locked up before her sentence was carried out (cf. also Kumer, 1990 and Golež Kaučič, 2007, Kovačič, 2007: 771).

The example of the type “The Convicted Infanticide” also has an exceptionally large number of versions (80). It is represented here by a recording from Lower Carniola and in a version that begins Nekaj novega sem zvedew ‘I’ve found out something new’ and also mentions the “Ljubljana field” – an area formerly known as Friškovec, where criminals were hung. This recording is interesting because the singing is accompanied by an instrument (in this case, a violin zither), which is unusual, and the singing itself is given a somewhat heroic interpretation , which mitigates the terrible and foreboding atmosphere of the ballad and is suitable for concluding this audio publication. This song is sung by a group of men and not women, as would be usual. This once again demonstrates that Slovenian folk singing was sung by multiple voices and not only by women, even though it was primarily women that preserved ballad singing in the past.

Marjetka Golež Kaučič: Family Ballads

Introduction

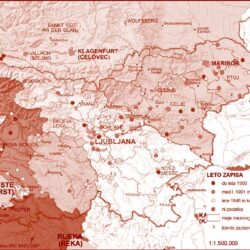

The audio publication accompanying this volume of Slovenske ljudske pjesmi (Slovenian Folk Songs) is not only an audio complement to the volume, but also an independent publication with an extensive foreword and scholarly commentary. The Institute of Ethnomusicology is issuing this audio publication independently, unlike the previous four CDs issued together with RTV Slovenija. It is a compact presentation of family ballads from across all of Slovenian ethnic territory. The volume includes no fewer than 54 types of ballads about the fates of families with 857 versions (as well as 62 versions of Serbian and Croatian songs in Slovenian territory), whereas the audio publication presents only 21 types with 22 audio recordings – that is, all of those for which audio recordings exist. This selection of audio recordings was made in an effort to present the greatest diversity of music and lyrics (part songs; solo singing; men’s, women’s, and children’s voices; special singing styles; various melodies; special features of lyrics, including verse and rhythmic structure; etc.).

The individual audio recordings, which were all made in the field, were also selected based on recording quality or because they represent a priceless historical document despite their technical shortcomings. We tried to present the field recordings as faithfully as possible in preparing the audio material in order to preserve their original documentary value. We have removed or mitigated technical problems in places where this would not affect the material itself in order to facilitate listening. In several places it was not possible to completely remove background noise and technical problems, and so these have been left in, but do not excessively disrupt listening.

This text is summarized in condensed form from that in the volume, and the commentary on the songs was prepared based on the individual audio recordings, presenting them in varying textological and ethnomusicological detail.

The International Framework and Literarization of the Ballad

Family ballads are folk ballads that speak about the fates of families; together with love ballads, they represent a full 34% of all Slovenian folk ballad material. An overview of European ballad collections shows that, in addition to love ballads, family ballads are very frequent. For example, in Lithuanian tradition the family ballad is more or less synonymous with ballad. In addition to original Slovenian motifs, family ballads contain some general European or Slavic themes that connect Slovenians with the cultural space shared with various other European nations. The universality and fundamentality of family relations, the similarity of life stories, and tragic complications and responses to them are similar among very distant nations, but they develop specific features due to different national heritage and the motifs are shaped independently. Certain themes and motifs are thus more or less archetypal (Jung, 1995: 64, 87).

Songs had to contain general human themes, interesting plots, and basic emotions to create a foundation for stories to develop, which is characteristic of the entire European ballad tradition. Individual fates gained a collective character and so they were also able to pass into tradition. Thus it was possible for the Slovenians and Portuguese to thematize adultery in very similar ways; for example, in the Slovenian ballad “Nezvesta gospa s tremi stražarji” (An Unfaithful Lady with Three Guards; song type 266/A) and in the similar Portuguese ballad “Dona Filomena.” To take this even further, the incest motif, which is manifested in Slovenia in the ballad “Brat umori sestro” (A Brother Kills His Sister, 273), is known throughout the Hispanic world (in Mexico, Chile, Cuba, etc.), except that the incestuous relationship is between a father and daughter instead of a brother and sister. This gave rise to one of the best-known ballads, the romancero “Delgadina,” which ended up as one of the intertextual antecedents in Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Memories of My Melancholy Whores (2004). Some Slovenian ballads have also thematized such a strong and basic motif or such a semantically open story that they have become the foundation for several later works of literature. This is especially true of “Lepa Vida” (Lovely Vida), which is one of the best-known “female archetype ballads” (244), appearing in over 50 works of literature. Intertextuality using these ballads is especially frequent in modern Slovenian poetry (e.g., Veno Taufer, Gregor Strniša, Milan Vincetič, etc.; see also Golež Kaučič, 2003).

Family Fates and Conflicts

As a subject of analysis, the structural content of family ballads contains the natural life course that starts a family: the path from courtship to child. The thematics and motifs of family ballads (the feudal and rural environment, the time of the Turkish raids, pilgrimages, etc.) reflect the social and legal regulations of the historical periods that the individual ballads date from. Family ballads present the fates of the people that create relations in the immediate and extended family, and they portray these relationships within the various social and historical frameworks of individual time periods because the family is one of the oldest forms of human association (Zupančič, 1988: 381). Family relations were among the most important relations in people’s lives, and these included blood relations (between individuals and groups) as well as artificial and spiritual relations (e.g., fraternity and godparenthood; Ravnik, 1988: 384). Connected through the wider social structure, in various historical periods these groups had various rules that defined families in the legal sense. Among the well-to-do and especially in the rural strata, the extended family (or “large” family) predominated; from the end of the Middle Ages to modern times, the “small” family in each generation has consisted of the married couple with the master of the household as the bearer of property rights plus male and female servants (Vilfan, 1961: 283). According to Herlihy, the family has played a dual role, and various intellectuals have viewed it as an instrument of repression that enslaves adults and destroys children, whereas others have viewed it as a last refuge (Herlihy, 1995: 113). Thus, as in love songs, one can also most often trace the European template of the woman in family ballads in various relationships to the father, husband, and children. Children, especially girls, were under the supervision and ownership of the parents. The family was a microcosm that depended on the macrostructure of the society that it was part of. Although sometimes different relationships operated in the family than in the broader social environment, for women the role of the family was protective and repressive at the same time. The family primarily represented property, and only after this an emotional environment. Women and men thus had separate roles in the family. The role of the father in family ballads is less represented; however he has, for example, complete authority over the daughter and can determine whom she marries (237). The authority of sons and brothers (i.e., of males) is also very strong. According to Vilfan (1961: 48), in Roman law the only master in the family was the father (the pater familias), but in Slavic law the sons and brothers of the head of the kinship group also had authority. Family and kinship relations are strongly reflected in song, and this primarily in an explicit division between the male and female worlds. There was generally no inheritance through female lineage, and in the Middle Ages this fell under the aegis of a male relative, although women had some say within the family, where they made decisions on affairs connected with protecting and arranging the home, and they also played a major role in decision-making about children. The power of the mother in deciding the daughter’s fate, as well as that of the sons, can be seen in a number of songs (238, 239), and a girl inherited property through her mother (237). The oldest form of concluding a marriage was the purchase and abduction of a bride, which was a contractual form of concluding a marriage that was further concluded by representatives of her kinfolk or tribe with purchase money for the bride (247). A woman that got married left her father’s house and went to her husband’s family. In Slovenian family ballads, the mother has two images: one that is demanding and authoritative toward her children, and one that is suffering for them. This second image is less frequent because in folk songs pragmatics win out over emotional pangs. The mother decides on her children’s marriage; her authority is unconditional and she is responsible for the death of her own daughter (247, 248), but she suffers when she expresses care for her child that she has forsaken after her death, or for her children that she has abandoned to a stepmother (249, 259, 256 A3). It is obvious that the blood or biological relationship is the strongest because the combination of stepmother and stepdaughter, or stepson and stepfather, and so on no longer properly counts as a family; only the mutual obligation to survive applies, but this is not a family in the proper sense. The mother knows that the stepmother has provided for the children poorly, and therefore she entreats or threatens her. From this legal and sociological perspective it is also clear that such an association is primarily negative for orphans (256 A1, A2, 257, 258). A special characteristic of medieval personal law was the concept of specially protected persons (i.e., widows and orphans), and violent acts against such persons were aggregated offenses (Vilfan 1961: 248). Perhaps the orphan was specially protected; nonetheless, folk song always characterizes the orphan as the victim of a wicked stepmother or as a person that always loses out in the family because of the non-blood relationship. Within the family that is created after the mother’s death, the orphan’s fate is maltreatment. The stepmother therefore played a distinctly negative role. The stepmother was always wicked, and even cruel and inhuman (257). For the creators of folk tradition, the stepmother seemed like evil incarnate, one who deserved punishment because of her actions. In these songs this could take a supernatural form (e.g., the stepmother burns in hell) or could follow the principle of retributive justice (258). The folk singer operates at the levels of justice, and therefore, with the destruction of evil, the creator and eventually the listener experience satisfaction.

It can be said that songs primarily reflect the patriarchal family type, in which the head of the family holds power and authority and which is characterized by a strong division between men’s and women’s work. The role of the woman was distinctly subordinate and tied to the male figure; the woman had to be obedient to her husband, not respond to wrongs committed against her, and also suffer her husband’s infidelity. In folk songs the woman is always under some sort of care, both emotional and material. Infidelity or adultery was also a frequent motif, and a wife’s infidelity was usually strictly punished; for example, in types 267 and 268. In addition to the relationship between the wife, husband, and children, the family ballad also thematizes the relations between sisters and brothers; for example, incest (273). The song types about the infanticide bride and the convicted infanticide (286, 287) are especially interesting and have the most versions. These numerous versions thematize child-killing by unwed mothers because in the social structure of the time unwed motherhood resulted in shame and ostracization. According to the moral code of the folk, the only possible penalty for infanticide was death, often delivered by God, but also by secular judges. In both ballads the woman is stigmatized as an unwed mother that rids herself of her child in one way or another. The unwed mother had already been condemned, and therefore she also acted in this manner, often out of despair. Infanticides could be condemned to being buried alive and then having a stake driven through their chests (Dolenc, 1942: 64).

Special Features of the Song Genre and Structure

Some songs on this audio publication are of more recent origin and were probably created from the second half of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century in eastern Styria. These are known as farewell songs (Sln. slovo, pl. slovesa) and were created based on actual accidents or murders, mentioning the person, place, and time involved, as a sort of sung obituary or as songs on leaflets or death notices in song. This type of song was known in England as a broadside ballad, in Germany as a Bänkelsang, and in Bohemia and Moravia as a kramářská píseň. It was only later that they were categorized as narrative songs and thematized the sudden death of daughters or sons, or the murders of sons (253, 254, 277). In these songs the folk singer expressed his horror at the terrible event, graphically described it, praised the deceased, and mentioned the sorrow of surviving relatives (Chessman, 1994, Klobčar, 2002). One can also observe transformations of ballads that simply hide a taboo motif (e.g., incest) in children’s pantomime of the song (273). These songs must be understood as historical testimony and as esthetic messages and, in some manner, as messages from folk singers to those listening to the songs.

The rhythmic structure of the audio recordings indicates that the heptameter (––/––) dominates, and some of the family ballads had characteristic verse forms, such as the common Slavic lyric decasyllabic line (258), trochaic heptameter with anacrusis (250), octameter and heptameter couplets (known as the pilgrimage verse), and hexameter and pentameter couplets (known as the Nibelungen verse). The pilgrimage verse predominates in only three song types with a large number of versions (over 100). These are the types “Vdovec na ženinem grobu” (A Widower at His Wife’s Grave, no. 252), “Nevesta detomorilka” (The Infanticide Bride, no. 286), and “Obsojena detomorilka” (The Convicted Infanticide, no. 287). This means that these songs are of recent origin (cf. also Golež Kaučič and Terseglav, 2007: 19–23).