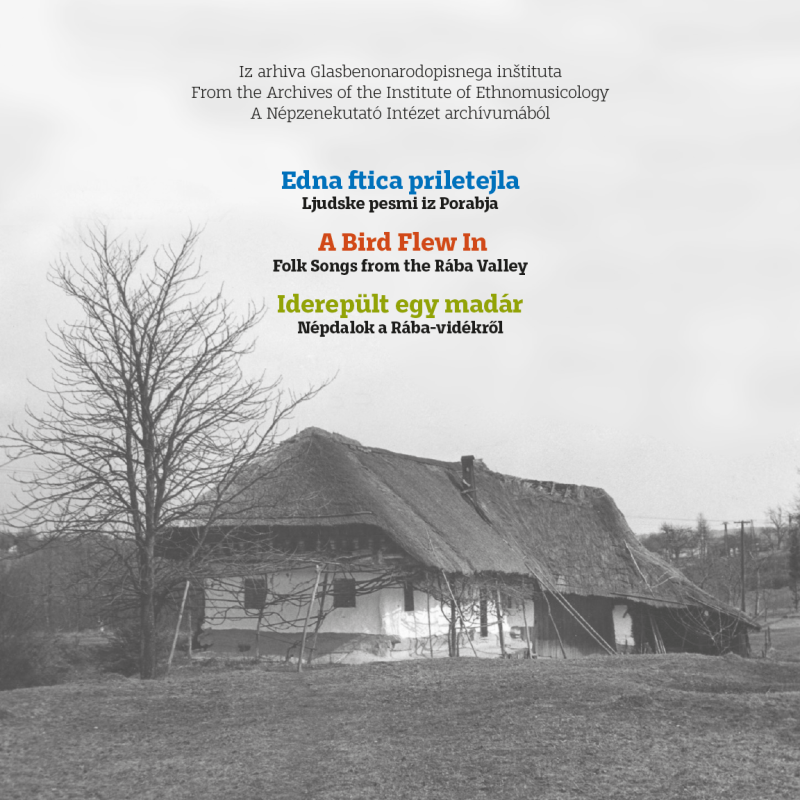

A Bird Flew In: Folk Songs from the Raba Valley

GNI M 31.336

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 4. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

GNI M 32.484

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 11. 11. 1970

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI DAT 110/6

Recorded: Monošter/Szentgotthárd, 26. 1. 2000

Sung by: A. Sukič (*1938), M. Dončec (*1944), M. Korpič (*1944), M. Háklár (*1944), M. Anderko (*1933), M. Svetec (*1949), A. Filip (*1932), M. Lang (*1940), A. Schwarcz (*1939), M. Rituper (*1938)

GNI M 33.596

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 1971

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 33.903

Recorded: Verica/Kétvölgy, 2. 2. 1972

Sung by: M. Gašpar (*1951)

GNI M 32.653

Recorded: Sakalovci/Szakonyfalu, 13. 11. 1970

Sung by: M. Gredlič (*1921), E. Šerfec (*1930), J. Takács (*1927)

GNI M 33.488

Recorded: Slovenska ves/Rábatótfalu, 28. 1. 1971

Sung by: M. Melcer (*1904)

GNI M 34.237

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 6. 3. 1970

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 32.781

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 12. 11. 1970

Sung by: K. Dončec (*1918)

GNI M 31.479

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

GNI M 33.594

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 1971

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 31.705

Recorded: Andovci/Orfalu, 7. 3. 1970

Performed by: E. Mešič (*1956)

GNI T 261-A/12

Recorded: Verica/Kétvölgy, 6. 3. 1970

Told by: F. Merkli (*1958)

GNI M 32.636

Recorded: Sakalovci/Szakonyfalu, 13. 11. 1970

Played by: I. Makoš (*1934) – diatonic accordion (fude), J. Horváth (*1939) – violin (gosli)

GNI M 31.464

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

GNI M 32.673

Recorded: Sakalovci/Szakonyfalu, 13. 11. 1970

Told by: J. Gredlič (*1954)

GNI M 34.028

Recorded: Verica/Kétvölgy, 5. 2. 1972

Sung by: A. Borovnjak (*1913)

GNI M 32.545

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 12. 11. 1970

Sung by: V. Gašpar (*1940)

GNI M 34.229

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 4. 3. 1970

Told by: J. Labric (*1919)

GNI M 34.230

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 4. 3. 1970

Told by: J. Labric (*1919)

GNI M 34.231

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 4. 3. 1970

Told by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 33.462

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 27. 1. 1971

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 31.573

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 6. 3. 1970

Sung by: L. Šulič (*1946), F. Labric (*1936), I. Dravec (*1944), J. Labric (*1941)

GNI M 33.593

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 1971

Sung by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI T 667/5

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

S. n.

GNI M 33.515

Recorded: Sakalovci/Szakonyfalu, 28. 1. 1971

Sung by: E. Šerfec (*1930), J. Takács (*1927), M. Gredlič (*1921), E. Németh (*1939), J. Nemeš (*1911), M. Cserkuti (*1921), H. Čuk (*1913)

GNI M 31.547

Recorded: Verica/Kétvölgy, 6. 3. 1970

Told by: A. Borovnjak (*1913)

GNI M 32.726

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 15. 11. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), T. Mižer (*1934), V. Ropoš (*1922)

GNI M 34.232

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

Told by: F. Labric (*1914)

GNI M 31.561

Recorded: Verica/Kétvölgy, 6. 3. 1970

Told by: F. Merkli (*1958)

GNI M 31.340

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 4. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

GNI M 32.782/2

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 12. 11. 1970

Told by: K. Dončec (*1918)

GNI M 31.460

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

GNI M 31.701

Recorded: Andovci/Orfalu, 7. 3. 1970

Sung by: M. Mešič (*1898)

GNI M 32.789

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 12. 11. 1970

Sung by: K. Dončec (*1918)

GNI DAT 110/1

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 26. 1. 2000

Sung by: M. Bartakovič (*1942), I. Terplan (*1932), M. Merkli (*1944), A. Unti (*1926), M. Dončec (*1948), A. Nyírő (*1941), E. Karba (*1953), M. Rituper (*1938)

GNI M 33.483

Recorded: Slovenska ves/Rábatótfalu, 28. 1. 1971

Sung by: M. Melcer (*1904)

GNI M 32.588

Recorded: Sakalovci/Szakonyfalu, 11. 11. 1970

Sung by: J. Šraj (*1902)

GNI M 32.780/1

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 12. 11. 1970

Sung by: K. Dončec (*1918)

GNI M 32.780/2

Recorded: Števanovci/Apátistvánfalva, 12. 11. 1970

Sung by: K. Dončec (*1918)

GNI M 32.745

Recorded: Slovenska ves/Rábatótfalu, 16. 11. 1970

Sung by: M. Korpič (*1907)

GNI M 31.472

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, 5. 3. 1970

Sung by: J. Bajzek (*1918), I. Győrvári (*1938), A. Šulič (*1912)

Marija Klobčar: Songs from a Region That Knew How to Listen to Birds

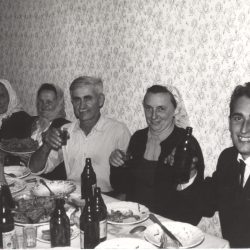

In 1970, half a century after the Yugoslav-Hungarian border divided easternmost Slovenian ethnic territory (cf. Hirnök Munda 2004), a group of researchers at the Ljubljana Institute of Ethnomusicology set out on a fieldtrip to the Rába Valley and the Slovenians living there. The purpose of the trip was to improve the body of knowledge on Slovenian folk creativity by making audio recordings in the Rába Valley, with the awareness that the audio character of this region also needed to be preserved in this way. At this time, the Yugoslav-Hungarian tensions behind the Iron Curtain had eased; the control at the border was less strict, and the 1972 Hungarian constitution included a clear provision on ethnic rights (Kozar-Mukič, 1984: 8).

The Institute of Ethnomusicology thus recorded the song tradition in the Rába Valley while the local culture there was still exceptionally alive due to isolation, but at the same time was facing some changes. In this, the institute researchers’ interest in the songs of the Rába Valley Slovenians at least partly transcended the typical attitude of Yugoslav Slovenia towards the Slovenian spoken in the Rába Valley. The Rába Valley dialect, which gained practical and symbolic importance mainly through its use in liturgical texts (Just, 2015: 104), was not part of Slovenian instruction in schools; this maintained its linguistic distance from standard Slovenian and made the Rába Valley Slovenians feel that their dialect was inferior (cf. Just, 2015: 103). Interest in the song tradition of the Rába Valley Slovenians therefore also gave symbolic value to the singers’ dialect and recognition to their efforts to preserve their language.

The diverse wealth of songs captured on tape by the institute’s researchers revealed a strong affinity with the Prekmurje tradition, reflecting historical relatedness and subordination to the Hungarian crown, which the Slovenians in the Rába Valley primarily associated with the role of Vas County and, at the end of the nineteenth century, also with the Szentgotthárd area (cf. Kozar-Mukič, 1988: 87). In what had been a single area, this closeness was still preserved for several decades after the Treaty of Trianon that is, after this part of Prekmurje was awarded to Hungary. However, strained relations after the Second World War prevented further interconnections between the traditions (Kozar-Mukič & Hirnök Munda, 2004).

In addition, the material recorded reflects the interconnections both in the songs that the Rába Valley Slovenians borrowed from central Slovenia and in the songs they became familiar with during seasonal work (cf. Kozar, 1996: 140–141); at the same time, they also reflect their coexistence with the Hungarians and Burgenland Croatians of Vas County.

The song tradition of Slovenians living in the Rába Valley presented on this audio publication can only be understood by contextualizing it within the conceptual world that the researchers’ interest examined. In their narratives, which were also occasionally tape-recorded, the singers still preserved the memory of many customs in which archaic elements can be identified. While keeping vigil over the body of the deceased, the character of one-eyed Pestjan, who carried away the deceased, sprang to life with singing, and fairies and mermaids lived in the narratives. The songs and narratives about singing and dancing revealed beliefs preserved in rituals, such as the meaning of water, fire, and flowers at crucial moments of the year or an individual’s life, and the magical importance of songs and dances was also visible in many customs. The narratives therefore also brought back to life the images of the times long gone: from the parish fair in May and the “birch twigs” somewhere “in a clearing,” which people danced around, to minor everyday habits verbalized in the words “Prlé so návado meli …” (Once they used to …).

The wealth of song tradition of the Slovenians living in the Rába Valley reveals a surprisingly strong connection with nature. This connection seems to preserve traces of the development of villages in the Rába Valley: at the end of the twelfth century this area belonged to the Cistercian Abbey in Szentgotthárd and was a wooded, swampy, and sparsely populated territory before that; with deforestation and by draining the swamps (cf. Kozar-Mukič, 1988: 101), it offered many more contacts with nature than farming later on. With regard to expressing closeness with nature, the connection with the motif of a bird is the most surprising: various songs, such as love songs, ballads, and military songs – which, however, are not included on this audio publication – begin with or touch upon the thought of a bird that brought a “joyful message.” Birds are used as metaphors when referring to a beloved person or as an expression of longing, and imitations of birdsong even passed into children’s song tradition. This audio publication also combines its narrative on the song tradition of the Rába Valley Slovenians with notions about birds.

The limited options for presenting this song tradition on an audio publication dictated the selection of songs, which cannot reveal all of the dimensions of the wealth of songs of the Rába Valley Slovenians. The songs were selected based on various criteria, and their versatile expressiveness serves to present the role of singing and songs as comprehensively as possible, and to also reveal the documentary nature of the tradition that testifies to past everyday life in this region along the Rába River.

The audio publication combines both the life path of an individual and the role of the community. Both are also connected with church holidays and harsh everyday life, which barely afforded the luxury of a holiday at all. An individual’s journey is indicated through songs that reveal human destiny torn between love and death, between longing and the cruel everyday life, and between freedom (usually characterized by being single) and dependence (which was especially a result of marriage for women).

The introductory songs on this audio publication, which begins with the song expressively named “Edna ftica priletejla” (A Bird Flew In), are connected with love; these include the well-known songs “Micka vu püngradi raužce bere” (Micka Is Picking Flowers in the Orchard) and “Teče mi voda po ciglaj” (Water Runs over My Bricks), which thanks to their power of longing were also performed in central Slovenia soon after the First World War, as well as the songs “Fantič mi gre v zeleni log” (My Boyfriend Is Going into the Green Grove), “Dekličice, noričice” (Little Girls, Silly Girls), and “Pravo sem ti dostakrat” (I’ve Told You Many a Time), which place love within the framework of the moral limitations in the society of that time. A wedding, which agreed with or went against the individual’s choices, was an important personal and social event filled with rich rituals. On this audio publication, a wedding is illustrated in the songs “O zdaj, moja obseda” (Oh, Now My Wedding Guests), in which the bride bids goodbye to her wedding table, the humorous song “Gospaud je poslo toga medveda” (The Master Has Sent This Bear), composed as a riddle, and the drinking song “Primi, bratec, kupico” (Have a Cup, Brother), the melody of which matches the previous ritual song. However, many love relations could not end in marriage, neither in traditional society nor in modern times, which is also reflected in the song “Moj rauzmarin se doj posüšo” (My Rosemary Has Dried Up); this song also shows foreign influences introduced from central Slovenia.

The harsh everyday life that often started after the wedding is presented in the song “Lajnsko leto sam se oženo” (I Got Married Last Year). This song also shows influences from central Slovenia, just like the song “Mati betežujejo” (The Mother Is Sick): it displays images of cruel destinies, which were transmitted as exciting stories through song even between regions that were far away from one another. In addition to these two songs, the audio publication features the song images of ritually enriched everyday life. Cackling (kokodakanje) is presented, which young men in the Rába Valley used to bring blessings early in the morning for St. Lucy’s Day while kneeling on a piece of wood; New Year’s good wishes in “Frištji bojte, zdravi bojte” (Be Fresh, Be Healthy), and the instrumental carol “Marš” (The March) with the melody from the Hungarian operetta “Három tavasz” (Three Springs), which was played together with good wishes during New Year’s caroling. The Protestant spirit can be sensed in the Epiphany carol “O sveti tri krali” (Oh, Three Kings), which concludes with a request for a gift. A ballad with a medieval tradition about sinning and repenting “Teči, teči, bistra voda” (Run, Run, Swift Water) enters these spiritual horizons, followed by the medieval Easter song “Kristuš nam je od mrtvih stau” (Christ Is Risen from the Dead for Us).

The sounds of the everyday simplicity of child play are presented in three songs imitating the birds: “Gibice bi peko” (I’d Like to Bake Flatbread), “Večerjo sem sküjo” (I Made Dinner), and “Moj oča birauf” (My Father, the Judge); the word birauf in the last one retains the memory of folk law and folk judges. The songs “Šetala se v püngradi divojka” (She Was Strolling in the Orchard) and “O kako je duga, duga paut” (Oh, the Way Is So, So Long) present two opposing responses to encountering foreignness, which was also evident in seasonal work: the first song responds to these encounters lightly and also uses borrowed German words, whereas the other expresses bitter separation from home. The family ballad “Mati betežujejo” already mentioned above is followed by songs that reflect the power of the Christian tradition: the prayer “O Jezoš, ne ostavi me” (Oh, Jesus, Leave Me Not), the pilgrimage song “Mati Kristošova” (The Mother of Christ), and the folk passion “Sveti božji križ” (The Holy Cross), which indicates the frequent use of apocryphal prayers in the tradition of Slovenians living in the Rába Valley.

The military song “Fanti sinički na vojske so šli” (The Szölnök Lads Have Joined the Army) is followed by various responses to everyday life: imitating a cart, ridiculing other villages (in this case Kétvölgy because of the supposed resemblance of its Slovenian name, Ritkarovci, to rit ‘ass’), expressing one’s sense of community in the song “Mi, Senčarje, mi se ne prodamo” (We People from Szölnök Won’t Sell Ourselves), and the humorous counting rhyme “Stari ded, stara baba” (Old Man, Old Woman). This light view of the world is contrasted by the song “Franciška najjakša deklina je bla” (Franciška Was the Prettiest Girl), whose story about a tragic death resembles Styrian dirges, the prayers “Oče naš” (Our Father) and “Zdrava bojdi, Marija” (Hail Mary), and the dirge “Stari ino mladi” (The Old and the Young).

Various motifs from everyday life are also featured in the last part of the audio publication, where songs borrowed from elsewhere predominate: the love songs “Na brejgi trnina” (The Blackthorn on the Hill), “Včera večer sem jaz pismo daubo” (Last Night I Received a Letter), in which the bitter images of unrequited love spring to life, and the song “Na kraj na pajasli” (At the End of the Village), which is also known in Hungarian as “Dombon van a házam” (My House Is on the Hill). These songs also include the humorous song “Moram iti k mojoj kumi” (I Have to Go See My Godmother), which was also popular because it was published in traditional wedding guides, and borrowing from central Slovenia is illustrated by the song “Hodmo na Štajersko” (Let’s Go to Styria). The audio publication concludes with the motif of longing, also illustrated with the migration of birds to the south: the song “Drügački život je lep” (A Friend’s Life Is Good), which preserves the memory of carrying out group seasonal work with the Burgenland Croatians from Vas County, is also an expression of hope.

Based on the song material recorded in the Rába Valley, a songbook was published in 1989 before the collapse of communism in Slovenia and Hungary. Its aim was to help “Rába Valley folk singing continue in younger generations” (Terseglav, 1989: 5). In the years following the collapse of communism, two songbooks with “the richest heritage” were also published among the Rába Valley Slovenians themselves (Mukič & Mukič, 2001, 2003). Today these songs, the majority of which were recorded nearly half a century ago, ring out again. Rába Valley Slovenian is no longer stigmatized, but social conditions and assimilation have severely narrowed its living range of use. With its mission symbolically illustrated by its title “Edna ftica priletejla”, this audio publication comes as an invitation: an invitation to listen and an invitation to sing, and especially an invitation to rediscover the sound narrative about the melodiousness of Slovenian as spoken in the villages of the Rába Valley.

Urša Šivic: The Resonance of Songs and Singing in the Rába Valley

Musical analysis of documentary audio recordings from Slovenia’s Prekmurje region and Hungary’s neighboring Rába Valley consolidates the belief that, although the two regions belong to two different countries, in their expressive essence they are strongly interconnected: this interconnection is seen not only to the west, where both regions are connected by Slovenian, but also to the east, where music in particular is the bearer of many intercultural ties (see also Šivic, 2010).

In Prekmurje audio material, attachment to the neighboring Hungarian environment appears to be a somewhat distant feature, whereas the audio material recorded among the Rába Valley Slovenians reveals quite strong ties to Hungarian music. The “characteristic rhythm of Slovak and Hungarian folk songs” and syncopated rhythm (Dravec, 1957: xxxviii) are still rare in Prekmurje song variants, whereas songs on this audio publication such as “O zdaj, moja obseda” (Oh, Now My Wedding Guests) and “Moram iti k mojoj kumi” (I Have to Go See My Godmother), demonstrate their common use across the border. Considering the frequency of songs such as “Stari ino mladi” (The Old and the Young), “Moram iti k mojoj kumi,” and “Včera večer sem jaz pismo daubo” (Last Night I Received a Letter), their common use in cultural coexistence may also be ascribed to the use of minor scales. Unison singing by two or more singers is an element that, judging from the archival material, continues to be relatively rare in Prekmurje, whereas it is fairly common in Rába Valley material (cf. Kumer, 1975: 101; Dravec, 1957: xlv). Unison singing – which would have been foreign to Alpine auditory aesthetics, which considered it to reflect a lack of singing skill – appears to be aesthetically completely satisfactory in the songs “Pravo sem ti dostakrat” (I’ve Told You Many a Time) and “Mati Kristošova” (The Mother of Christ), both presented here.

Two-part singing in parallel thirds is the basic style of group singing in Prekmurje and the Rába Valley, even in cases when women and men sing together (i.e., with an added bass voice). In this case, the basic structures with voices called na staròu / na staró / nízko (‘old’ or ‘low’ for the lower voice) and na mladòu / na mladó / na vísiko (‘young’ or ‘high’ for the higher voice; cf. Dravec, 1957: xliv; Kumer, 1975: 102–103) are accompanied by a third voice as an octave-lower parallel to one of the voices above. Such voices are then referred to as na staró (‘old’ for the lower voice), na srêjdno (‘middle’ for the middle voice), and na mladó / na vísiko (‘young’ or ‘high’ for the higher voice), in which singers perceive the combination of these voices as three-part harmony. Consistent two-part harmonies in thirds or sixths are common within the predominantly two-part singing, as for example in the song “Micka vu püngradi raužce bere” (Micka Is Picking Flowers in the Orchard), “O kako je duga, duga paut” (Oh, the Way Is So, So Long), and “Drügački život je lep” (A Friend’s Life Is Good). However, with its tonal movement of the lower voice it often shows tendencies to create a momentary bass effect in songs “Edna ftica priletejla” (A Bird Flew In), “Moj rauzmarin se doj posüšo” (My Rosemary Has Dried Up), “Fanti sinički na vojske so šli” (The Szölnök Lads Have Joined the Army), “Franciška najjakša deklina je bla” (Franciška Was the Prettiest Girl), “O sveti tri krali” (Oh, Three Kings), “Mi, Senčarje, mi se ne prodamo” (We People From Szölnök Won’t Sell Ourselves), and “Na brejgi trnina” (The Blackthorn on the Hill).

The singing culture of the Rába Valley presented on the audio publication Edna ftica priletejla is not comprehensive: the recordings were made in an extremely short time, over the course of three years. Audio information for the period from the 1970s onwards is missing; during this time, major economic, political, and cultural changes occurred in the area, which also affected the singing practices and repertoires. Beyond this chronological gray area, recordings from as late as 2000 can be found in our archives; during this time, the gap in “spontaneous singing practice” was filled by revitalizing activities of organized vocal ensembles, both in the Rába Valley and Slovenia. Thus two recordings of women’s vocal ensembles from Szentgotthárd and Apátistvánfalva have also been included on the audio publication as a reflection of the still living memory of the singing on the one hand, and of the necessary unification of lyrics, style, and expression on the other. The songs “Micka vu püngradi” and “Na brejgi trnina” exemplify the typical two-part harmony and short codas of the verses, which are a special feature of Rába Valley singing, and are especially well emphasized here.

Every song on the audio publication Edna ftica priletejla thus portrays the interconnections between the area’s western and eastern musical expression in its own way. By presenting the song heritage of the Rába Valley, it adds to the folk songs documented in Prekmurje – released in 2010 on the audio publication Spejvaj nama, Katica (Sing To Us, Katie) and reveals interconnections that extend beyond national borders and time.