Bell Chiming

T 782/1,2

Col/Littoral

Recorded: Col, 13. 7. 1975

Chimers: Marjan Peljhan 1963, Anton Podobnik 1961, Bogdan Žejen 1963

T 829/7,8

Dolina pri Trstu/Littoral

Recorded: Boršt, 19. 4. 1976

Chimers: Sregij Glavina 1941, Josip Lovriha 1908, Angel Lovriha 1921

T 830/4

Bazovica pri Trstu/Littoral

Recorded: Boršt, 19. 4. 1976

Chimers: Vinko Fonda 1931, Karlo Grgič 1933, Anton Kalc 1931-1980

T 1354/3

Vrtojba/Littoral Karst

Recorded: Crngrob 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Roman Arčon 1938, Jožef Nemec 1930, Peter Štakul 1929

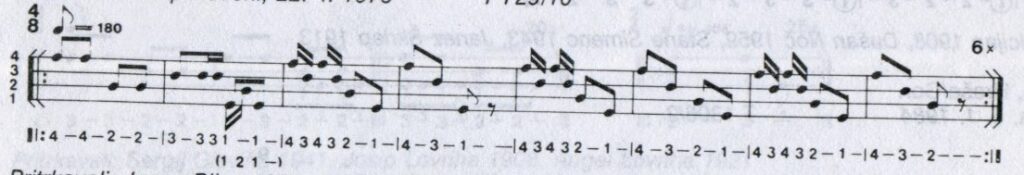

T 1355/3,4

Mengeš/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Crngrob, 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Alojz Belcijan 1908, Dušan Noč 1959, Stane Šimenc 1943, Janez Škrlep 1913

T 1306/2

Hraše/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Šmarna gora, 5. 1. 1984

Chimers: Andrej Bonča 1940, Franc Bonča 1952, Ivan Bonča 1939, Marko Kumer 1964, Jože Zupan 1949

T 898/8

Grad/Prekmurje

Recorded: Grad, 16. 4. 1977

Chimers: Vilijem Žilavec 1906-1977

T 1114/7

Šmihel nad Mozirjem/Styria

Recorded: Šmihel nad Mozirjem, 11. 10. 1981

Chimers: Anton Acman 1963, Janez Goličnik 1961, Martin Goličnik 1962

T 1114/6

Šmihel nad Mozirjem/Styria

Recorded: Šmihel nad Mozirjem, 11. 10. 1981

Chimers: Janez Goličnik 1961, Martin Goličnik 1962

T 729/10

Šentvid pri Stični/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šentvid pri Stični, 22. 4. 1973

Chimers: Janez Bijec 1931, Janec Bijec 1954, Andrej Vencelj 1946, Anton Vencelj 1945

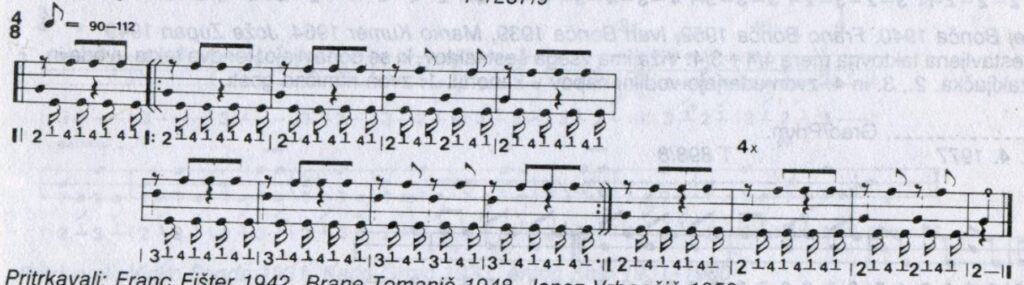

T 1287/9

Brezovica/Inner Carniola

Recorded: Crngrob, 24. 7. 1983

Chimers: Franc Fišter 1942, Brane Tomanič 1948, Janez Vrbančič 1958

T 729/6

Šentvid pri Stični/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šentvid pri Stični, 22. 4. 1973

Chimers: Janez Bijec 1931, Janec Bijec 1954, Andrej Vencelj 1946, Anton Vencelj 1945

T 1354/7

Žabnica/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Crngrob, 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Rajko Bernik 1956, Milan Jelovčan 1965, Jure Kalan 1964, Franci Šifrer 1956

T 899/1

Žiri/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Žiri, 2. 6. 1977

Chimers: Martin Eniko 1949, Viktor Eniko 1911, Vinko Eniko 1941, Jože Primožič 1906

T 1353/6

Brestanica/Styria

Recorded: Crngrob, 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Janko Gabrič 1956, Franc Lekše 1921

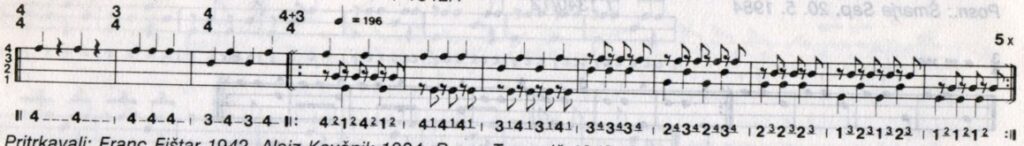

T 1328/8, 10,9

Dob/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Strmec, 9. 5. 1984

Chimers: Andrej Jereb 1967 (a, c), Alojz Limonij (a, c), Peter Vidmar 1935 (a, b, c)

T 1342/1

Račna pri Grosupljem/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šmarje Sap, 20. 5. 1984

Chimers: Franc Mehle 1945, Ciril Zajc 1942

T 1353/13

Vipava/Littoral

Recorded: Crngrob, 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Slavko Božič 1971, Marko Česen 1965, Jurij Fajdiga 1965, Aleš Kodelja 196, Janko Rodnam 1966, Damijan Tomažič 1964

T 1340/12

Polica/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šmarje Sap, 20. 5. 1984

Chimers: Marja Kastelic 1959, Ludvik Kokole 1953, Anton Ogrinc 1937, Vinko Skubic 1939, Matevž Vidic 1959

T 829/5

Boljunec pri Trstu/Littoral

Recorded: Boršt, 19. 4. 1976

Chimers: Danilo Germani 1929, Maurizio Germani 1967, Ivan Zobec 1902, Ivan Zobec 1934.

T 631/1,2

Zgornje Gorje/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Zgornje Gorje, 19. 4. 1968

Chimers: Janez Jan 1898, Lorenc Jan 1890

T 1342/1

Brezovica/Inner Carniola

Recorded: Šmarje Sap, 20. 5. 1984

Chimers: Franc Fištar 1942, Alojz Kavčnik 1934, Brane Tomanič 1948, Janez Vrbančič 1958

T 631/1,2

Cerklje/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Cerklje, 14. 4. 1968

Chimers: Ivan Basej 1935, Peter Novak 1933, Franc Stenovec 1935, Martin Štern 1919

T 1306/1

Hraše/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Šmarna gora, 5. 1. 1984

Chimers: Franc Bonča 1952, Marko Kumer 1964, Jože Zupan 1949

T 898/14

Grad/Prekmurje

Recorded: Grad (Prekmurje), 16. 4. 1977.

Chimer: Vilijem Žilavec 1906-1977

T 1114/6

Radeguna nad Mozirjem/Styria

Recorded: Radegunda nad Mozirjem, 11. 10. 1981

Chimers: Tone Mikek 1940, Janez Raztočnik 1904

T 729/7

Šentvid pri Stični/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šentvid pri Stični, 22. 4. 1973

Chimers: Andrej Vencelj 1946, Anton Vencelj 1945

T 1284/13

Goče/Littoral

Recorded: Budanje, 17. 7. 1983

Chimers: Jože Furlan 1941, Franc Jerončič 1927, Ivan Volk 1946, Stanko Volk 1950

T 898/5

Žiri/Upper Carniola-Inner Carniola

Recorded: Žiri, 2. 6. 1977

Chimers: Martin Eniko 1949, Vitko Eniko 1911, Viktor Eniko 1941, Jože Primožič 1906.

T 1342/2

Višnja Gora/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šmarje Sap, 20. 5. 1984

Chimer: Viktor Mesojednik 1922

T 898/7

Žiri/Upper Carniola-Inner Carniola

Recorded: Žiri, 2. 6. 1977

Chimers: Martin Eniko 1949, Vitko Eniko 1911, Viktor Eniko 1941, Jože Primožič 1906.

T 839/2

Pungert/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Pungert, 16. 6. 1976

Chimers: Anton Markelj 1914-1980, Jože Markelj 1967

T 1115/14

Šmihel nad Mozirjem/Styria

Recorded: Šmihel nad Mozirjem, 11. 10. 1981

Chimers: Anton Acman 1963, Janez Goličnik 1961, Martin Goličnik 1962

T 1352/12

Brestanica/Styria

Recorded: Crngrob, 22. 7. 1984

Chimers: Janko Gabrič 1956, Franc Leške 1921

T 1327/3

Brestanica/Styria

Recorded: Strmec, 9. 5. 1984

Chimers: Janko Gabrič 1956, Franc Leške 1921

T 1342/1

Grosuplje/Lower Carniola

Recorded: Šmarje Sap, 20. 5. 1984

Chimers: Janez Brodnik 1945, Avgust Burgar 1939, Franc Skubic 1944, Peter Vidic 1944

T 638/4

Komenda/Upper Carniola

Recorded: Komenda, 26. 5. 1968

Chimers: Anton Burnik 1928, Andrej Kočar 1939, Franc Plevel 1938, Franc Repnik 1934, Joža Repnik 1940

Julijan Strajnar: Bell Chiming

The producer of gramophone records Helidon (a branch firm of the publishing house Obzorja of Maribor), is proud to present its first audio publication, featuring original folk music from the Slovenian ethnic territory. This unique audio publication is result of the cooperation with the Folk Music Section of the Slovenian Etnographic Institute of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. We wish to introduce the local bell chiming tradition, recorded by the staff of our Section (Igor Cvetko; Mirko Ramovš; Julijan Strajnar; Marko Terseglav, Valens Vodušek) in 1968-1985 (Uher 4000 Report-L, Nagra III B, Nagra IV-stereo). After 17 years of fieldwork, more than 700 chiming tunes were recorded in some 45 localities. Due to limited space, we have had to confine our selection to 37 examples from 26 localities. The choice has been guided by the desire to give the listener some idea of the musical range and variety of our bell chiming tunes.

Bell chiming tunes can be defined as “bell tunes” – rhythmic peals of a number of bells in a certain sequence in order to produce a melody. The essential difference between Slovenian-style chiming (pritrkavanje) and the version generally known outside the Slovenian ethnic territory (calied carillion in English and French, Glockenspiel in German, kolokolnie zvony in Russian) consists in the fact that our chimers (as a rule, one per bell) produce the tunes by directly striking the clapper against the circumference ot the bell. It is a group performance, making use of ordinary bells in any belfry. Carillion, on the other hand (known, tor instance, in Switzerland, France, Belgium, England, North ltaly, the Soviet Union, etc.), is a one-man performance on a set of bells specially arranged and tuned tor this purpose, rung with the aid of machinery, usually including a manual. In short, Slovenian-style chimers (pritrkovalci) are true folk artists, while carillion players are professional or semi-professional musicians, playing either adaptations of compositions for other instruments or original compositions specially intended for this instrument.

The generally accepted technical term tor Slovenian-style chiming is pritrkavanje, though there are numerous local terms in the various regions. In Upper Carniola the alternative expressions are potrkavanje, nabiranje, priudarjanje, klenkanje; in Lower Carniola, klenkanje, potrkavanje; in the White March, klenkanje, linganje; in lnner Carniola also pinkanje; in the Coastal Region, natolkavanje, toklanje, tenklanje, trankanje, kantkanje, klempananje, klepetanje, kompelanje, etc.; in Slovenian Venetia also tamburanje, škomponotanje, mortelanje; in the Resia Valiey, klotananje, tintinanje; in Styria, prtrkavanje, trijančanje, trojančanje, v klenk zvonenje; in the Raba Valiey, klonkanje, klonckanje; in Carinthia, nabijanje, prtrkavanje, zgone bijejo, s pengelnom pobijajo, etc. Various derivations of these terms are used to designate Slovenian-style chimers, e. g. pritrkovalec, potrkač, nabijavc, tenklar, klenkaš, tonkaš, etc.

The peals of bells have always had a number of functions in everyday life; they invite to divine service, strike the hour, warn of fire and other calamities, announce the death of a local, or even try to dispel a hailstorm, etc. Slovenians have always shown a special affection for bells and bell chiming: the sound of a bell is commonly compared to a human voice, and vice versa. In the past (for instance, during World War 1) the locals often secretly removed bells from the belfries and hid them in the ground to prevent the enemy from refounding them into cannons. History does not record a single betrayal of the hiding-place of a bell! Every village is proud ot its bells and bell-ringers, and claims they are the finest in the country.

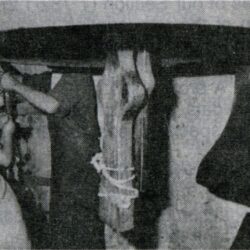

Slovenian-style bell chiming (pritrkavanje) is a folk art typical of the entire ethnic territory, except tor the Slovenian-speaking villages of Austrian Carinthia; but even there the older villagers remember the habit and the local expressions connected with it. It is impossible to establish the origins of Slovenian-style chiming. Reliable sources testify to its popularity in the 19th century; but the custom can be probably dated back to the 16th century. Further research may disclose more details. There is a substantial difference between normal bell-ringing and chiming. A bell-ringer sounds the bell by pulling a rope (in modern times this is often done with an electric motor). A pritrkovalec, on the other hand, climbs the belfry, accompanied by his colleagues, and strikes the clapper by hand against the edge of the bell; since the clapper tends to be heavy, the hand is often assisted by some kind of gadget: the bell may be propped up by poles, or the clapper might be attached to the edge of the bell by a chain or a cord, etc. (cf. our images). Various local terms are used to designate the clapper, of bell’s tongue: kembelj (standard Slovenian), knebelj (Styria), žvenkelj, štremfelj (Lower Carniola), žvenku, rigel (Coastal Region), kladivo, betica (Triestine Karst), jezik (Slovenian Venetia), etc. In some regions, especialiy in Styria, the accepted method is to strike the outside of the bell with a mallet (called kladiv or kij in Styria, tukci in Slovenian Venetia).

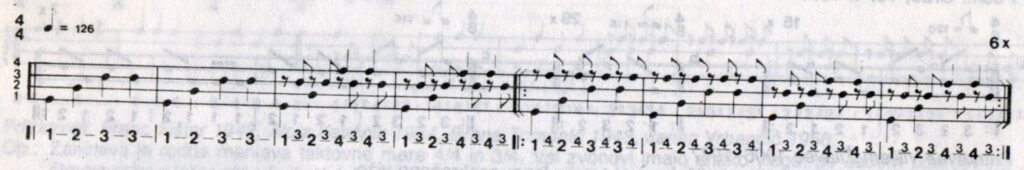

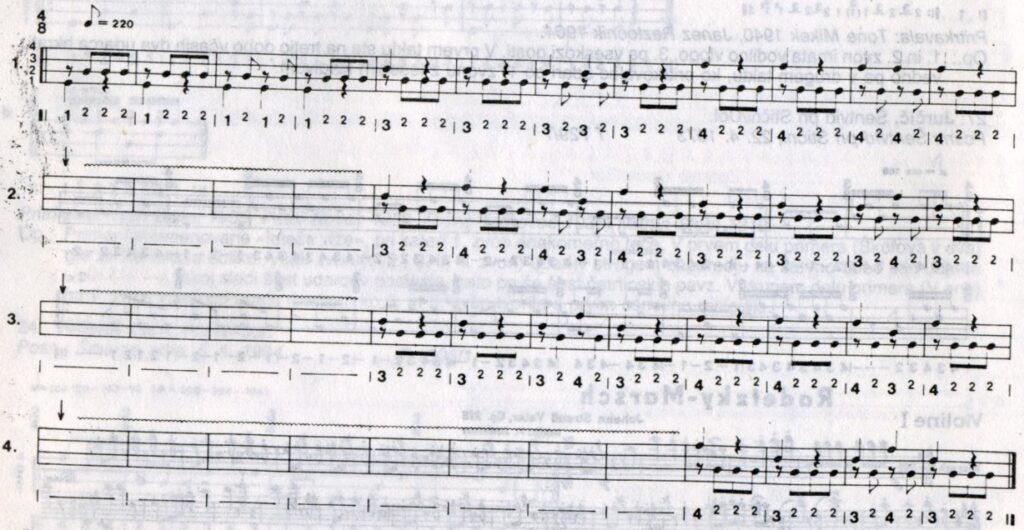

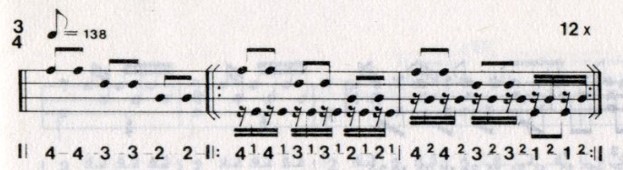

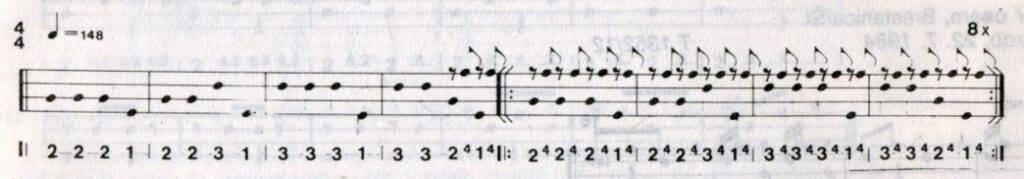

The chime tunes are called viža, štiklc, štuki, komad, etc. The principal strokes, which produce the basic melody, are called žvak, štih (Upper Carniola). The “response” strokes, which compose the tune in interplay with the principal strokes, are called odbivanje or obiranje, while the strokes merely adding to and embroidering on the melodic pattern are calied gostenje or glestenje (Coastal Region), drobljenje, drobit or drobnat. Depending on the method of interplay, chime tunes can be roughly divided into two groups:

1. AII the bells play an equal role, and their successive strokes produce an “unembroidered” melody (cf. our examples 7, 10, 16, 17, 19, 24, 25).

2. Some ot the bells play the basic melodic pattern (consisting of principal strokes and “response” strokes), while one of the bells plays the “embroidery”. There are two subdivisions of this group:

a) “Flying tunes” (leteče viže), where one of the bells (said to be “flying”) is rung with a cord, producing the basic rhythm, while the remaining bells are struck by hand (5, 23, 37).

b) “Standing tunes” (stoječe viže), where ali the bells are struck by hand. This is, in fact, regular practice.

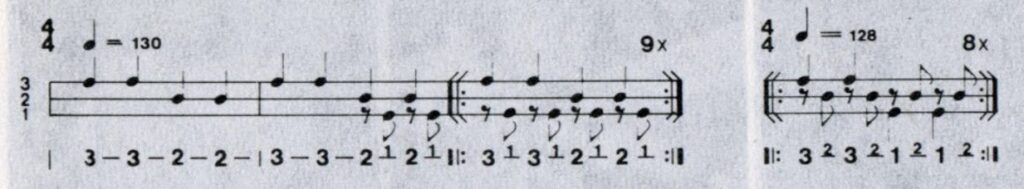

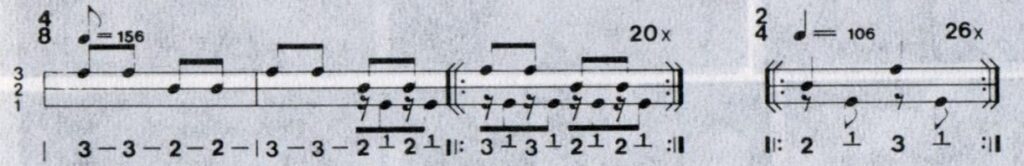

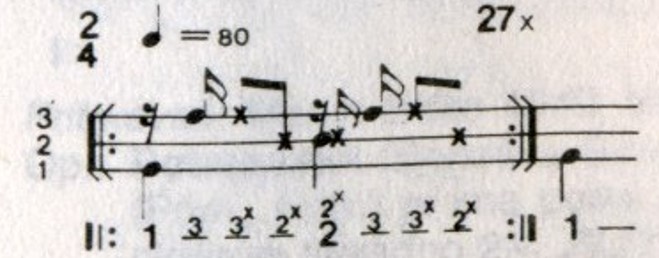

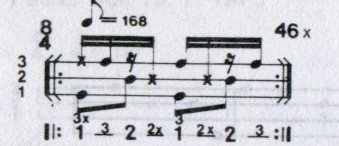

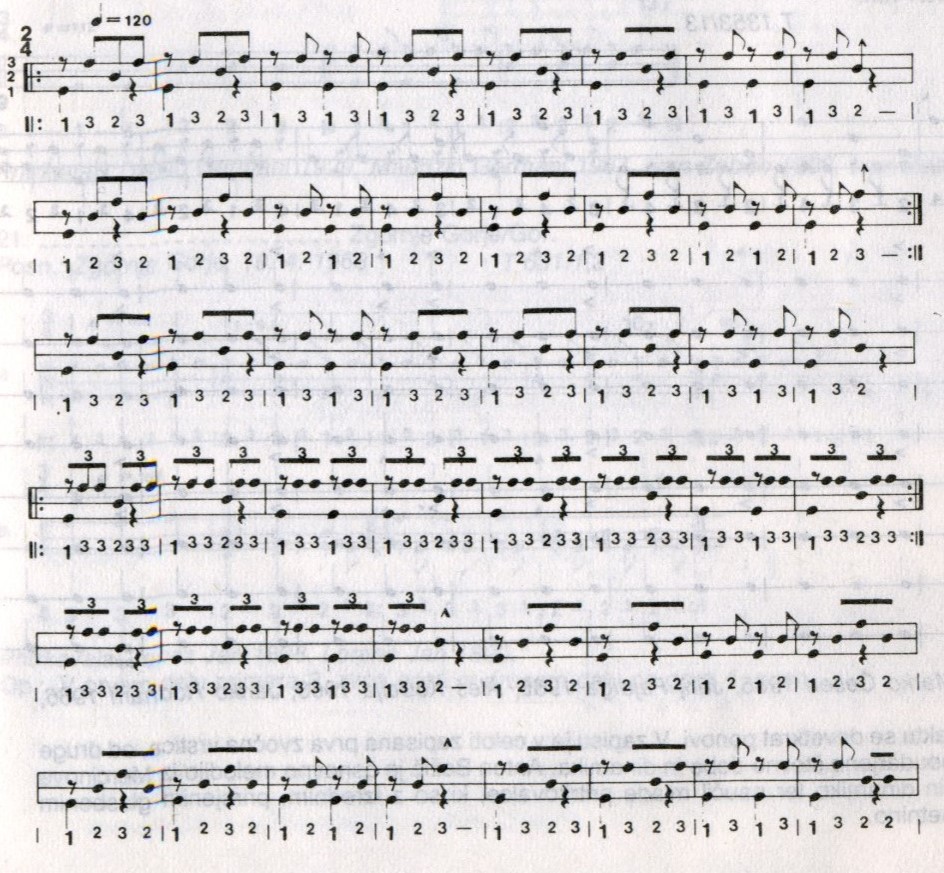

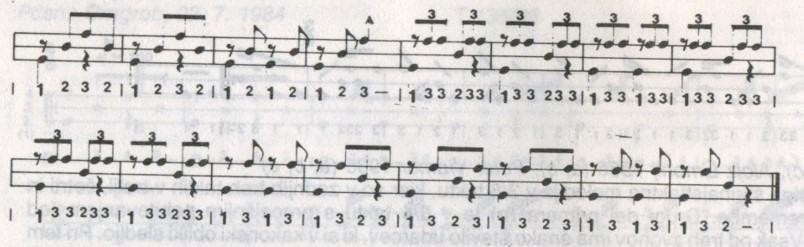

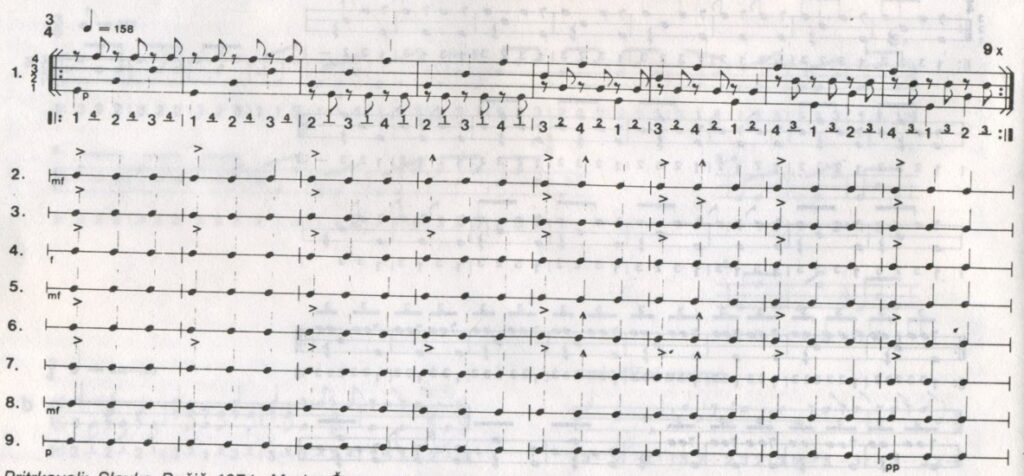

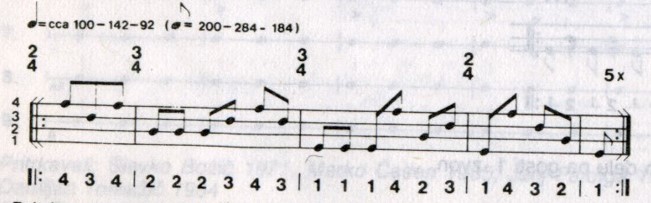

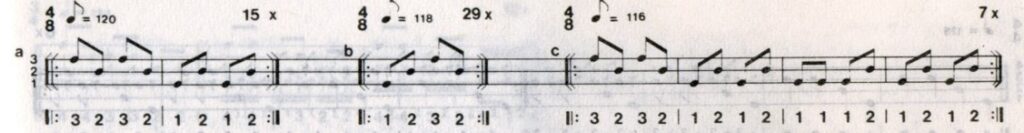

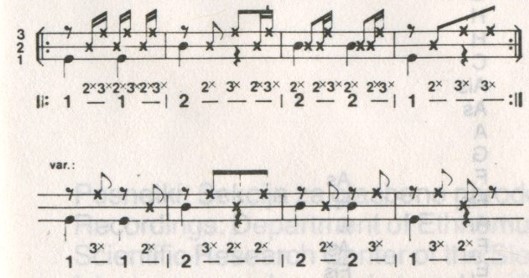

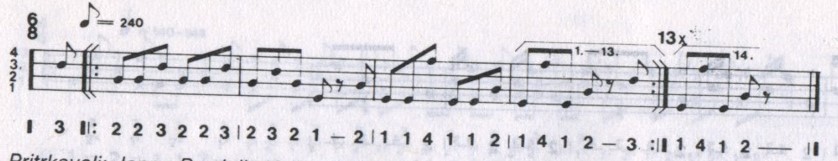

An unwritten law of Slovenian-style chiming says that two bells must never be struck at the same tirne. If this happens inadvertently, the general opinion is that the performance is a flop. Only in some regions (Styria, the Triestine Karst, etc.) exceptions are permitted if the musical pattern demands it (3, 8, 9). The variety of the tunes depends on the number of bells available. The range of melodic patterns can be further increased by the use of mallets. In Marsin (Slovenian Venetia) the clappers are exceptionally long, and designed to be struck in two fashions: either by clapping the tip ot the bell-tongue against the edge of the bell, or the root of the bell-tongue against the upper section of the bell. The two distinctive sounds produced in this way add to the variety of the tune. The quality of the performance depends on the talent, skill and musical ear of the bell-ringers. Often the performers are past-masters of their art, and can distinguish and remember a wide repertory of melodies. Some of them have invented their of systems of musical notation. Anton Božič of Vipava, for instance, uses the following system:

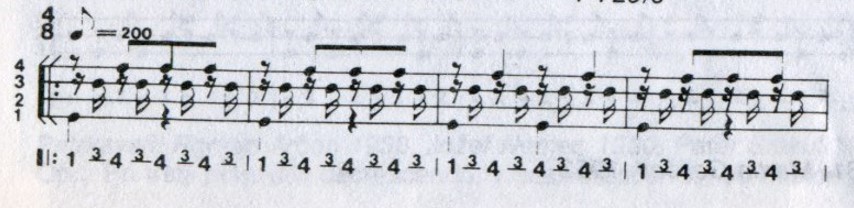

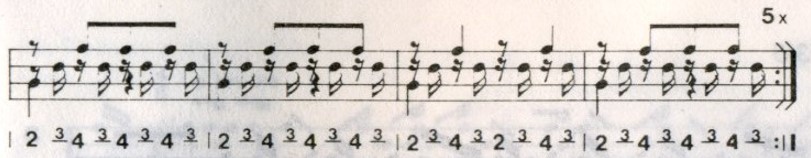

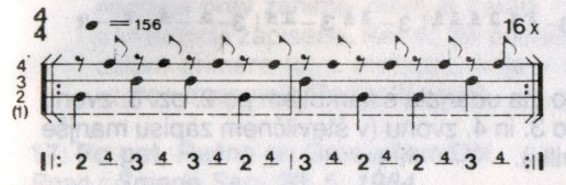

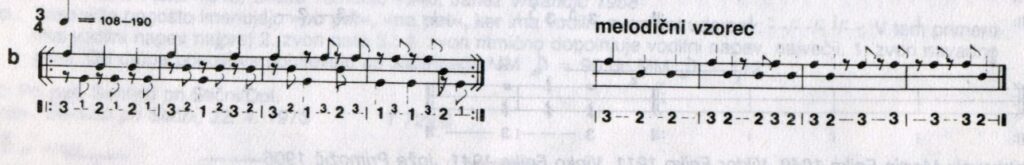

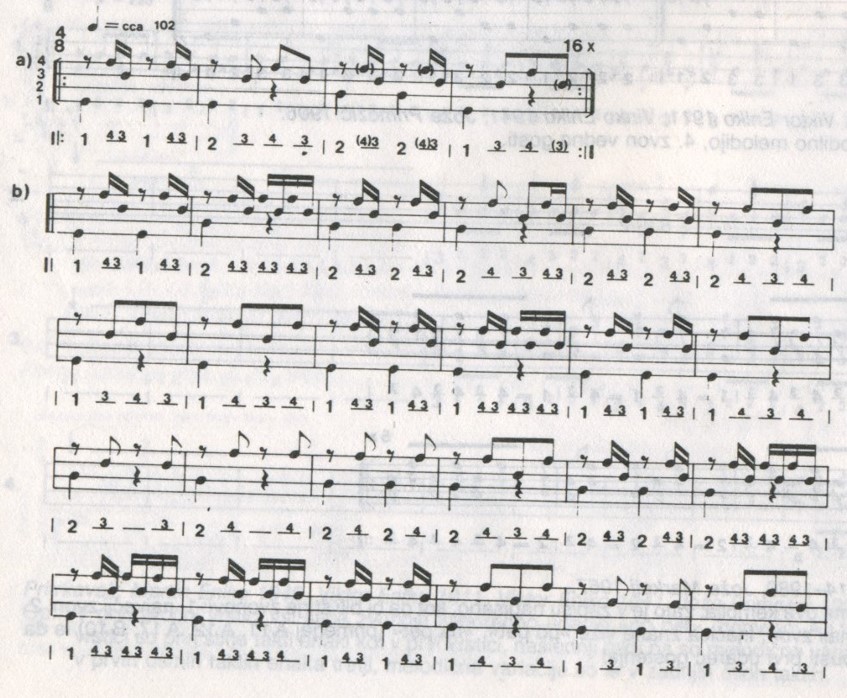

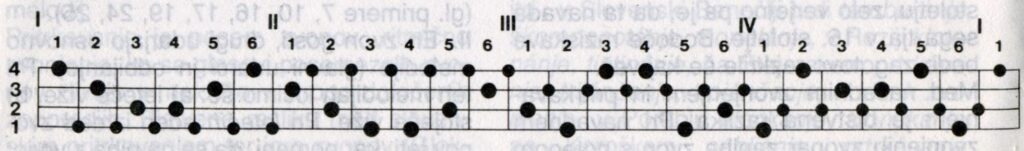

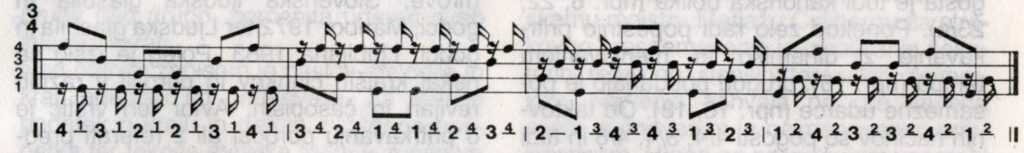

He uses a red dot to designate the fourth bell (first line trom top), a grey dot tor the third bell (second line), a black dot for the second bell, and a blue dot for the first bell (third and fourth lines). Roman numerals divide the tune into four sections, of which each consists of fix units (marked by consecutive Arabic numerals). The principal strokes are marked by dots placed under the corresponding Arabic numeral, while the “embroidery” is indicated by dots placed on the intermediate vertical lines. In a more conventional way, the same tune could be recorded as follows:

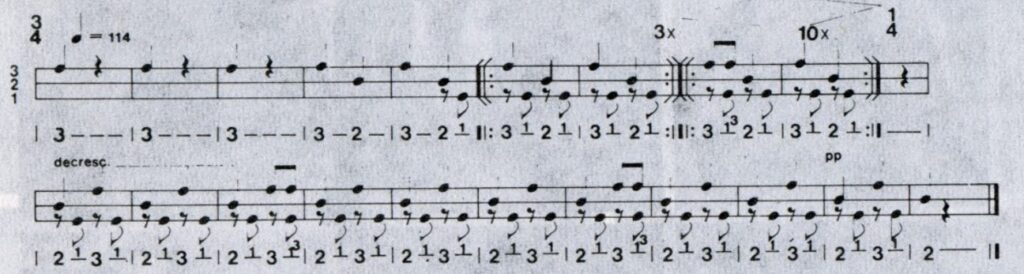

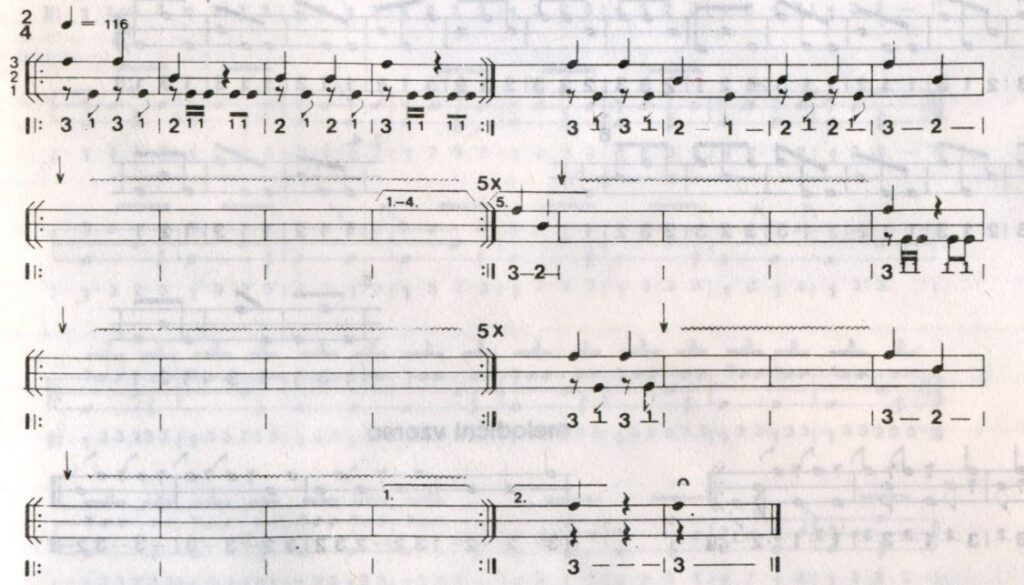

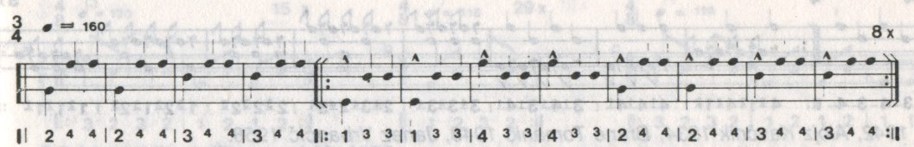

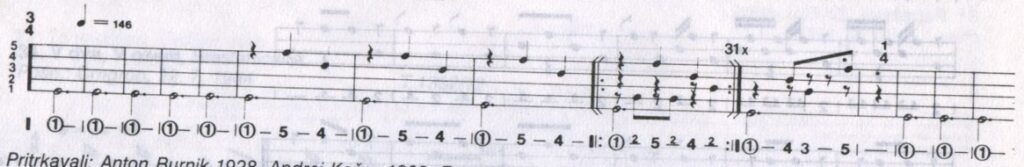

Franc Bonča of Hraše near Smlednik uses vair-coloured geometric figures: a circle for the fourth bell, a rhombus tor the third bell, a rectangle tor the second bell, and a square for the first bell. In his notation (here reproduced in black and white) the “Evening Bell” tune of our item 24 can be recorded as follows:

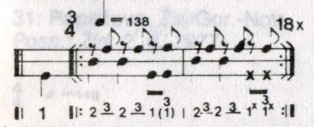

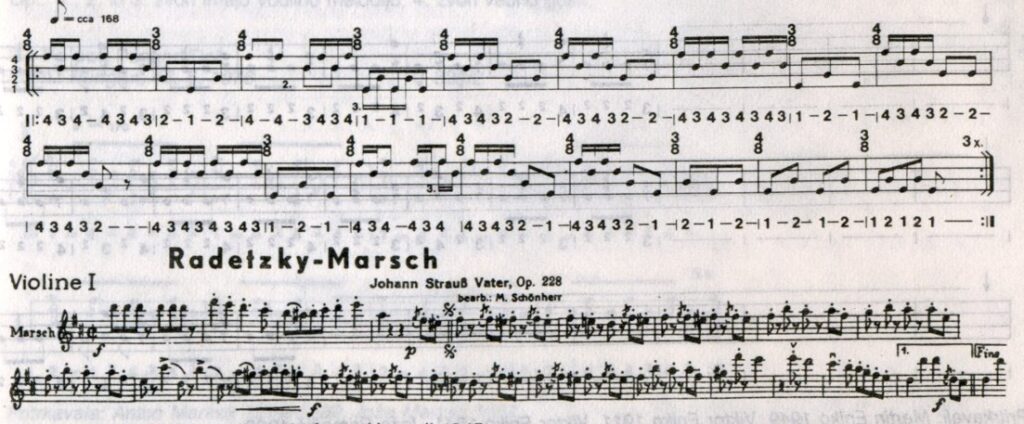

![]()

The performers are usually men or boys (or exceptionally, in more recent times, girls) who have learnt this folk art either in the local belfry, under the guidance of older practitioners, or at home, by practicing on a suspended scythe, a set of cow bells, etc. Just like folk songs, the art of chiming is handed down from generation to generation, and there are famous families or groups of performers. The tunes, too, are transmitted from generation to generation. Some of them are named after their rhythmical patterns, e.g. v eno, v dva, v pet, po pet (17), ta gosta v pet, navadna sedem (6), v osem (34), v enajst (15), etc.; others are called after place names, e.g. Vipavska, Vrhpoljska, Šmihevška, Barnaška, Zagrebška, Radegunšek (33), Komendska, etc., or after a folk composer, e.g. Božončkova, Kovačeva, Luigi Kampanon, Kahnetov (30), etc.; occasionally a tune is named after a folk dance, e.g. štajeriš, špicpolka, polka, osem marš, potresavka (14). Some ot the tunes have quaint names, such as “Getaway Hag” (bejšbaba), (36), “Old Hag” (stara baba), “Pope’s Tune” (papeževa, 31 ), “Bosnian’s Tune (Bosanc), “The Last Fad” (ta nova), “The Fig”, (figa), “The Spinster” (samica), “Bishop’s Tune” (škofova), “Slow Dormouse” and “Quick Dormouse” (počasen polh, 8, and hiter polh, 9), “Evening Bell” (večerni zvon, 24), etc. Over the last five years, a tune called Radecki marš or simply Radecki (16/c) has gained wide popularity; it is adapted trom the well-known Radetzky March by J. Strauss (1804-1849).

The melodic patterns of chiming tunes range from simple one-beat tunes (e.g. 1, 2) to complex, highly inventive compositions (e.g. 16/a, b). The “canon” pattern is fairly frequent (6, 22, 23/a). In some regions the rhythm is diversified by dynamics and speed changes (e.g. 4, 30), while in others the stresses are fairly uniform (16, 18). The most frequent times are 4/4, 3/4, 4/8, and sometimes 6/8 (36); occasionally there are complex rhythmic structures, such as 4/4 + 3/4 (6, 22) or 3/4 + 2/4 (24), or even more intricate combinations (27). The performers enjoy their art, therefore they do not spare any efforts to perfect it. They can practise for hours on end. Usually, chiming makes a profound impact both on practicioners and listeners. Performances take place on major religious holidays, on the occasion of church fairs, confirmation, first mass, etc. Since World War II, they also celebrate New Year’s, May Day or even a performer’s enlistment in the army, etc. Before the last war, chiming competitions were frequent; they have survived into our own days. Since 1982, Slovenian divinity students have formed a special Chiming Club, which organizes regional and national encounters of performing groups (the 1984 encounter was staged at Crngrob) and helps to keep the tradition alive.

So far there is little literature on Slovenian-style chiming. One of the first handbooks on the subject was Slovenski pritrkovavec, Navodila za pritrkavanje cerkvenih zvonov po številkah, by Ivan Mercina (Gorica, 1926), consisting of an introduction and 243 examples of chiming tunes, unfortunately recorded in a rather complicated and bewildering numerical notation. General discussions of the art can be found in Slovenska ljudska glasbila in godci (Maribor, 1972) and Ljudska glasbila in godci (Ljubljana, 1983) by Zmaga Kumer. There are also shorter articles and reports in various newspapers and magazines. The author of the present text has lectured or reported on this folk art various ethnographic conventions, both in Yugoslavia and abroad.

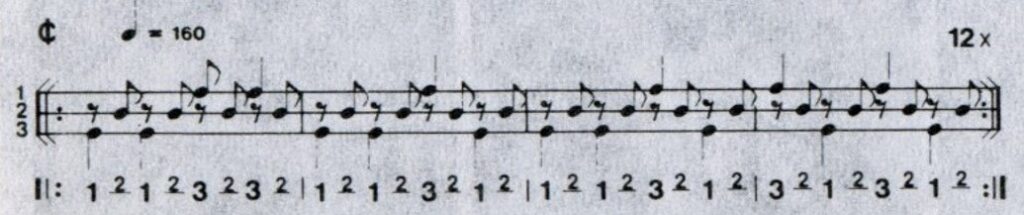

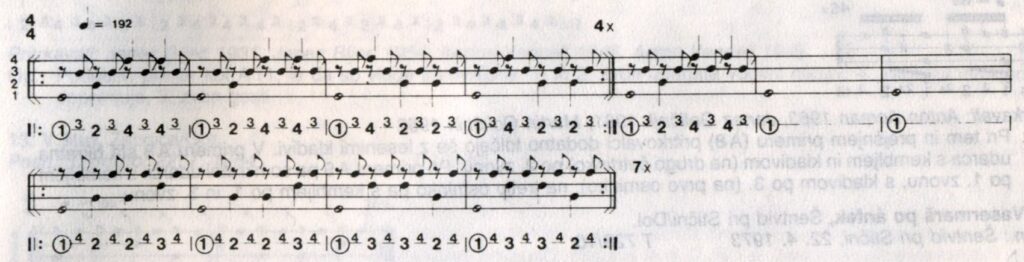

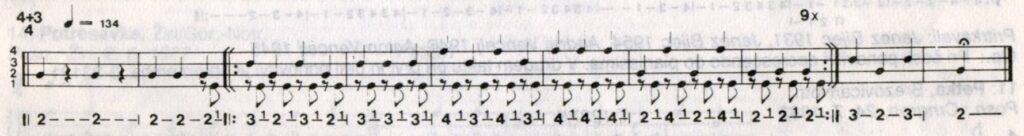

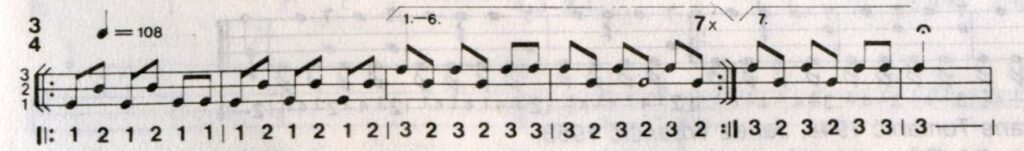

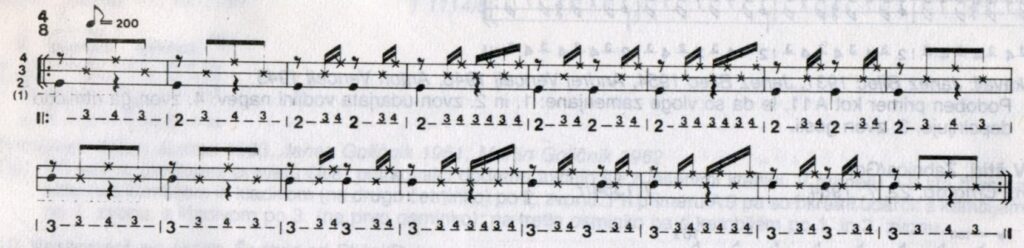

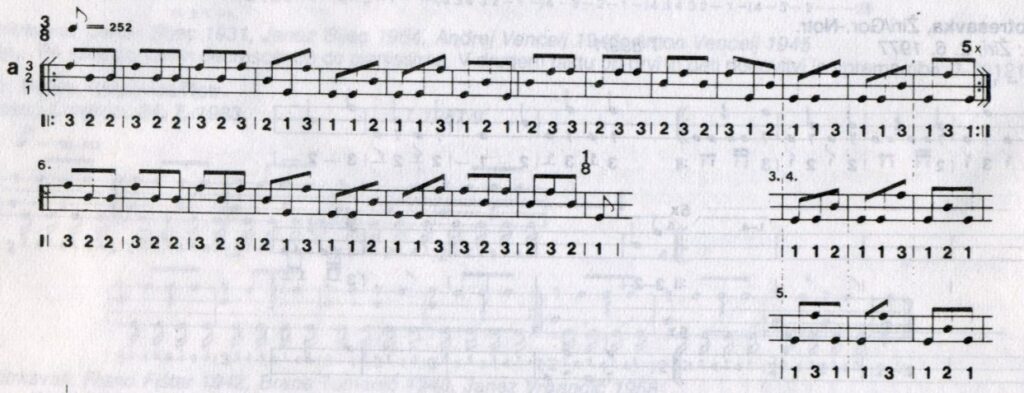

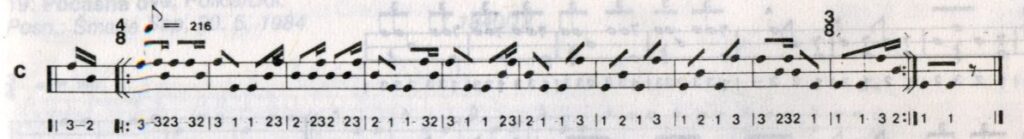

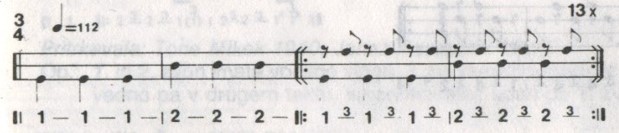

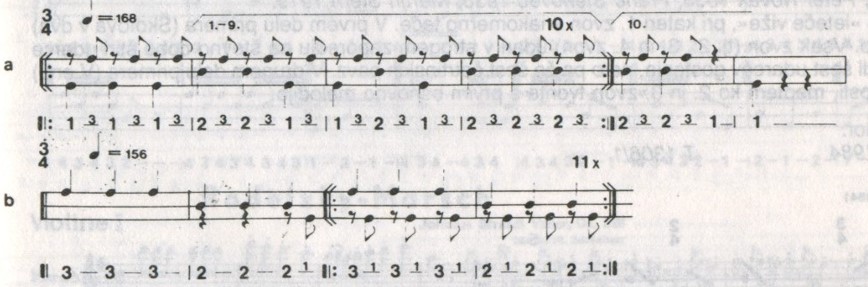

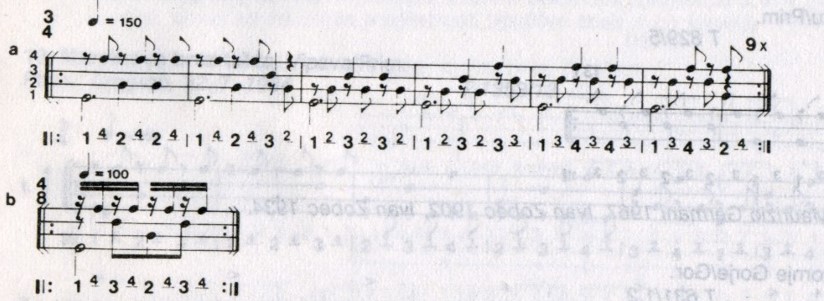

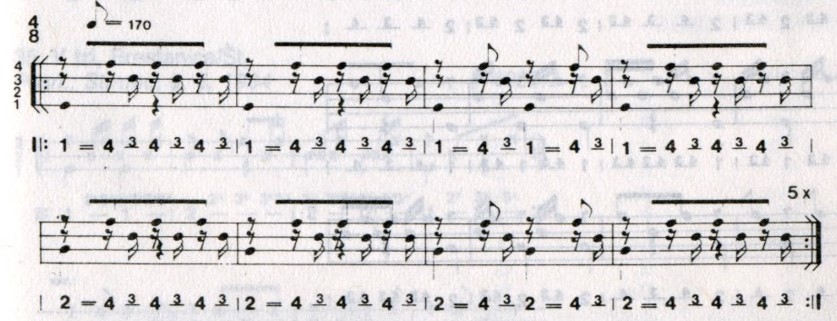

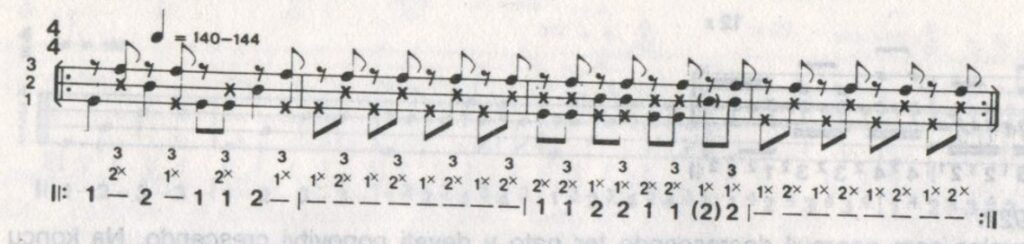

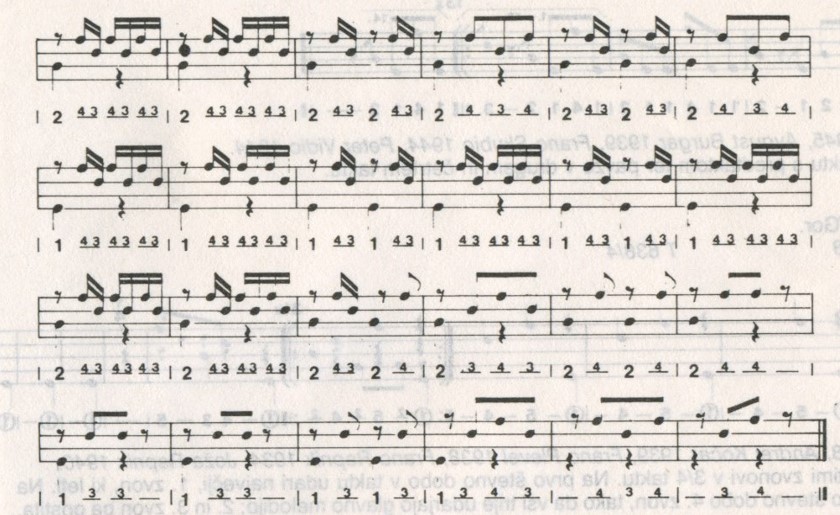

The tunes presented here are recorded conventional musical notation. The figures at the bottom of the lines mean: 1 = largest and lowest-pitched bell, 2 = medium-sized bell, 3 = smaller bell, 4 = even smaller bell, 5 = smallest and highest-pitched bell. A special list gives the precise values used in the various localities. A metronomic indication, such as quaver = 90-112, means accelerando. The basic tune is marked by crotchets, the “response” tune by quavers, the “embroidery” by quavers or semiquavers, * means a mallet stroke (e. g. 8, 9). A “flying” bell is marked by a semibreve or minim (5, 23, 37). In the case of melodic variations only major changes are indicated.

The figures added under the musical notation represent clapper strokes. In the case of tunes where all of the bells play an equal role, the figures are arranged in a single line (e.g. 7, 10, 16, 19, 24, 25, 36). A dash ( – ) represents a pause. A smaller figure over a dash means the bell playing the “embroidery” part. The exponent “x”, in combination with a figure means a mallet stroke. A circle around a figure stands for a “flying” bell. If two figures are written one atop of the other, two bells are sounded at the same time.

The heading of each transcription gives the name of the tune and the home village or town of the performing group, followed by the place and date of recording as well as the consecutive number of the tape in the files of our Institute (T 782/1,2). At the bottom of the transcription the names of the performers are listed in alphabetic sequence, followed by their respective year of birth. A broken line (—– ) indicates that the data are incomplete or irretrievable. In special cases explanations are added.

I wish to thank all who have in any way helped with the preparatory work or with the production of this record. In particular, I must thank the sound technician Matjaž Culiberg tor his expert conversion from tape to disc as well as his retouching of certain technically deficient field recordings. My most cordial thanks are, of course, addressed to all the performers, named or unnamed. At the same time I must present my excuses to all who could not be included in this selection, for the simple reason that the records in our files total more that 3000 minutes, of which only 42 minutes could be chosen for our record.

I sincerely hope this record will be an encoragement to all our folk musicians who strive to preserve this unique, typically Slovenian folk tradition.