May God Grant You a Good Year: Folksong Heritage from Adlešiči

GNI M 44.199

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Anka Adlešič, Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marija Peteh, Stanka Veselič, Marija Vranešič

The European custom of a bonfire on the night before Midsummer (24 June) was once known throughout Slovenia, but today this custom with all its expressiveness is preserved only in White Carniola. This is where the best-known Midsummer Eve songs also come from, sung by female Midsummer Eve singers in front of houses to wish good fortune those living there, as well as success with their crops and animals. The Midsummer Eve singers were also rewarded for their singing and well-wishes, most often with food, but sometimes with money. The Midsummer Eve singers always linked arms so that nobody could push their way between them because in folk belief this would have portended misfortune or even a death in the house. The singing was also connected with old pagan superstitions, which held that the singers could not make a mistake because this would also presage misfortune. The melody in this song is an older one, in which the singers “chase” each other, which means that one group of singers starts singing and, before the verse or musical phrase is finished, another group of singers begins a second verse. The singing thus continues uninterrupted until the end of the song. This type of singing in Adlešiči is somewhat reminiscent of antiphonal singing in church, but according to information from informants the reason for the uninterrupted singing is also connected with the belief that a wish or a song cannot be interrupted because this would bring misfortune.

GNI M 28.177

Recorded: Ljubljana, 1967

Narrated by: Marica Skube

St. George’s Day caroling as a folk festival welcoming the arrival of spring and its greenery was once popular across all of Europe, including Slovenia; it was preserved the longest in White Carniola, but even there it began dying out at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, the songs have been preserved. Today the custom of the St. George’s Day celebration is maintained by folkdance groups. In White Carniola, the young men would lead a boy clad in green from house to house, reciting or singing good wishes on the way. The White Carniolan St. George’s Day carols are unique because their content and style lean more upon the similar Kajkavian Croatian carols. They can be of various lengths, some of them preserve more pagan elements than others, and some spread good wishes; this recited version is heavily truncated and shortened, emphasizing only the desired essence.

GNI M 35.352

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marica Skube, Stanka Veselič, Marica Vranešič

Two metrically identical songs that differ greatly in content begin with this title verse. The first one is an old love song known throughout Slovenia about a cautious girl, and the second is a patriotic song, presented here. All indications are that the singers turned the well-known love song into a patriotic one at the beginning of the twentieth century. The White Carniolan singers also claimed that the well-known Slovenian poet Oton Župančič, a native of White Carniola, added new patriotic content to the old folk song’s metrical model.

GNI M 30.802

Recorded: Črnomelj, 1969

Sung and played by: members of the Adlešiči folkdance group

Beautiful Anka is definitely the best-known White-Carniolan dance, which many Slovenian folkdance groups included in their repertoire after the Second World War. The first audio recordings of this dance song were made in 1955 in Preloka and Adlešiči. We selected the recording from 1969, when the Adlešiči tambura players and singers participated in the St. George’s Day celebration in Črnomelj. The dance and the song were introduced to White Carniola from Croatia because versions of this song are known in the Drava and Sava valleys in Croatia and in nearby Severin (Ramovš, 1980). In White Carniola, the dance is primarily known in the areas formerly settled by the Uskoks (i.e., Preloka, Adlešiči, and Bojanci).

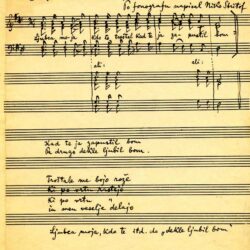

GNI wax cylinder no. 3

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1914

Sung by: Ferdo Požeg, Jurij Požeg, Mare Požeg, Miha Požeg, Kate Adlešič, Mare Adlešič, Miha Adlešič, Ane Rožman

The wax cylinder used on the phonograph had room for only one or two verses, and so this recording is truncated and the song is missing several verses. This dancing game in a sung form is known only in White Carniola, but it was a generally widespread children’s game with a recitation when the children held back the last one in line. The children’s version is evidently more recent and developed from an older adult game. In White Carniola the form of the adult bridge game varies by location because it was performed differently in Metlika, Črnomelj, and Predgrad. All three places had a castle, which explains the content and age of the dancing game and the accompanying song. The adults stood in two groups facing each other and sang questions and answers in call-and-response form. The lyrics were connected to manorial or feudal themes. Once a year, at least in their own minds, the serfs assumed authority from the lord of the manor and then they were able to reproach the lord (at least in song) for all of his mistakes, and the lords defended themselves (also in song) with accusations leveled at the serfs. Over time, the basic motif was preserved, but it was changed when the singers started introducing additional characters into the song. Some versions may therefore be longer, with a series of added criticisms at the expense of specific persons. The song and dance are preserved today only by folkdance groups.

GNI M 44.164

Recorded: Jankoviči pri Adlešičih, 1987

Sung by: Nežka Raztresen

This song about nostalgia for one’s single life was already transcribed in the nineteenth century; a number of versions of this song can be found across all of Slovenia. The White Carniolan version presented on this CD seems somewhat truncated because it omits all descriptions and focuses only on the conceptual core and the song’s lesson. The verse is dactylic pentameter with anacrusis, which is common in Slovenian alpine quatrains.

GNI M 44.206

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Anka Adlešič, Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marija Peteh, Stanka Veselič, Marija Vranešič

Back when the dead were laid out at home before burial, the family, neighbors, and friends would “guard” them, holding vigil by them, praying, and singing. This song is an example of such a wake song. The song was known throughout Slovenia at least since the nineteenth century and singers still sing it today, although in different surroundings or different singing opportunities. This wake song probably refers to the death of a young, still-unmarried girl.

GNI M 27.250

Recorded: Črnomelj, 1965

Played by: members of the Adlešiči folkdance group

In his Zbirka pokrajinskih pesmaric (Collection of Regional Songbooks), the composer Matija Tomc published a transcription and arrangement of the White Carniolan song Igraj v kolo jabolko (Play Apple in a Circle) in 1948, and then the Adlešiči folkdance group began dancing the Tribuče Kolo to this tune. This newly arranged dance takes the form of a “closed circle” (Ramovš, 1995) and came into being because White Carniolan folkdance groups needed new dances. The Tribuče Kolo spread to other White Carniolan folkdance groups and was also adopted by folkdance groups outside White Carniola.

GNI M 20.018

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1955

Sung by: a local woman

This song as it is known and sung today is fairly truncated because it ends with the girl releasing the fish she caught. Especially the older versions are longer and also include a love motif or story of a girl in love and the loss of her innocence. Because a song with this kind of content may have been seen as indecent, the singers began omitting the last part. Therefore some versions include a religious ending with human desires turned towards God. Unfortunately, the song was only first transcribed at the beginning of the twentieth century, so it is unknown whether the song is older and what it may have been like. It is tempting to think that the song may only be part of an older, forgotten fairytale ballad about the golden fish that promises to make any wish come true if it is released. This motif is known from the prose tradition. The song’s verse form (heptameter with anacrusis) and two-line stanza point to the song’s original ballad form.

GNI M 28.180

Recorded: Ljubljana, 1967

Sung by: Marica Skube, Marija Šuštar, Stanka Veselič

This version is a slightly truncated love ballad with the international motif of testing a young man’s love and fidelity. The song is said to have already been introduced to White Carniola by the Uskoks. It gradually lost its descriptive epic framework and lyricisim prevailed in it; in some versions one can feel a stronger shift toward making the lyrics more Slovenian. The Adlešiči version continues to preserve Croatian Ikavian elements, which suggests that the song was introduced from the northern Croatian Littoral. The Croatian versions transcribed in Baranja, in the Kolpa River area around Karlovac, and among the Burgenland Croats in Austria continue to preserve the strong narrative framework, so they are longer and include a wider variety of motifs (Terseglav, 1996).

GNI M 44.207

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Anka Adlešič, Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marija Peteh, Stanka Veselič, Marija Vranešič

According to the singers, this song was introduced to White Carniola by local young men in the 1920s. Among other things, the almost unchanged language with a firm Croatian basis also testifies to the fact that this song has not been present for a very long time in White Carniola yet. Even though this is a humorous love song, White Carniolans most often sang it while working in the vineyard.

GNI wax cylinder no. 20

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1914

Sung by: Ferdo Požeg, Jurij Požeg, Mare Požeg, Miha Požeg, Kate Adlešič, Mare Adlešič, Miha Adlešič, Ane Rožman

Because this wax cylinder recording is a hundred years old, the song is somewhat difficult to understand. Nonetheless this is the first recording of a love song that was already popular in the nineteenth century. The song uses a dialogue between a girl and her boyfriend to emphasize the girl’s sorrow at her boyfriend’s infidelity. Only the flowers, birds, fish, and nature in general can offer comfort to the girl, but her jealous boyfriend wants to destroy all of this, so that the girl has no comfort. The song is accompanied by an interesting comment from 1914, in which it is written that this was a “new song” (Kunej D., 2008).

GNI M 28.178

Recorded: Ljubljana, 1967

Narrated by: Marica Skube

On the liturgical calendar, 28 December commemorates the innocent children of Bethlehem, whom the Judean king Herod ordered killed. One memory of this is also ritual thrashing, which originated in pagan times, but the Church reconceptualized it. When children would go from house to house, they would symbolically thrash the people living there and wish them happiness in the New Year, for which they would receive a present.

GNI M 35.350

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marica Skube, Stanka Veselič, Marica Vranešič

This heroic ballad, which was introduced to Slovenia by the Uskoks, had an interesting fate. From the nineteenth century onwards, it has appeared in three language versions. The White Carniolan transcriptions and recordings have a fairly solid Croatian character, and the “Carniolan” version published in Slovenske pesmi krajnskiga naroda (Slovenian Songs of the Carniolan People) from 1838 is a mix of Slovenian and Croatian. Similar to the latter is also the nineteenth-century transcription by Josip Kocijančič from the Gorizia region. However, the Upper Carniolan version published in the first volume of Slovenske narodne pesmi (Slovenian Folk Songs) from the end of the nineteenth century, which were collected and edited by Karel Štrekelj, already has an almost completely Slovenian form. The transcription of the Uskok song in Upper Carniola is naturally extremely interesting. All of the transcribed versions prove that the White Carniolans borrowed the song from the Uskoks, and the Slovenians in the Gorizia region borrowed it from the Uskoks in the Littoral, and from the Gorizia region the song probably spread to Upper Carniola. Because the Slovenian musical tradition does not have an equivalent twelve-syllable melodic line, in which the song was originally created, the Slovenian singers adapted the verse to their metric and rhythmic principles and musical requirements, in which they divided the initial twelve-syllable line into two dactylic six-syllable lines (Terseglav, 1996).

GNI M 44.169

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Marija Cvitkovič

Up to the end of the nineteenth century all the versions of this song except for the one from Ihan, transcribed by Anton Breznik, were documented only in White Carniola, where the song is still part of living tradition today. It is a lamentation of love by a girl that no longer has anyone to pick flowers for because her beloved is far away serving as the castle scribe. Versions of this song were also known and transcribed in Croatia, so it is likely that it spread from there to White Carniola. This assumption is also supported by singers’ recollections that White Carniolan seasonal laborers heard the song in Croatia and brought it home with them.

RS N-2104

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1980

Sung by: a group of women

Among the church holidays a special place is held in folk devotions not only for Christmas and Easter, but also the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (15 August). In addition to the church holiday songs people also sang their own, which were never sung at church, but were part of folk devotions and part of the folksong repertoire. This song is one of these, in which, according to folk belief, on her holiday Mary takes various categories of people up into heaven: the unmarried, the married, widows, widowers, and so on.

GNI M 27.251

Recorded: Črnomelj, 1965

Played by: members of the Adlešiči folkdance group

This dance is known throughout Slovenia and came to White Carniola, where it is also sometimes called the šrotiš, from Lower Carniola. Today the dance is in the repertoire of practically all White Carniolan folkdance groups, usually accompanied by a tambura ensemble (Kunej R., 2008).

GNI M 20.060

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1955

Sung by: a group of women

This song is a toast that the wedding guests sang to honor the bride and groom. However, because any name other than that of the newly-wed couple could be inserted into the toast, the song was also sung on other occasions and among drinking buddies, in which the ending Živa žaba notri plava (A live frog is swimming in it) is almost an obligatory part of the toast. The ending is sung repeatedly until the one the toast is dedicated to drinks all the wine from the glass.

GNI M 44.196

Recorded: Dolenjci pri Adlešičih, 1987

Sung by: Anica Bahorič, Marica Bahorič, Katica Kapele

This song has many musical arrangements, probably due to its publication in various songbooks. Thus the text has been somewhat shortened because today it is only rarely heard in its entirety as a humorous family tree of wine, from the creation of the vine to the wine on the table. This recording features only the first verse of this song, which is known throughout Slovenia. The White Carniolan version has the refrain Oj, tam za goro (Oh, There behind the Mountain), which is also characteristic of some other Slovenian versions, or only uses a syllabic refrain (“trala- la,” etc.).

GNI M 35.354

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marica Skube, Stanka Veselič, Marica Vranešič

This lamentation of love, or a young man’s farewell from a girl that is marrying another, is a White Carniolan version of a folk song known throughout Slovenia. The song, which was first transcribed in White Carniola in the nineteenth century, has not changed much, but the nineteenth-century transcriptions show four-line stanzas, whereas in this recording the singers sing two lines that they repeat afterwards.

GNI M 35.358

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Stanka Veselič and Marica Vranešič

This song’s topic comes from the Kočevje-German and Slovenian ballad Smrt čevljarjeve ljubice (The Death of the Shoemaker’s Beloved), but it is so different in narrative, melody, and verse structure that it is entirely independent. The ballad underwent significant changes in other Slovenian regions as well, at least with regard to the earliest transcription of it from the nineteenth century, so that some versions are practically independent, short lyrical songs. Zmaga Kumer believed that the decay of this ballad came about due to its transfer into school choir lessons, where the ballad was first shortened and then further changed over time (Golež Kaučič et al., 1998). When the song came to White Carniola and in what form is unknown because the first versions were recorded there only in the second half of the twentieth century. It can be only assumed that the song began to spread from Adlešiči (where singers still consider the song “theirs” today) to other parts of White Carniola, where it is preserved by local folkdance groups.

GNI M 35.355

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marica Skube, Stanka Veselič, Marica Vranešič

This is a love ballad from Istria and the Kvarner Gulf that obtained a completely new subject and melodic form in White Carniola. Croatian versions of this ballad speak of two young lovers that spend the night in a green grove and in the morning they make up excuses to try to explain to their parents where they spent the whole night. The White Carniolan version takes only the first four verses from the Croatian one, and after that follows an independent Slovenian motif about lovers that die in a blizzard. This motif is not complete in the song, however; singers knew of it only from stories. The White Carniolan version is an independent lyrical song that shows how long it has been among the White Carniolans because it has been linguistically, stylistically, and melodically Slovenized (Terseglav, 1996).

GNI M 30.803

Recorded: Črnomelj, 1969

Sung and played by:members of the Adlešiči folkdance group

The song was introduced to White Carniola by the descendants of the Uskoks together with the dance. The song and dance spread primarily to areas along the Kolpa River (i.e., Adlešiči, Preloka, and Vinica). The song and the dance come from Serbia, only that there the dance is called zaplet or Opa, cupa, skoči (Ramovš, 1980). Like Beautiful Anka, the circle dance Pears, Apples, Plums has become a standard in the repertoire of folk dance-groups throughout Slovenia.

GNI M 20.058

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1955

Sung by: a group of women

This song about a drinker that wants to be buried in a vineyard when he dies was already transcribed at the end of the nineteenth century in Adlešiči by Ivan Šašelj (1906: 136). Other versions of the song can also be found in Styria and among the Kajkavian Croatians.

RS N-2102

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1980

Narrated by: a local woman

This song is one of many variations on White Carniolan Christmas carols that boys or children sang on Christmas Day in front of houses. Up to the first decades of the twentieth century most carolers were “Vlachs”, as the White Carniolans term the Orthodox population of Bojanci, or Greek Catholics from the nearby Croatian town of Žumberak. The singer in this carol alternates between singing and recitation, which is most apparent in the greeting at the opening of the carol. Most carols were sung.

GNI M 35.356

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1975

Sung by: Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marica Skube, Stanka Veselič, Marica Vranešič

This song about a girl that curses a boy after she finds him injured, nurses him back to health, and obtains his promise of marriage, which he then breaks, is known throughout the Balkans. There are many versions spread especially throughout Croatia, from where the song also came to White Carniola. In Balkan tradition, a girl’s curse carried the most weight and was even more damning than a parent cursing a child. Curses used to signify a real thing that everyone feared because people believed they had real consequences (illness or even death). Folk ethics held that not only unfaithfulness between married partners deserved to be condemned, but also that between young unmarried couples. White Carniolan versions and some Kajkavian Croatian versions are stylistically still more inclined to lyricism and leave out the epic elements so characteristic of ballads. The song originally had an eleven-syllable line, which the Slovenian singers subordinated to their melodic phrases, therefore singing the eleven Croatian syllables as a couplet containing a six-syllable line and a five-syllable one, a form known in the literature as the Nibelungen verse.

RS N-2102

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1980

Sung by: a group of women

This song of White Carniolan origin was transcribed as early as the nineteenth century and is known throughout Slovenia today because it was reprinted in various songbooks for primary schools and music schools. It is also performed by diverse musical groups in their own arrangements, but all of these are based on the arrangement by the composer and White Carniola native Matija Tomc, which is why most singers, especially in White Carniola, even consider the song his composition.

GNI M 44.203

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Anka Adlešič, Bernardka Adlešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič, Marija Peteh, Stanka Veselič, Marija Vranešič

This song is a version of a Midsummer Eve song (see no. 1) with a new, simpler, and no longer uninterrupted melody, which dominates in Adlešiči today. Despite their ritual character, ritual songs have also changed over time, in terms of both melody and lyrics. White Carniolan Midsummer Eve songs have several versions because the Midsummer Eve singers always adapted part of the words to the house they were singing in front of: specifically for young unmarried men and women and specifically for widows or singles. In some regions the Midsummer Eve singers were accompanied by a piper or bagpiper, who not only provided musical accompaniment but also acted as the singers’ protector so that troublemakers would not steal the singers’ gifts.

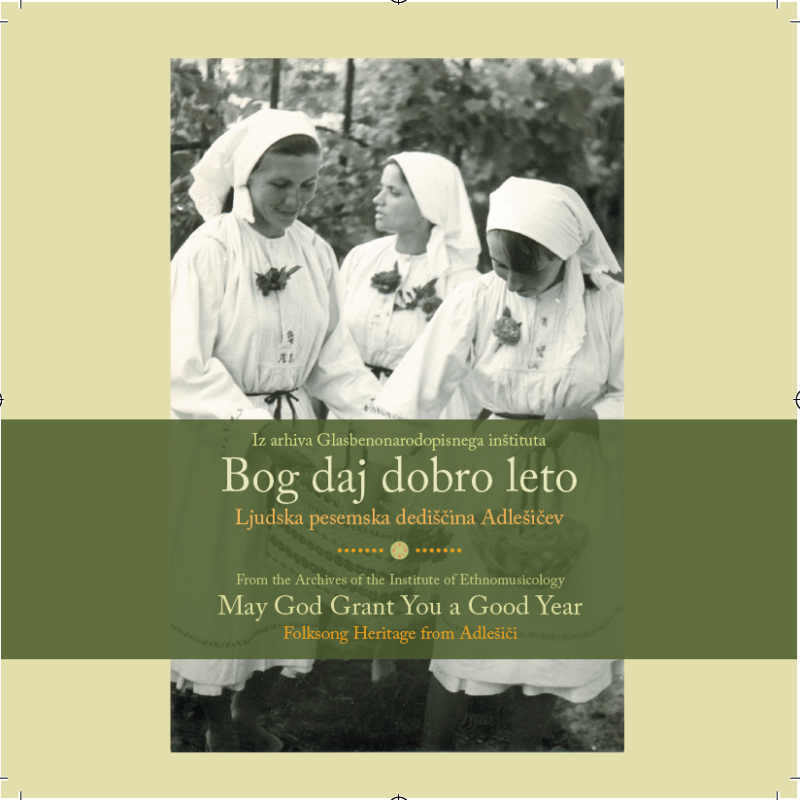

Marko Terseglav: Folksong Heritage from Adlešiči

Releases of audio recordings from the archives of the Institute of Ethnomusicology of the Scientific Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts generally present recordings from larger geographical or ethnic areas, or are thematic collections. This selection focuses on a single village, Adlešiči, which has long preserved its song tradition and is still cultivating it today. The credit for this audio publication goes to the singers of Adlešiči, who have always been aware of their cultural treasure and are also transmitting it to the younger generation.

In the 1870s Ivan Šašelj, the parish priest of Adlešiči, drew attention to the exceptional ethnographic richness of the village. He conscientiously wrote down the customs, sayings, and songs of Adlešiči and published them in the prominent Slovenian newspapers and journals of the time. In 1906 and 1909 he also presented this material in the independent booklets Bisernice iz belokranjskega narodnega zaklada (I in II) (Gems from the Folk Treasury of White Carniola, volumes I and II). In doing so he encouraged other enthusiasts and researchers.

The Russian musician and collector Eugenia Lineva made phonograph recordings of Slovenian folk songs in White Carniola as early as 1913. Although her recordings are still preserved and are kept in the audio archive in St. Petersburg, they have unfortunately remained inaccessible to us (Kunej D., 2008). Lineva’s recordings convinced the members of the Committee for the Collection of Slovenian Folk Songs to obtain its first wax-cylinder phonograph at the beginning of 1914. In June that same year the Ljubljana lawyer and White Carniola native Juro Adlešič used the phonograph to record thirty-eight songs in the villages of Preloka and Adlešiči (Kunej D., 2008). This was how the very first recordings of folk songs by a Slovenian researcher were created in Adlešiči. The performers were young singers between nineteen and twenty-five years old, except for one old-timer that was seventy-three years old. These recordings show that the song repertoire in Adlešiči at that time was similar to today’s, only that at that time part-singing and men’s singing was much more alive. Two songs (nos. 5 and 12) are included on the CD as an example of the first audio recordings.

The second important milestone in recording folk songs in White Carniola occurred in 1954. This is when the Institute of Ethnomusicology obtained its first studio tape recorder, and a few months later a portable one as well. This was donated to the institute by the amateur folklore specialist Josef Brožek, a psychology professor at the University of Minnesota. The first test of the new recording equipment was carried out in January 1955 in White Carniola, in the villages of Preloka and Adlešiči (Kunej, 1999). Examples of these recordings are represented by songs 9, 18, and 24 on the CD.

Researchers from the Institute of Ethnomusicolgy made recordings in White Carniola and in Adlešiči several times, in 1969, 1970, 1975, 1980 and 1987, and are continuing to record material today. A team from Radio Slovenia also made recordings in White Carniola for the broadcast Slovenska zemlja v pesmi in besedi (The Slovenian Land in Songs and Words), and so we have also included three of their recordings from 1980 on this CD (nos. 16, 25, and 27). We thank Radio Slovenia for giving us permission to use them.

Some recordings, especially those from 1914, as well as those from 1955, are technically deficient due to the poor-quality recording equipment of the time. This is especially true of the phonograph recordings, which are often unclear; nonetheless, they represent an important document because they are a priceless cultural and historical monument and memory. Thus, in arranging the audio recordings on the CD, we did not follow the chronology of the recordings to avoid possible monotony for listeners. For similar reasons we did not arrange the songs into thematic groups, but instead followed the principle of musical diversity, so that songs sung in unison alternate with part singing, recitative, and instrumental music. The song types represented on the CD are as follows: ballads (nos. 10, 14, 21, 22, and 26), ritual songs (nos. 1, 2, 13, 25, and 28), dance songs (nos. 4, 5, 8, 17, and 23), love songs (nos. 6, 9, 11, 12, 15, 20, and 27), a religious song (no. 16), a dirge (no. 7), drinking songs (nos. 18, 19, and 24), and a patriotic song (no. 3).

![Adlešiči folkdance group dancing to <em>My Beautiful, My Beautiful [Green Moutain]</em>, St. George’s Day, Črnomelj, 1972. (GNI photo library) Adlešiči folkdance group dancing to <em>My Beautiful, My Beautiful [Green Moutain]</em>, St. George’s Day, Črnomelj, 1972. (GNI photo library)](https://etnomuza.zrc-sazu.si/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Bog-daj-dobro-leto-4-250x250.jpg)