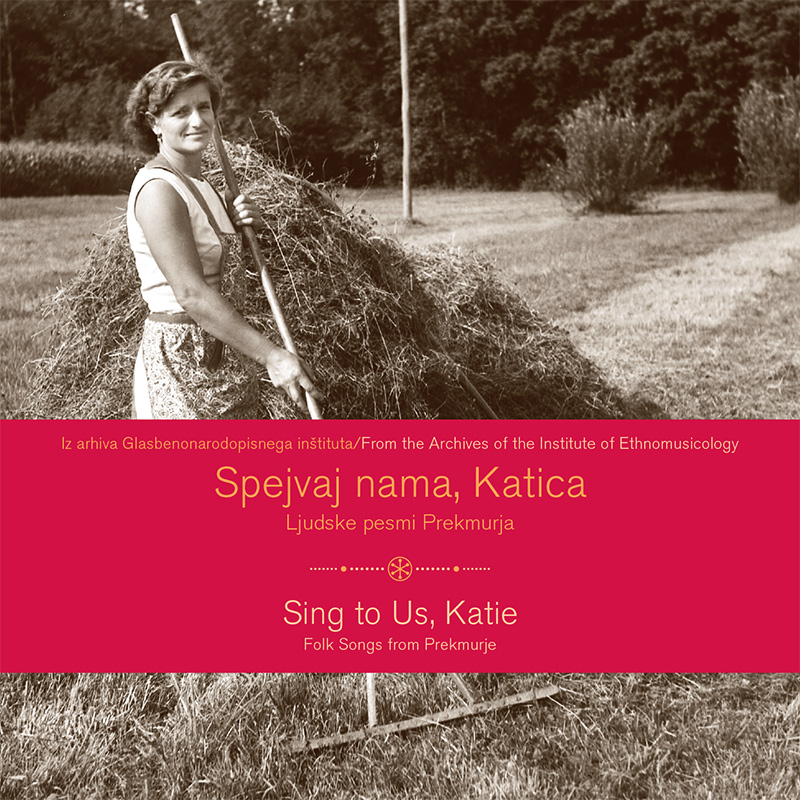

Sing to Us, Katie: Folk Songs from Prekmurje

GNI M 24.219; Love song

Recorded: Črenšovci, 1961.

Sung by: Matija Koštric (b. 1894).

The earnest love song “Spejvaj nama, Katica” (Sing to Us, Katie) is a heartbreaking depiction of a young woman’s helplessness within a patriarchal society, and at the same time a song about the pain of saying farewell to one’s beloved and the power of unselfish love. The song’s tragic nature has been mitigated through transmission: in an older version, the girl is an orphan (cf. Dravec, 1957: 250). The images of the sun, moon, and stars, which Katie wants to use to adorn her beloved’s blouse (róbača in the local dialect) give a symbolic meaning to the song.

GNI M 45.901; Love song

Recorded: Gomilica, 1990.

Sung by: Marija Cigan (b. 1919), Cecilija Horvat (b. 1934), Marija Raščan (b. 1949), Ana Hozjan (b. 1929), Kristina Lebar (b. 1936), Katarina Sobočan (b. 1932).

This song originated in central Slovenia, which is also indicated by the language used. The pain of discovering that a girl is marrying someone else is very common and helped these types of songs spread. This distress was often caused by the parents because they were the ones that selected their children’s spouses. The song seeks solace in nature: the birds are saying farewell to the bride on behalf of the young man.

GNI M 20.120; Ritual song, wedding song

Recorded: Beltinci, 1955.

Sung by: Ana Škafar (b. 1918), Franc Lebar (s. a.).

This is a wedding song in origin known in a wide area along the Slovenian-Croatian border. The memory of its original role has been preserved in a note by Števan Kühar: “A kind of very fast dance was once performed to this song” (Ramovš, 1996: 24). Prior to the Second World War, this role was overshadowed by a folklore-based dance game in which dancers chose their partners. This is one of the most popular Slovenian folksongs today, thanks in part to schools.

GNI M 45.925; Ritual song, wedding song

Recorded: Turnišče, 1990.

Sung and played by: Štefan Balažic (b. 1955).

This song was sung while transporting the bride’s dowry (Kda so pelali snehi omar). This usually took place one day before the wedding, on Saturday evening. The dowry included the most basic items that the bride (sneha) needed or had prepared for her new home. In places, saying goodbye in song has recently been replaced by an accordion player, but the transition from a sung to an instrumental song has retained characteristics of music to accompany movement. Together with the song, transporting the bride’s dowry symbolized the bride bidding farewell to her home, which is why this song could be sung along with the bride saying goodbye.

GNI M 27.819; Ritual song, wedding song

Recorded: Šalovci, 1958.

Sung by: Marija Janko (b. 1899).

The song “O zdaj, moja obseda” (Oh, Now, My Wedding Guests), published in 1807 in the book Starišinstvo i zvačinstvo (Traditional Wedding Organization; Kumer 2001: 126), was sung when the bride was being presented with gifts – that is, when her wreath was removed. This was also the symbol of the bride leaving the wedding table. The song displays features of early nineteenth-century folk culture: after the wedding, the girl’s hair ornament, a pearl ribbon (parta džundževna), was replaced by the head-covering worn by married women. The song is imbued with melancholy because to the bride the wedding meant leaving her home to live with strangers (tuhinci).

GNI T 254-B/15; Toast

Recorded: Pertoča, 1970.

Sung by: Irma Madjar (b. 1915), Marija Kozelj (b. 1909), Franc Partl (b. 1919).

The people of Prekmurje were known as hard workers. Although it is a winegrowing region, there were only few opportunities to spend free time at the table drinking. Therefore there were also few drinking songs or toasts. These were usually sung at weddings. This song was also borrowed from central Slovenia, which is why it has hardly any dialect features.

GNI M 22.176; Song about married life

Recorded: Čepinci, 1958.

Sung by: Lina Časar (b. 1886).

The seeming lightness in young woman’s song refers to the bygone time, or her maidenhood: in the sequence of songs on this CD, this song sounds like a bitter response to a forced marriage. The daughter openly reproaches her mother with having her married against her will: “What have you done by marrying me off?” Namely, in such cases marriage put an end to a carefree life, which could only be reclaimed after death.

GNI T 603/1; Ritual song, carol for a good harvest

Recorded: Ljubljana, Institute of Ethnomusicology, 1967.

Narrated by: Janez Žilavec (b. 1944), Ivan Pavšič (b. 1945), Jože Zver (b. 1943), Evgen Car (b. 1944), Janez Öri (b. 1946).

Early on St. Barbara’s Day, ritual participants (polažiči) made the rounds and would come into the house. Originally, these were young men and later on boys that wished everyone a good harvest and good luck to the livestock and people. They would usually find a log and kneel on it when invoking these wishes. People often prepared special cornmeal cakes for them. The customs connected with these processions were preserved longer in some places than others or they gradually shifted to around St. Stephen’s Day or New Year’s.

GNI Žižki, 24. 7. 2010/12; Ritual song, St. Lucy’s Day carol

Recorded: Žižki, 2010.

Performed by: Ivanka Žerdin (b. 1954).

On the eve of St. Lucy’s Day, figures masked in white called “Lucies” would go from house to house; they were the successors of the pre-Christian woman’s demon, the mid-winter witch (Kuret, 1970: 48). Their faces were also painted white, with long narrow teeth cut from turnips hanging out of their mouths. They carried pig’s eyes and forks on plates and by screaming and making noise they created the impression of being the dead come back to life. They threatened naughty children that they would gouge out their eyes. They also made noise on the roads using a special squealing voice, which served as an acoustic costume.

GNI T 254-B/1; Ritual song, good harvest carol

Recorded: Pertoča, 1970.

Narrated by: Vendel Ficko (b. 1897).

On the morning of St. Lucy’s Day, participants in processions made their rounds from house to house delivering good wishes in a special rhythmic manner by cackling. This represented caroling for the hens, to induce them to lay as many eggs as possible (Kuret, 1970: 50), which symbolized wealth. Especially in the twentieth century, this custom began to lose its ritual significance and was gradually transformed into a humorous message.

GNI M 22.108; Ritual song, New Year’s wish

Recorded: Markovci, 1958.

Narrated by: Mirko Kordič (b. 1943).

This ritual New Year’s wish consisted of rhythmic lyrics that young men used to wish good luck on New Year’s morning. In the GoriËko area, these visits were referred to as friškanje, named after the typical greeting they used. They performed this very early in the morning, at three o’clock. In most of Prekmurje, this custom has been gradually transformed: first, they would sing a carol in the vestibule (preklit) and then enter the living room (iža) to deliver their wishes. After the Second World War, this custom was assumed by elderly villagers in places.

GNI DAT 321/7; Ritual Christmas carol

Recorded: Gomilica, 2005.

Sung by: Olga Ropoša (b. 1936).

This Christmas and New Year’s carol begins with the greeting Falen bodi, Jezuš (Be praised, Jesus): it refers to “the New Year and Baby Jesus.” At the same time, the carol indicates a shift in traditional caroling: at Christmas, women gradually became involved in caroling as well. This provided a source of income to the poor in winter months; for these reasons, poor children (siromaška deca) also went caroling. Various cakes for the singers (pesmarske pogače) were prepared for the carolers; they were mostly made of cornmeal and in places were also called tepkance: small ones were made for children, and larger ones for grownups.

GNI M 24.270; Ballad

Recorded: Gornja Bistrica, 1961.

Sung by: Marija Šimen (b. 1912).

The more recently created ballad “Edna prevelka šuma je bla” (There was a Forest Too Vast) has a novel-like character: it spread as a narrative about an accident in the form of a song. These novel-like songs also had a didactic quality; this is why this song includes a moral, although it has no connection whatsoever with the unfortunate girl that died under a woodpile.

GNI DAT 322/2; Call

Recorded: Renkovci, 2005.

Sung by: Vincenc Pucko (b. 1925).

Traveling egg and poultry merchants announced their arrival in a village using special calls. Those that also traveled to Hungary had calls in Hungarian.

GNI M 24.241; Merchant’s song

Recorded: Črenšovci, 1961.

Sung by: Matija Koštric (b. 1894), Jože Cigan

(b. 1884).

This song is a rare preserved example of inviting people to buy things by singing: selling products at fairs or in villages demanded that the merchants draw people’s attention to them, and a good singer could achieve this through song; potters usually attracted buyers with calls similar to those used by egg and poultry merchants. This potter’s song also contains a comparison with the story of Adam and Eve.

GNI DAT 111/9; Military song

Recorded: Dobrovnik/Dobronak, 2000.

Sung by: Marija Varga (b. 1930).

The members of the Hungarian minority along the border have preserved various song genres. The outlaw and brigand Csali Pista falls into in the hands of armed gendarmes despite the warnings of the innkeeper’s daughter. When he sees he cannot escape, he sends his wife a message to care for their children and raise one of them as an outlaw.

GNI DAT 321/5; Ballad

Recorded: Gomilica, 2005.

Sung by: Olga Ropoša (b. 1936).

The song “Kata, Katalejna” (Katie, Katelyn) is one of the few ballads that refer directly to Prekmurje. It is about a brigand’s wife, whose husband kills her relatives. In this version, the wife, Katie, is in danger herself. Women usually sang these songs during collective chores such as making straw bags, spinning yarn, and weeding wheat, as well as hulling pumpkin seeds and husking corn, and in some places, also while stripping feathers.

GNI M 24.283; Ballad

Recorded: Gornja Bistrica, 1961.

Sung by: Ivan Kustec (b. 1880).

This song about saving dead relatives by playing the fiddle is considered an extension of the ancient legend of Orpheus and Eurydice (SLP I 1970: 282). In the song, St. Vitus assumes the role of the mythological musician, which gives the song a didactic and sermonizing character.

GNI M 24.229; Humorous song

Recorded: Črenšovci, 1961.

Sung by: Matija Koštric (b. 1894).

Despite the hard work, people also needed humorous songs in their everyday lives. This song does not originate in Prekmurje, which is also indicated by the Styrian expression for husking corn (kožuhanje). The colorful teasing comparison used in the song expresses general aesthetic norms: obesity was valued because it denoted prosperity.

GNI M 30.933; Military song

Recorded: Pertoča, 1970.

Sung by: Štefan Madjar (b. 1894).

The song provides a unique portrayal of military recruitment and thus offers an exceptional testimony to this event. The second stanza is about how young men experienced the committee’s evaluation: “We step into the room, / Twelve doctors sitting on chairs, / And I’m standing naked in front of them / Not even

knowing my name.”

GNI Žižki, 24. 7. 2010/8; Military song

Recorded: Žižki, 2010.

Sung by: Rebeka Bukovec (b. 1954), Marija Graj (b. 1955), Ivanka Žerdin (b. 1954), Anica Recek (b. 1951), Milica Žižek (b. 1951), Terezija Horvat (b. 1952), Marija Hodnik (b. 1954), Vida Prša (b. 1950), Terezija Gabor (b. 1946), Vera Horvat (b. 1951).

Boys and men brought various kinds of news from the army and sometimes songs were also used to deliver messages. Messages in the form of songs often contained traces of other languages and music environments such as the song “Banda svira” (The Band Plays). This song preserves the memory of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution because one of the versions mentions Ban Jelačić and Belgrade.

GNI M 24.202; Military song

Recorded: Črenšovci, 1961.

Sung by: Matija Koštric (b. 1880), Jože Cigan

(b. 1884).

The tragic experience of a military conflict is illustrated using simple folk metaphors: “The sun set behind the mountain, it is very sad.” The song expressed deep sadness and at the same time offered solace: during the First World War, the people of Prekmurje also sang military songs in the fire trenches.

GNI M 22.026; Love song

Recorded: Šalovci, 1958.

Sung by: Geza Prelec (s. a.).

This simple love song reveals the influence of Hungarian song tradition, which is emphasized by the exclamation šejhaj borrowed from Hungarian; this word is also known to other ethnic groups that used to live in the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary. The similarity is not coincidental: prior to the First World War, people from Prekmurje worked on Hungarian estates as seasonal laborers.

GNI DAT 322/1; Children’s song

Recorded: Renkovci, 2005.

Sung by: Vincenc Pucko (b. 1925).

The song expresses a well-known children’s warning, which played an even greater role in Prekmurje due to the presence of the Roma. The educational influence of school can also be perceived in the song.

GNI M 20.141; Children’s song

Recorded: Beltinci, 1955.

Sung by: Ana Smodiš (s. a.).

Children’s play was accompanied by songs, counting rhymes, and finger games. These rhythmic texts tended to accept new elements faster, while also preserving incomprehensible word combinations.

GNI M 20.142; Counting rhyme

Recorded: Beltinci, 1955.

Narrated by: Ana Smodiš (s. a.).

GNI M 30.894; Counting rhyme

Recorded: Lipa, 1970.

Narrated by: Darinka Horvat (b. 1959).

GNI M 30.895; Counting rhyme

Recorded: Lipa, 1970.

Narrated by: Darinka Horvat (b. 1959).

GNI DAT 112/53; Children’s song

Recorded: Dobrovnik/Dobronak, 2000.

Sung by: Marija Varga (b. 1930).

GNI M 45.843; Love song

Recorded: Turnišče, 1990.

Sung by: Neža Cipot (b. 1927).

Turning to saints for help was not common in the Prekmurje religious experience. The language used in this song also shows that the song was borrowed from central Slovenia.

GNI M 22.021; Love song

Recorded: Šalovci, 1958.

Sung by: Geza Prelec (s. a.).

This song is about the long years a girl served her lover, who promised her payment such as boots and a golden ring. The girl was left without her payment and also without her boyfriend, who left for the army.

GNI M 45.882; Moralistic song

Recorded: Turnišče, 1990.

Sung by: Ana Bojnec (b. 1915), Julijana Bojnec (b. 1919).

Due to the opportunity to evade the supervision of home, working abroad often raised moral doubts. This song expresses an open moral judgment against a girl that went off to Styria to work. The judgment was also aimed at the mother, who sent the girl away to work.

GNI M 22.096; Ritual song, dirge

Recorded: Šalovci, 1958.

Sung by: Marija Janko (b. 1899).

This song was sung when the deceased was being laid into the grave. It was published in the song book Katoliške mrtveče pesmi (Catholic Dirges). In each part of the ritual connected with death, a specific song was sung: before the deceased was laid in the coffin, while he was being laid in the coffin, when he was brought out into the courtyard, when he left home, on the way to the graveyard, when he was brought to the graveyard, and when he was laid in the grave. The most important testimony of this song heritage is the songs recorded in Šalovci in 1966 by the musician France Cigan; copies are preserved by the Institute of Ethnomusicology but they could not be included on this CD because of their technical shortcomings.

GNI M 26.114; Ballad

Recorded: Tropovci, 1963.

Sung by: Marija Rajbar (b. 1909), Pišta Novak (b.

1911).

The song about a widower at his wife’s grave is a type of ballad that was most popular in the twentieth century. Because of its moving content, which relied primarily on the helpless widower and his child, the song was easily spread and was thus also introduced to Prekmurje.

GNI M 27.811; Ritual song, dirge

Recorded: Šalovci, 1966.

Sung by: Marija Janko (b. 1898).

Over time, dirges completely replaced wailing for the dead in Prekmurje. This song expresses the calming hope and belief in happiness in the kingdom of heaven: “You’re going to the heavenly land!”

GNI M 30.892/1; Emigrant song

Recorded: Lipa, 1970.

Sung by: Jože Zadravec (b. 1922), Avgust Pal (b. 1932).

This heartbreaking song about emigrants with a realistic image of their arrival in the US reveals their deeply felt tragedy: the pain upon arriving in a foreign continent is expressed by the whistle of trains in New York that followed the arduous sixteen-day voyage across the sea. In 1910, 5,510 Slovenian-speaking inhabitants born in Hungary were registered in the US. The actual number of people that immigrated to the US from Prekmurje is probably 6,970; this number includes those that declared themselves “Wendish.” At the beginning of the twentieth century, the largest Prekmurje settlement developed in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania thanks to good train connections with New York (Kuzmič, 2001: 30–31).

GNI M 27.978; Religious song

Recorded: Toronto, 1959.

Sung by: Prekmurje emigrants.

The feeling of closeness expressed by the Christmas song “Zveličar prelübi” (Our Dear Savior) has multiple layers among Slovenian emigrants: it entails the connection that the song expresses with the words “Let peace make all the good people happy”; in addition, it reflects the closeness between the emigrants and their thoughts of their relatives in their homeland. The part-singing of church singers places this song within the context of a second homeland.

GNI M 24.209; Love song

Recorded: Črenšovci, 1961.

Sung by: Jože Cigan (b. 1884), Ana Hanc (b. 1897), Verona Cigan (b. 1894) and other singers.

Despite seasonal labor and emigration – or precisely because of them – love remained the central theme of Prekmurje folksongs. It overcomes boundaries and distances, which the song “Šetala se gori, doli” (She Strolled Up and Down), also known in regions bordering Prekmurje, expresses with even greater force. The song carries traces of separation and longing, which made it part of the Prekmurje identity. It introduces its symbolic message to the present time through images of increasingly distant reality: “He doesn’t till, he doesn’t plow, he only thinks about his beloved.”

Marija Klobčar: Stories in Songs from Prekmurje, or What Katie Sang About

The lyrical song Spejvaj nama, Katica (Sing to Us, Katie), which begins and also lends its name to this collection of songs from Prekmurje, gives a special meaning to this audio publication. It is not merely a heartfelt love song, which sketches the sun, moon, and stars on the horizon of its longing: it is a song that uses its simple expressiveness to talk about the people that have created, preserved, or changed the song heritage of Prekmurje. It is sung by the elderly Matija Koštric. His singing makes the song sound like the memory of an experience from a distant youth, and calling up this memory reveals traces of the song’s richness. By placing this song at the beginning of the audio publication, Spejvaj nama, Katica represents an invitation to a melodic story about everything that was worth remembering: it heralds the sung messages compiled in this song collection.

The audio publication Spejvaj nama, Katica provides insight into the problems and joys of simple everyday life in Prekmurje, which for centuries has been defined by a marginalized lifestyle primarily focused on farming. The Mura River separated Prekmurje from other Slovenian regions and, until after the First World War, this separation was further exacerbated by the fact that the area fell politically and administratively under the Hungarian Crown. Such marginalization is also tangible in the region’s significantly poorer level of development, which also influenced its folk culture. The region’s cultural image was influenced by Protestantism, fostered by subordination to Hungarian feudal lords. The subsequent formation of a specific literature in the Prekmurje dialect is also reflected in song heritage.

Efforts to strengthen religious convictions, accompanied by efforts to increase people’s knowledge in general, relied on literary texts written in dialect that increasingly approached a Prekmurje regional supradialectal form starting in the eighteenth century (Novak, 1976). All of this indirectly influenced the character of folk culture, including songs. A number of hymnals were created by both the Lutheran and Catholic communities. While taking a closer look at the Goričko area, the Prekmurje priest Jožef Košič critically commented on this situation in 1824, stating that “all that the Slovenians in the hills care about is how to read a little and write with great difficulty, which they only practice by copying lyrics” (Košič, 1992: 37).

Reproduction of songs is not highlighted here by coincidence: audio recordings made in Prekmurje in the second half of the twentieth century showed the great influence of locally printed hymnals. This was especially pronounced in dirges and wedding songs: the song “O zdaj, moja obseda” (Oh, Now, My Wedding Guests) on this audio publication directly continues the tradition of the book Starišinstvo i zvačinstvo (Traditional Wedding Organization), published in 1807 in Sopron (cf. Kumer 2001: 126). Customs and songs thus changed under the influence of the Reformation or Catholic efforts. Changed ritualism also resulted in a changed character of songs associated with the seasons and work. Only in this light is it possible to understand Košič’s assessment of Slovenian singing in the area between the Mura and Rába rivers: “They only sing church songs because there are no secular ones” (Košič, 1992: 47).

The strong influence of Protestantism, which was strengthened by Enlightenment goals in the eighteenth century, thus caused a more rapid replacement of rituals that preserved pre-Christian elements. The Catholics also strove to replace these with new religiously appropriate songs. Thus in Prekmurje – in contrast to socially comparable White Carniola – one seeks songs about spring rituals in vain, even though individual elements prove the hidden preservation of Midsummer’s Night customs even at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Košič, 1992: 47).

Nonetheless, Prekmurje has preserved certain special features in its winter customs: the fear of perishing along with the rest of the natural world was most pronounced at this time and outweighed the religiously-oriented prohibitions. Therefore, special forms of partially Christianized pre-Christian rituals were preserved in this area: they began on 4 December (St. Barbara’s Day), and then continued on St. Lucy’s Day (13 December), which in some places was moved to St. Stephen’s Day. The carolers (known as polažiči) were initially grown men, but later on the custom passed on to boys. Alongside these rituals, completely Christianized customs were increasingly used connected with carol singing around Christmas, the New Year, and Epiphany, ending with Candlemas. Gradually, women also became involved in caroling, although this process was not uniform; in some areas, there were even differences between individual villages.

The special feature of Prekmurje connected with the presence of Protestantism can also be perceived in the extremely poor representation of legendary songs and songs about the Virgin Mary. An overview of ballads recorded in Prekmurje also proves that these were few in number; the majority of these are not of local origin (Kumer, 1967: 151). The reasons for the relatively small number of ballads are not ideological: ballads were common predominantly in more developed areas, which Prekmurje certainly was not. At the same time, ballads represented news, but the relatively isolated and poor Prekmurje region did not attract the bearers of such tidings.

The people of Prekmurje had only limited contact with the inhabitants of neighboring regions, restricted mostly to fairs and pilgrimages: “Like the Slavs in general, the people of Prekmurje like to sing songs. It is nice to hear their melancholy voices when they come to us, to Sveta Trojica v Slovenskih Goricah on a pilgrimage or to Sladka Gora near Šmarje, but they also sing merry and humorous songs” (Meško, 1882: 522). This image began to change in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the people of Prekmurje began working as seasonal laborers in fields far from home.

Material deprivation forced the people of Prekmurje to engage in seasonal labor. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the population of Prekmurje nearly doubled (Fujs, 1995: 280), and so at the end of the nineteenth century emigration emerged as another social pattern alongside seasonal labor (cf. Kuzmič, 2001). The great fragmentation of farms, which was the result of Hungarian inheritance laws, only further aggravated this material deprivation. Thus, for nearly a century, seasonal labor was one of the most characteristic features of Prekmurje. For example, 9,108 people from Prekmurje traveled abroad for seasonal labor in 1939 (Šarf, 1985: 40). This work also provided an opportunity to come in contact with a different world, either on Hungarian estates, where they worked primarily before the First World War, or on the fields of Slavonia, Vojvodina, Germany, and France. As field-workers, they labored in groups of up to 150 or 200 people, which provided an excellent opportunity to exchange songs. Seasonal labor thus changed the traditional song heritage of Prekmurje: “We could hardly wait for them to come back from their seasonal work, so we could hear the new songs they had learned” (Dravec, 1957: xvi). Working on the other side of the Mura River (i.e., in neighboring Styria) also had an exotic appeal for borrowing songs.

Working abroad rapidly changed the traditional culture of Prekmurje, and these changes became part of the new Prekmurje identity. This was most evident in architecture; the changes in customs and traditions, as well as songs, were less evident from the outside. After the Second World War, Josip Dravec, who transcribed songs in postwar Prekmurje, called attention to the traces of these changes: “Today we can find manuscript songbooks in Prekmurje from the interwar period that contain almost no old Slovenian folksongs” (Dravec, 1957: xvii). Some folksongs from Prekmurje were nonetheless recorded even before 1919, when Prekmurje joined the other Slovenian regions as part of the new Yugoslav state. These include not merely the rare transcriptions known to central Slovenia, such as individual publications by Stanko Vraz (1839) or Števan Kühar’s transcriptions from before the First World War, but also the most valuable testimonies, which long remained unknown. In addition to Košič’s transcriptions (Novak, 1976), these also included the wax cylinder recordings that the Hungarian researcher Béla Vikár made in Tišina in 1898. Slovenians only learned about these nearly a century after they were made; they are the oldest audio recordings of Slovenian folksongs (Odmev prvih zapisov, 2004).

The recording team of the Institute of Ethnomusicology first came to Prekmurje in 1955 and then continued to return, especially during the 1960s. That was a time of great cultural differences and distances between disappearing traditional culture and new elements introduced by economic development. In the mid-1960s, when radios were first bought in the countryside, there were still some people that went to church barefoot in bad weather and only put their shoes on before entering the building. In villages, potters were selling their products laden on carts, and at the same time ice-cream vendors were selling ice cream on gravel roads and – like the egg and poultry dealers a decade before – inviting people by yelling out “Ice cream, ice cream for one egg! Come and bring your eggs!” This audio publication thus reveals the diversity of song messages and the character of changing life. In terms of content, it combines three levels. First, it is a narration of the lives of individuals, which is why it touches on their most important milestones between birth and death. Among these, customs related to weddings and death appear the most important in terms of songs, accompanied by a few rhythmic children’s lyrics. Personal narration begins and concludes with love songs, which occasionally also appear in a series of other songs. The frequency of love songs draws attention to the fact that they were the most common in Prekmurje (Dravec, 1957: xlviii), while at the same time illustrating the continuously emerging new life. Songs connected with caroling customs are also interwoven into this story: they are meant to ensure that the fields are fertile and that livestock and people prosper. These songs accompany messages that express a wide variety of perspectives on society itself, such as ballads, and humorous, military, and moralistic songs. The toasts also contain expressions of social ties. A special message is conveyed by songs directly expressing separation from home: these are songs connected with emigration and emigrants. The audio publication also includes two songs by the region’s Hungarian minority.

The diversity of Prekmurje’s song heritage is also reflected in the linguistic level of the songs included on this audio publication: some songs are sung in dialect, others have a supradialectal character, individual songs reflect linguistic features of neighboring regions, and others are close to standard Slovenian. In some songs, these levels change; sometimes differences can even be seen between individual words. The songs also differ in their technical quality because the recordings were made at different times. Due to their technical shortcomings, some valuable recordings could not be included on this audio publication.

The content of the songs on this audio publication is purposely interwoven; interspersing ritual songs among songs expressing the distress of life diminishes the frequently overly-idealized image of the folk characteristics in them. This audio publication highlights the beauty of song heritage without idealizing life: it therefore places songs connected with weddings between two bitter responses to a wedding. Until the Second World War, the outwardly picturesque and traditionally-oriented weddings often lacked an understanding of the newlyweds’ personal feelings. At the same time, the audio publication leaves room for personal expression and longing, which in Prekmurje were also strengthened by seasonal work and emigration.

The soundscape reflected by this audio publication was, therefore, not only constructed by the Prekmurje of the past; it was also created by the ties with places and people that the people of Prekmurje encountered on their paths to earn a living. In the last thirty years, these traces have been joined by reflections of today’s understanding of Prekmurje song heritage: thanks to performances by Vlado Kreslin and the ensemble Beltinška Banda, Prekmurje’s musical heritage has marked and enriched the variegated sound of Slovenian song heritage. Prekmurje, which until the First World War was practically unknown to central Slovenia, thus attracted the attention of musical performers in central Slovenia. In recent years, this song heritage has also been consciously continued by folksong groups. With the views this audio publication offers of the unfamiliar otherness beyond the Mura River, Spejvaj nama, Katica joins the echoes and messages of this soundscape.

Urša Šivic: Musical Features of Folk Songs and Singing from Prekmurje

The selection on the audio publication Spejvaj nama, Katica (Sing to Us, Katie) emphasizes the lyrics of the songs; however, this selection is also melodically rich. It demonstrates contacts between songs and singing from Prekmurje and from Central Slovenia, and it also highlights the special features of Prekmurje’s song and singing heritage that distinguish it from “Alpine” heritage, revealing its distinct character and connection with neighboring Hungary.

The special features of Prekmurje songs are refl ected in both the rhythmic and tonal systems, which draw attention to archaic layers that predated major and minor keys (cf. Dravec, 1957: xxix–xxxiii, Vodušek, 1990: 90–93). Major-key tunes predominate in the material presented; however, the relatively frequent presence of minor-key tunes, either in a “modern” minor or its modal predecessors (songs nos. 18, 35), draws attention to how the music of Prekmurje is related to that of Hungary (Vodušek, 2003: 89–91; song no. 16). Some songs have three- to six-tone modal sequences (songs nos. 1, 3, 36, 37); moreover, some songs (nos. 36, 37) have not taken on a major tonality but have preserved the threetone system (nearly consistently) even in the lower part (cf. Vodušek 1990: 93–94).

According to Josip Dravec, “the characteristic rhythm of Slovak and Hungarian folksongs appears nowhere” in Prekmurje and he also claimed that syncope was not common in Prekmurje folksong (1957: xxxviii). The majority of songs recorded in Prekmurje and released on this audio publication display the rhythm typical of central Slovenia, although examples can be found in which syncopated rhythm occurs as a fragment or a constituent part of the rhythmic pattern (songs nos. 1, 36, 38). In contrast, the rhythmic and melodic structure of the song “Rozmarinska vejka” (Sprig of Rosemary) clearly shows that this is a dance song transferred from Hungarian tradition.

Like in central Slovenia, in Prekmurje as well the most common form of two-part singing consists of an upper part known as na mladòu (literally, the “young voice”) and a lower part, or na staròu (literally, the “old voice”) in parallel thirds or sixths (Dravec, 1957: xliv; Kumer, 1975: 102, 103). In selected places, the lower part moves more freely, which creates intervals of fourths and fifths (songs nos. 22, 32, 38). In this, “clearly expressed harmonic functions of individual scalar steps occur” (Dravec, 1957: xliv) because individual tones in the lower part take on the role of the bass, which is presumably a remnant of a singing style based on the tradition of singing the lower melody in a tetra- and pentatonic system (songs nos. 36, 37). The example of “Zveličar prelübi” (Our Dear Savior) is very interesting; at least in fragments of this song, melodic steps typical of a tetratonic system can be heard in the upper part (Vodušek, 1990: 91–92).

Because the people of Prekmurje began replacing “their old local songs with songs from other lands, especially from other Slovenian regions” after the First World War (Dravec, 1957: xvi), one would expect that the Prekmurje singing style would have also begun changing or that the central Slovenian method would have been increasingly used; however, little evidence of this can be found in the material recorded by the Institute of Ethnomusicology. Accordingly, two-part singing remains a typical feature of Prekmurje singing today – in contrast to central Slovenian part-singing, which includes the bass – even in cases when a group is singing and one of the upper melodies is duplicated in the third, lowest part (songs nos. 2, 21, 38). In the lower vocal register, this part substitutes for the bass; the predominance of this group singing method shows that two-part singing is a constituent part of Prekmurje “multi-part” harmony and that bass-singing in the sense of harmonizing with and accompanying the upper two parts does not have the acoustic or aesthetic role that it largely does in other parts of Slovenia (cf. Dravec, 1957: xlv, Šivic, 2010: 8–10).

In terms of art music, Prekmurje song heritage, with its special dialect, melodic, and rhythmic features and characteristic tonal systems, is a constant in the oeuvres of Slovenian composers. In addition, it has also secured a place in pop music (e.g., Vlado Kreslin and Katalena). Their adaptations reach a wider audience and have thus made many Prekmurje folksongs popular. In this way, a number of Prekmurje songs have become generally known through various music channels; for example, “Sam se šetao gori, doli” (I Strolled Up and Down), “Vsi so venci vejli” (All the Wreathes have Withered), “Zrejlo je žito” (The Grain is Ripe), “Kata, Katalena” (Katie, Katelyn), “Vöra bije” (The Clock is Striking), and “Ne orji, ne sejaj” (Do Not Till, Do Not Sow). Some of these have been included on the audio publication Spejvaj nama, Katica; hearing them sung in a folk manner thereby complements their adapted versions and broadens our knowledge of the music of Prekmurje.