Slovenian Folk Songs I: Historical, Heroic, Legendary, and Fairytale Narrative Songs

SLP I, 5/8, C, pp. 46–49; GNI M 25.448

Sung by: M. Micelli (1895); Recorded: 1962; San Giorgio, Resia, Italy

This song is classified as historical because the chief figure here is King Matthias, yet some Slovenian folk songs simply borrowed his name, probably to replace some other hero in the original song. The story about the rescue of King Matthias is known also to other peoples, mostly Slavic. The song would probably have been forgotten by now if it had not been preserved by singers in Resia, who still sing it today; there are only two known transcriptions dating from the nineteenth century. The melody of the song has a rising and falling pattern, it has a comparatively broad range, and it indicates an underlying tetratonic basis.

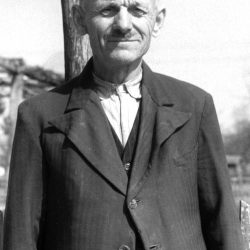

SLP I, 14/26, pp. 91–92; GNI M 27.731

Sung by: M. Tekavec (1896); Recorded: 1966; Dane, Lower Carniola

In 1789, Austrian troops led by Ernst Gideon von Laudon defeated the Turks at Belgrade. The victory resounded throughout Europe and the field marshal’s name started to appear in songs that were eventually reprinted in school textbooks, thereby becoming part of oral tradition as well. This was also the case in Slovenia, where the song has been preserved to this day. In connection with this Austrian victory, however, we should point out a fact that is often overlooked. Namely, the principal victor at Belgrade was in fact the prominent Slovenian mathematician Jurij Vega, who had stolen in very close to the walls and precisely calculated the ballistic curves for the Austrian artillery that subsequently destroyed Belgrade. Because official reports and these songs only praised Laudon, his figure passed into Slovenian folksong, echoing the euphoric spirits of the time in Austria. This song has a simple two-part tune essentially using four different notes. The duple meter interpolated between sections in triple time is characteristic of Slovenian song tradition.

SLP I, 19/33, pp. 114; GNI M 24.413

Sung by: A group of women at the Spruk home Recorded: 1961; Hrib near Kamnik, Upper Carniola

The song came originally from the Kajkavian dialect region of Croatia and passed into the Slovenian regions of Prekmurje and White Carniola, where it is now most widespread. It probably originated among the Uskoks (Serbian refugees that fled the Turks). Its text and pleasant melody helped it spread throughout Slovenia, where it gained topical interest primarily during World War I. Variants continued to spring up during World War II. This melody is sung everywhere with only slight alternations, so it has probably spread only recently. This recording represents a simple type of three-part singing, in which the upper parts are sung in parallel thirds and the lower part sings bass.

SLP I, 23/12, pp. 139; GNI M 24.438

Sung by: M. Štaudohar (1914), A. Jordan (1889) and K. Štrk (1888);

Recorded: 1961; Predgrad, White Carniola

This theme of three women (fairies or witches) is of South Slavic origin and was brought to White Carniola by the Uskoks. This represents a genuine ballad: a song sung to accompany the kolo (circle) dance as it was performed until very recently by White Carniola residents at the winter bonfire for St. John the Evangelist’s Day, 27 December. Today the song and the dance related to it are preserved and cultivated by folklore groups. The song gives the impression that it contains a love motif, one that metaphorically expresses which of the three women (the mother, sister, or sweetheart) is his true love. Other South Slavic variants, however, demonstrate that originally this was actually a legendary song in which mythological creatures (e.g., fairies and witches) obtain power over the young man by tearing out his heart. The Kočevje Germans borrowed the song from the White Carniolans. This single-verse song has a three-part melody; here, the upper two parts sing in parallel thirds and the lower one is a kind of drone dwelling mostly on the tonic.

SLP I, 23; GNI M 31.124

Sung by: M. Kolar (1927); Recorded: 1970; Podlehnik, Styria

The variants found predominantly in northeastern Slovenia, in Haloze, are stylistically, melodically, and functionally somewhat different from others. This song type probably came from the Kajkavian dialect region of Croatia, but this song has been in Slovenia so long that it has been completely nativized, adapted to Slovenian musical and stylistic tastes and norms. Thus it represents a specifically Slovenian version of this South Slavic theme.

SLP I, 24/3, str. 144; GNI M 20.713

Sung by: M. Jankovič (1878); Recorded: 1956; Loka near Mengeš, Upper Carniola

This ballad about the river man is of Slavic origin, although it is also known among the Germans east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, territory that was once inhabited by Slavs. Among Slovenians the story has been known at least from the sixteenth century onwards, and in the seventeenth century it was published by Valvasor. The story is more commonly found in the popular narrative tradition, but the song can also be traced from the eighteenth century onwards. This version is interesting because the singer originally “censored” it, leaving out the cruel ending about the river man’s revenge on the children. This censorship had a practical basis because she sang the song as a lullaby for her grandson. The Slavic origin of the song is also demonstrated by its text, which consists of two verses in strict heptameter. The melody has two parts, with a large range and wide intervallic leaps.

SLP I, 27/5, pp. 152–153; GNI M 24.160

Sung by: A. Hanc (1897); Recorded: 1961; Trnje, Prekmurje

This fairytale text about a cursed prince is mostly found in folk narrative, but it also exists as a song with this motif mostly in Prekmurje, where Stanko Vraz transcribed it. It is still occasionally sung there today, and it is also sung by Slovenian emigrants in the United States. The song is both rhythmically and melodically interesting. The purely pentatonic tune, which is also used in other Prekmurje songs, has a rhythmic framework in which sections of duple, quintuplet, and sextuplet rhythms alternate.

SLP I, 32/6, pp. 163; GNI M 21.573

Sung by: F. Jemec (1898); Recorded: Žeje near Moravče, Upper Carniola

The region extending from Domžale to Mengeš and Kamnik is known for its living and rich ballad tradition. The largest number of old ballads were discovered here, including this one, which tells of a disobedient daughter that is cursed and transformed into a fish, but is later saved by her brother. In the song this brother is most often a saint (St. Anthony or St. Lawrence). The White Carniola variants are somewhat different stylistically and melodically, primarily resulting from the influence of the Croatian Kajkavian dialect tradition. This song type has not been found in other Slovenian regions. The song text comprises two-line stanzas, sung here to one short, simple melodic phrase, constructed from four notes.

SLP I, 33/25, pp. 178–180; GNI M 27.863

Sung by: J. Melchior (1888); Recorded: 1966; Feistritz an der Gail, Carinthia, Austria

European and Slovenian fantastic ballads and the fairytale tradition both contain the theme of punishment for a disobedient child, who is turned into a fish or bird or is carried off by the Devil because he has been (im)prudently cursed by his parents. This is shown in some song types in SLP I. This song also has a similar motif, but the reason for the parental wrath is somewhat surprising: a daughter refuses marriage, usually because she is too selective, until finally the Devil himself, disguised as a suitor, comes to get her. Most versions have happy endings because the girl appeals to the Virgin Mary or Christ to rescue her from the Devil. In the nineteenth century this song was most often transcribed in Styria and Prekmurje, but some variants were also transcribed in central Slovenia. This recording is from the Gail Valley in Carinthia, and it differs from other versions, especially those from Styria and Prekmurje, in some of its motif elements. The tune has a recitative rubato form.

SLP I, 33; GNI M 30.049

Sung by: G. Kozel (1896), A. Vidovič (1947), M. Kranjc (1948), M. Kranjc (1911), M. Emeršič (1932), V. Ivančič (1945) and J. Turk (1950); Recorded: 1969; Velika Varnica, Styria

In the twentieth century this song was most often transcribed in Upper Carniola, whereas today it is most widely known in Prekmurje, the Rába Valley, and Styria. The differences between these versions are not only chronological but also reveal somewhat different poetic renderings of the same motif. The story itself is most likely medieval and is also known among other European peoples, but predominately in narrative versions. Although several variants of the song were published in SLP I, we decided to use a more recent, technically better recording that has not yet been released. Recordings of this group in Velika Varnica in Styria were a genuine surprise when they were made; up to that time, ethnomusicologists had believed that three-part and four-part singing were known only in Carinthia, but these recordings overturned that belief. The song is interesting not only for the voice-leading but also for its vocal technique, which is reminiscent of that in Resia. This technique has also recently been found to be spread throughout Slovenia, although not in such a pronounced form.

SLP I, 39/22, str. 207; GNI M 25.100

Sung by: A mixed group of singers; Recorded: 1962; Gozd near Kamnik, Upper Carniola

This theme, which is known all over Europe, is mostly found in narrative form. It is likely that the story passed into folk tradition either from sermons or from examples cited in sermons, and the priests probably borrowed it from literature. Song versions of the story are found not only in Slovenia, but also in France, Spain, and Flanders. The motif was also used in classical music in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni. In contrast to other European versions, the Slovenian version tells only of a wanton man that is punished with death because of his disrespectful attitude toward a dead man’s bone. The older, primary motif of the dead man as a wedding guest is attested in Slovenia only in variants from White Carniola. The song is a typical example of the three-part singing style most widespread in Slovenia today. The upper two parts carry the melody in parallel thirds while the lower part sings bass. The rhythm is also interesting: there is alternation of triple and quintuple rhythms throughout.

SLP I, 43/31, pp. 235; GNI M 24.190

Sung by: M. Koštric (1897); Recorded: Žižki, Prekmurje

According to popular belief, students of divinity (secondary school graduates) knew how to produce hail and practice sorcery. Above all, their theological knowledge allowed them to forecast sinners’ destinies and “determine” their punishment, as portrayed in this song. All of the Slovenian variants, from Upper Carniola to Prekmurje, indicate specific popular legal and ethical norms, according to which the greatest sin was fraud, or dilution of wine with water. Allowing for regional differences, there are also other unpardonable sins, such as infanticide, carousing, disrespecting one’s parents, and so on. The three-part octameter verse structure can still be felt in the song, which is almost purely pentatonic, with two-line stanzas and mostly quintuple rhythm. These elements indicate the ancient origins of this song.

SLP I, 46/18, pp. 251; GNI M 23.411

Sung by: J. Kastelic (1940) and F. Kastelic (1937); Recorded: Zagorica (Dobrepolje), Lower Carniola

This theme, once again a rather frequent one in the narrative tradition, occurs in songs predominantly in central Slovenia (Ljubljana, Kamnik, and Škofja Loka and their surroundings, and Lower Carniola). The familiar theme of death and attempts to escape it also acquires a social note: it is mainly the rich (in this case the miller) that want to escape it because their hearts are too enamored of material goods. Folk songs, however, express the generally known truth that nobody escapes death. The song is classified as a fairytale song because death is personified in fairytale fashion and not simply as a general notion or an event. The motif also occurs in other European traditions and in various genres.

SLP I, 48/23, pp. 277–278; GNI M 25.530

Recorded by: M. Clemente (1899); Recorded: 1962; Uccea, Resia, Italy

See commentary for no. 15.

SLP I, 48; GNI M 32.513

Sung by: F. Labric (1914); Recorded: 1970; Felsőszölnök, Rába Valley, Hungary

The Christian tradition predominates in all Slovenian variants of this song; the theme itself, however, goes back to Antiquity with the motif of Orpheus saving Eurydice from the underworld. This motif is familiar in all European cultures and also most Asian ones. Currently it is thought that the Greek motifs reached Slovenians by two routes: either through European literature or folk tradition, or by indirect routes from Asia, via the Balkan Vlachs, who passed them on to the South Slavs and then to the Slovenians. On this CD the motif is presented in songs from two extreme points in Slovenian ethnic territory: Resia and the Rába Valley. The Resian example is a more recitative narrative style, with a tetratonic melodic basis but no unifying metric pattern, whereas the example from the Rába Valley is a two-line song in heptameter with a refrain.

SLP I, 51; GNI M 28.213b

Sung by: I. Jemec (1904) and F. Peterka (1896); Recorded: 1967; Kokošnje, Upper Carniola

The memory of the pagan custom in which the gods were to be offered a tithe (one-tenth of the harvest and livestock, or the sacrifice of the tenth child) is preserved to today through this song. Christianity preserved only the offering of the harvest tithe but abolished the child sacrifices, except at the symbolic level. Folk tradition viewed the tenth child as supernatural and something that could harm the family, in particular when it was a daughter. A tenth son was believed to be endowed with supernatural gifts. Thus in Christian environments the tenth daughter was often banished. The motif is familiar throughout Europe, but only in narrative; Slovenians have preserved it in song form. The song about the tenth daughter is known also among the Kočevje Germans, who borrowed it from their Slovenian neighbors. The beginning of another song that functions as a lament when someone dies has been appended to this one because it shares the same meter and rhythm, but it has nothing in common with the tenthdaughter theme. The fairytale setting is also lost and replaced with a legendary one.

SLP I, 59/8, str. 323–324; GNI M 28.351

Sung by: C. Močnik (1915) and J. Močnik (1918); Recorded: 1967; Poreber, Upper Carniola

It was only through Bürger’s Lenora (familiar to Slovenians in Prešeren’s translation) that the motif of the dead bridegroom established itself in the intellectual consciousness of Europe, even though it was also known in the pre-Bürger tradition. The Slovenian folk tradition once again received this motif from the Greeks, obviously through the mediation of the South Slavs, who had borrowed it from the Vlachs, a Romance-speaking people. In Slovenia the Lenora of Prešeren’s translation has become part of the popular song tradition, a transformation that came about naturally because the story, meter, and rhythm are the same as ones already present in folksong. Thus Prešeren’s translation was easily paired with the melody of an existing folk song about a dead bridegroom. These melodies are what allow folk songs to live and spread. Today the best-known variants of this folk song come from Lower Carniola (Zagorica), but because the CD already features one song from this area we have chosen a variant from the Tuhinj Valley in Upper Carniola.

SLP I, 61/8, pp. 332–333; GNI M 23.968

Sung by: A. Lisac (1911) and M. Južnič (1912); Recorded: Slavski Laz, White Carniola

This song or motif is known not only to the Slovenians but also to the Croats and Bulgarians, which indicates that it represents an older Slavic tradition. This song type, A, differs from types B and C, which are of more recent origin and no longer contain a fairytale motif, whereas the motif of the curse is still present in type A. The song probably originated somewhere in Upper Carniola and in the course of time spread throughout Slovenia, including to Kostel on the Kolpa River, where this recording was made. The song is a simple single-verse tune with a two-part melody. The two singers commented that “this isn’t a pop song, it’s just some kind of drivel, it’s not even a tune or anything.” Similar opinions of short, ancient tunes are common, especially among younger singers.

SLP I, 62/7, pp. 340; GNI M 27.109

Sung by: A. Košmrl (1909) and M. Košmrl (1947); Recorded: 1965; Gorenji Lazi, Lower Carniola

This is a motif similar to that of the preceding song, except that here the girl casts a spell on her unfaithful suitor to punish him with illness for marrying a richer girl. The song thereby suggests the social motive for his unfaithfulness. This type of song is of more recent origin, probably the eighteenth century. The song has two-line stanzas and a three-part melody (ABCB), so every stanza is repeated twice, except the last one, which already has four lines. The singers sing in parallel sixths, with the upper part taking the lead.

SLP I, 63; GNI M 24.646

Sung by: F. Premrl (1886); Recorded: 1961; Škoflje, Littoral

In this most recent song type, the fairytale motif of a curse has been completely lost. Only the two previous variants suggest that this song also deals with a similar kind punishment, even if in this case the girl punishes the lad that marries a foreigner (a Tyrolean girl). The song is currently known throughout Slovenia, but since the fairytale motif has been lost it is now known simply as a love song. We decided to include here an unpublished variant from the Littoral in order to represent that region on this recording. An interesting feature of this song is the alternation of triple and duple rhythm. The text is divided into two-line stanzas and the melody has three parts (ABAC), and thus in each stanza the first line is repeated three times.

SLP I, 65; GNI M 34.740

Sung by: T. Bezovšek (1915); Recorded: 1974; Vrhpolje by Kamnik, Upper Carniola

Slovenia’s older folk songs indicate that once upon a time the abductor of girls was a fairytale-demonic being, half animal and half devil, called Ulinger or Lajnar. That is why this song is classified as a fairytale song, even though the demonic being has already been replaced by a gypsy. In contrast to Ulinger, the gypsy entices the girl with drinking songs and no longer merely through music. The more recent variants featuring the gypsy as the seducer no longer have a tragic end, whereas Ulinger cruelly destroyed the girls. A more recent variant from Upper Carniola that has not yet been published in SLP has been selected for this CD. The three-part melody (ABC) with alternation of duple and triple rhythm requires that the second line of each stanza be repeated in the two-verse text.

SLP I, 66/5, pp. 371; GNI M 22.802

Sung by: M. Pesjak (1904) and F. Pesjak (1935); Recorded: 1959; Koritno, Upper Carniola

In a sense, this song is a continuation of the previous song’s motif, but now it has been considerably modernized. The motif of enticing the girl is now intermingled with another one: the gypsy playing cards to win the girl.

Marko Terseglav: Historical, Heroic, Legendary, and Fairytale Narrative Songs

The idea of accompanying the printed volumes of Slovenske ljudske pesmi (Slovenian Folk Songs) with a CD of sample recordings first arose in the course of preparing the fourth volume. However, because the sixth volume of Slovenian Folk Songs concludes the cycle of ballads (or narrative songs), we initially decided to wait for the publication of that volume and only then to bring out the recordings. However, great popular interest in folk songs persuaded us not to postpone releasing the recordings. We noted that people who already own the printed collection published by the Slovenian Society, as well as everyone that loves folk music would listen to the recordings. Because our work has received both moral and material support from the Scientific Research Center of the Slovenian Academy of Science and Arts and from Slovenian Radio-Television, our project has finally come to fruition, and so we now present the first compact disc in the Slovenian folk music CD series.

The recordings on this audio publication are presented as arranged in volume one of Slovenian Folk Songs (SLP I). The volume was published in 1970. It presents 67 types of historical, heroic, legendary, and fairytale songs. This classification is also used on the audio publication, but only twenty-two sound recordings are presented. Some of the songs published in the book were transcribed as early as the nineteenth century and some at the beginning of the twentieth century. As such recordings of all the types of songs are unfortunately not available. Recordings exist, however, of the songs that people still sing today. Occasionally, it also happened that a sound recording of a particular category of song was found but was technically too poor to be included on the audio publication. It must be taken into account that most of the recordings were made by members of the Institute of Ethnomusicology, not always with the best equipment and also not in the studio, but in the field, among the people in their houses where singing would be interrupted by other voices, pauses, talking, and so on. The recordings selected are therefore not all of the highest quality. In some of them, individual words or the first stanza may be missing. Our purpose was not to offer technically perfect recordings by professional singers, but rather to present documentary recordings of Slovenian folk singers. In some instances we debated whether or not to include a particular recording because of its poor sound quality: if it was included, this was because it is interesting because of the melody or text – or the song in question represented the only recording of that specific type and therefore has high cultural and historical value in itself. This means that all of the recordings provide a highly valuable illustration of Slovenian song heritage. We are confident that our listeners, aware of the documentary and illustrative value of this material, will welcome and treasure this recording.

We realize that not every CD owner has a physical copy of SLP I, in which these songs are presented with detailed commentary and the appropriate scholarly notes. Each recording is accompanied here by a short commentary for clarification, as well as an indication of where the particular song is found in the SLP I collection. Six of the recordings have no such indication, which denotes that these recordings were made available to us only after the publication of SLP I and that we therefore had to use more recent sound recordings. In addition to being a sound supplement to the book SLP I, this audio publication is valuable and sufficiently illustrative for any listener.

Slovenian folk singing is characterized by multipart singing, and accordingly we wanted the audio publication to offer as many renderings of songs sung in multiple parts as possible. The difficulty here arises from the fact that ballads in particular have become rather rare today and can still be sung only by a few individuals. Our archives, therefore, mostly contain recordings of only a single voice. We have also avoided using multipart singing recordings that have already appeared on other records or cassettes. As much as possible, our selection also takes into regional representation into consideration, but a particular place or region may nonetheless be missing, whereas others may be represented twice. In some regions, song material was more abundant, whereas in others certain types of motifs are no longer known. In order to avoid relying too heavily on recordings from the same region, we occasionally opted to use a technically lower-quality recording from another part of Slovenia with the goal of representing the regional variations in Slovenia as comprehensively as possible.

Our series of audio publications opens with ballads, or narrative folk songs. These are songs that have one single dramatically emphasized event. The term “narrative song” was used even in the nineteenth century by the great Slovenian collector Karel Štrekelj. In folklore studies, literary concepts like the ballad, the romance, and the bylina (Russian epic song) and others are used interchangeably.