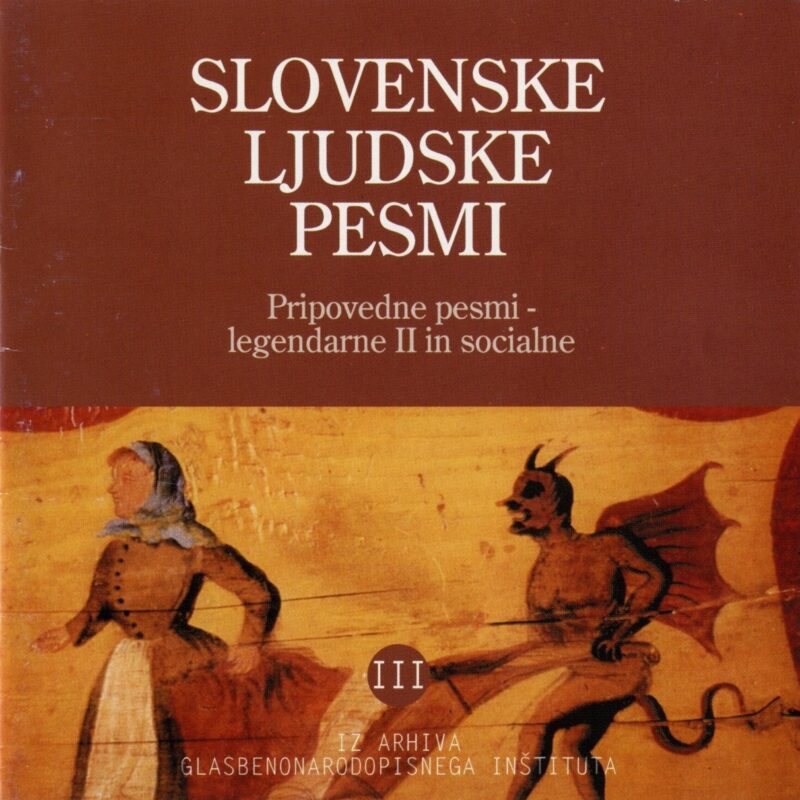

Slovenian Folk Songs III: Narrative Songs - Legendary II and Social Songs

GNI M 21.380

SLP III, p. 10, p. No. 142/13

Sung by: Frančiška Jemec (1898 – 1967) Recorded: 1957

Most variants of this song come from the Kamnik and Moravče area, and so we probably have a locally limited tradition determined by the circumstance that a road passed through here along which goods were transported from Styria to Ljubljana and further on to Trieste. Additionally, there is an altar dedicated to St. Peregrin in the church at Brdo near Lukovica. But in the biography of this saint (d. in 1330) there is nothing to serve as basis for the content of the song.

The verse pattern of this song is the trochaic heptasyllable with anacrusis, and the stanza is twolined, with refrain. The melody is in six-eight time. The beginning of the sound recording is in view of a technical fault introduced gradually.

GNI M 23.559

SLP III, p. 45, p. No. 151/32

Sung by: Marija Jeras (1908) in Ivana Dacar (1920); Recorded: 1960

Judging by the metric pattern of the text, characteristic of a dancing song, the song could not have originated before the 18th century, probably after the example of morally instructive stories. The melody is in 3/8 time in two lines, although as regards the stanza one might expect it in four lines.

GNI M 24.094

LP III, p. 80, p. No. 153/39

Sung by: group of singers; Recorded: 1961

Longer than elsewhere on the territory of the Aquileian patriarchate a belief in the forgiving of the worst sins (e. g. of murdering one’s parents) after life-long penitence was preserved. Since the missionaries from Aquileia were also teaching among Slovenes, it is believed that in the 8th or in the 9th century they passed on this example from the sermon, which provided the event for the song about a repentant sinner to whom after his life-long penitence Jesus granted redemption. In the course of time in the song, Jesus has been replaced by Mary, who as an omnipotent intercessor either herself forgives the repentant or lets him know that he is forgiven.

The verse pattern of the two-line stanza (with repetition of the first line) is the trochean distich in the octosyllable and heptasyllable, yet the pause after the fourth syllable indicates that the original pattern of the stanza was made only of a sequence of octosyllables. It is also a characteristic of this example that the leading singer sings himself every first verse of the stanza; others repeat It and add the second verse.

GNI M 32.610/1

SLP III, p. 84, p. No. 153/46

Sung by: Jožef Šraj (1902); Recorded: 1970

For the contents of this widely spread and still currently performed song cf. the preceding number. The verse pattern is also identical: the four-line stanza is made through the repetition of the dIstIch, which corresponds to the four-line melody in three-four time.

GNI M 23.972

SLP III, p. 117, p. No. 158/41

Sung by: Alojzija Lisac (1911) in Marija Južnič; Recorded: 1960

The song is based on a moralistic example as is evident from the first written record from the end of the 18th century. The originally very long text, has in the course of time, been shortened so much that only the core of the story still remained. Since also in stylistic and formal respects it had come closer to our song tradition, this song could become known all over Slovenia and remain preserved to these days.

The four-line melody of this example constructed in six-eight time requires a repetition of the two-line stanza made up of the trochaic heptasyllable and hexasyllable with anacrusis.

GNI M 21.303

SLP III, p. 143, p. No. 160/22

Sung by: Andrej Kranjc (1867); Recorded: 1957

The content of this song is an instructive story about a landlady, who out of greed refused hospitality in her tavern to a traveller. She haughtily rejects the good luck offered by God and in turn – as punishment – loses all her property within a night. The song was originally not bound to the mountain Limbarska gora and to the saints – “bothers” Valentine and Peregrin. St. Valentine’s church on Limbarska gora is from the 17th century, and the altar of St. Peregrin in the church on Brdo near Lukov1ca from the 18th century. Both saints appear in connection with Limbarska gora in the song only in the middle of the 19th century. In a record written down by M. Valjavec. In this form the song has come down to these days through school textbooks and song-books. The selected example in the trochaic heptasyllable with anacrusis is interesting for its alternating 3/4 and 2/4 times and the three-line melody for two-line stanza with the reiteration of the second verse, which increases the duration of the already long text so much that it could be as a whole reproduced on the audio publication.

GNI M 24.277

SLP III, p. 182, p. No. 162/40

Sung by: Marija Simen (1912) and Rutina Kustec (1923); Recorded: 1961

The song belong into the group of those legendary-instructive songs which deal with “contrapasso”, in other words, which tell the listeners that in the other world one is punished for what he has committed in this world. The description of infernal torments relates the Slovene tradition to the Central European one, although the Slovene cases in their present form, with many native features, come from the 18th century.

This text again is shaped in the 18th century trochean heptasyllable, the characteristic verse pattern of our narrative songs. In the example here selected from Prekmurje the song Is made up of four-line stanzas, while the melody shows the influence of the neighbounng Hungarian tradItIon.

GNI M 28.991

SLP III, p.187, p. No. 162/47

Sung by: Nežka, Rezka and Lenčka Zore, Angelca and Mica and Milica Virjent; Recorded: 1968

The variant of this song, stemming from Gorenjska, appears to be a more recent one, the verse pattern being the trochaic distich of the octosyllable and heptasyllable. The singers named above were adapting the text to the four-line melody in 2/4 time by reiterating all the two-line stanzas in full. That the song became much longer in this way was no obstacle, as it was sung when keeping vigil over a deceased person.

GNI M 24.278

SLP III, p. 192, p. No. 163/6

Sung by: Marija Simen (1912) and Rutina Kustec (1923); Recorded: 1961

In its content, the song is related to the idea that the human soul appears in the form of a bird. It expresses trust into Mary as mediatrice for sinners (birds sing to Her), and ends with the warning that the biggest, almost unforgivable, sin is despair over God. Whereas the verse pattern – the trochaic hexasyllable – relates the variant from Prekmurje to an older tradition from the Pannonian areas, the four-line melody shows the influence of the neighbourhood of Hungarian songs.

GNI M 26.132

SLP III, p. 195, p. No. 164/3

Sung by: Terezija Petek (1910); Recorded: 1963

According to its content, the song belongs among legendary-instructive ones, with a tinge of social protest: the hardheartedness shown in the denial of hospitality and almsgiving is the fault of the landlady, and the punishment for its awaits her in the next world.

The variant chosen shows an antique outward form as to the three-line melody in two-four time; the next is suited with four-line stanza or with a two-verse one through the repetition of the second verse.

GNI M 25.173

SLP III, p. 215, p. No. 168/8a

Sung by: Franc Kenda (1898); Recorded: 1962

The idea of weighing in the other world as the divine judgement is not originally Christian, as it can be traced into the ancient times, straight into ancient Egypt. Christianity took over this idea, but the weighing of souls was at first not a task imposed on St. Michael. He was held to be the protector of graveyards, accompanying the souls to the other world. But at the beginning of the 12th century, he starts to appear in some manuscripts with scales in his hands and on the frescoes of mediaeval churches, including Slovene ones, where we see him weighing souls. These songs are mediaeval in origin. In the Baroque period, new admixtures came up, e. g. Mary’s intercession at the moment when everything appears to be lost forever.

A special feature of the example chosen is the recitative manner of singing, which represents in our tradition an exception and has so far been found only in the vicinity of Kobarid. Our singer who at a particular point passed from the recitative into a dramatic declamation claimed to have heard as a child the song sung by somebody from the same village and was carefully drawing on his way of presenting the song. It is significant that he was singing with equal attention to detail both when the song was being written down and, after a lapse of 10 years, when recorded.

GNI M 28.598

cf. SLP III, No. 179

Sung by: Antonija plesec (1928), Elizabeta Sušnik (1896), Trezika Vodušek (1920), Zefa Podkrižnik (1896); Recorded: 1967

Because of its initial stanzas the song about Mary and the wounded soldier could be regarded as a soldier’s song, but towards the end it so clearly becomes a pious one that at least with some certainty it can be ranked among legendary songs. In individual variants there is at times more stressed the beginning, at other times the ending. The dactylic rhythm of the verses classifies this song among the more recent ones, and the mention of “Francozovsko” (France), where the boys are going, suggests that the song originated at the time of the French wars. The earliest written record is from the thirties of the previous century.

GNI M 26.868

SLP III, p. 292, p. No. 179/74

Sung by: locals led by inž. M. Šipka; Recorded 1964

The polyphony sung by women from the Savnija valley is contrasted here with the typical polyphony of men from Carinthia. The leading inner part begins with the half of the first verse of each stanza, and then all the singers join in. In the four-verse melody the first line is always repeated, which makes it possible that through reiteration two-to-four verse stanzas of the text are adapted to it.

GNI M 30.587

SLP III, p. 301, p. No. 180/14

Sung by: Ivka Cerar (1909), Janči Šraj (1898), Terezija Šraj (1907), Pepca Mikel (1903), Angela Perne (1917), Kati Škerjanec (1903), Terezija Jerek (1902); Recorded: 1968

St. Lucia, a native of Sicily, suffered martyrdom at the time of Emperor Diocletian. According to legend she put out her eyes to avoid a bothersome suitor. Therefore, she was portrayed with a pair of eyes on a tray in Slovenia at least from the 16th century onwards. Among the churches dedicated to her in Slovenia, the most well-known is the one at Skaručna, built in the 17th century, and it is dedicated in gratitude for miraculous recoveries. One of such churches offered the basis for a song which otherwise speaks of the martyrdom of St. Lucia but not in accordance with the legend; its main story is about the recovery of a farmhand from Moravče. Therefore is seems probable that the song, known otherwise also in the broader surroundings of Moravče, came up in the 18th century, when the present church at Skaručna represented a well-known pilgrimage site. The formal construction of the text and the melodies of the preserved example likewise classify the song with recent lore.

GNI M 24.625

cf. SLP 111, p. No. 186

Sung by: Francelj Foški (1879); Recorded: 1961

The content of this song comes from a more recent version of the German ballad “Ritter und Magd”, spread widely on leaflets in the 18th century. The narrative song, about a nobleman who seduces a simple girl and then for a substantial sum of money leaves her over to a farmhand, is independently known also among other European nations. But the similarities between our variants and the German ones are so big that their relationship is clear. Because our variants have been documented only in the broader Trieste area (as well as one example in Bovec), it may be assumed that one or two leaflets accidentally came into Austrian Trieste and thus through Slovene translations reached Slovenes.

GNI M 31.732

SLP III, p. 329, p. No. 187/12

Sung by: Treza Kühar (1924) and Ana Cuk (1919); Recorded: 1970

The song, which has so far been written down only in Stryia and in Prekmurje, including Porabje, narrates the same story as the previous song, but transferred into domestic, rural environment. The verses of the text, in old Slavic tripartite heptasyllable, are linked into two-line stanzas, or in conformity with the corresponding three-line melody in three-eight time; each verse is repeated three times, as in the example chosen from Porabje. In view of the fact that the earliest written record comes only from the beginning of the 20th century, it may be assumed that the song originated a little earlier, but the verse pattern and the style of the text permit also a greater age, and clearly and independent treatment.

GNI M 28.948

SLP III, p. 384, p. No. 194/40

Sung by: Franc Hribar (1908), Pavle Hribar (1909) and Franc Mlakar (1907); Recorded: 1968

Songs featuring such content are known among many European nations. In Slovenia we have two forms. In one of them the victim is the count’s page, in the other the count’s gardener. Whereas the first older from is represented by only two written records from the 19th century, the second form has remained preserved to these days in a poetic re-creation by Simon Jenko from the sixties of the 19th century. The verse pattern is the trochaic heptasyllable with anacrusis, combined in four-verse or two-verse stanzas. The melody likewise is in two or four lines, with the text, where necessary, adjusted through reiterations. The example chosen has two lines. In agreement with the manner of male polyphonic singing in our tradition every verse is started by the leading singer himself.

The present third audio publication, intended as a sound supplement added to Book III of the edition ‘Slovenske ljudske pesmi’ (SLP), Slovene Folk Songs, published by Slovenska matica, is at the same time an independent supplement illustrating the tradition of Slovene folk songs and bringing recordings of songs from two groups arranged according to content. First come legendary songs in which saints come up as intercessors or as persons ready to help people in various kinds of troubles. These are followed by songs speaking about retribution for virtuous life or punishment for vices, either in this world or in the world to come, as well as about the origin of pilgrimages and about events happening there. The next group is made up of narrative songs with social motives speaking thus of the oppression of feudal lords over their subjects, of opposition to love between people coming from different social strata, and transgressions against the uncodified law of the people, and so forth.

The order of the sequence of examples on the audio publication follows the order of songs in SLP 3. The book, published in 1992, contains 60 song types. For some of these songs the melodies are unknown, because the texts were written down already in the middle of the 19th century, when the collectors saw in the folk song only verbal art whereas the melody they either could not write down or it had already escaped the memory of old people. Although only a smaller number of types published in the book could thus be presented in sound, the 17 examples on the audio publication provide a good representation. In some cases two recordings of a particular song are offered so that the listener can see how a particular song is in its variants spread over several Slovene regions. Like all narrative songs these songs again do not differ from other kinds of song either in musical or formal respects, and also not in the way of singing. They may be sung by men or by women, or by both together, by young or by old people, by anybody knowing the song – at least for two voices, or preferably for three; some on various occasions, others when keeping vigil over a dead person (where and as long as this was the custom) but never simply for representation to listeners.

In content some of the songs draw on the commonly known legendary tradition, as it is also depicted on the fresoes in our churches. In many songs the conduct is judged from the viewpoint of Christian morality, so that the story is an unobtrusive way instructs what is proper and what is not. Although our ideas about the next world mainly agree with those held by other European nations, it does appear in places that folk imagination bursted out in our own way across the given framework. For some pilgrimage legends it may be said that there exist no models to be followed here.

As for songs with social motives it appears characteristic that they condemn wrongdoing but the afflicted leave the retribution to the supernatural force. In places it is to be noticed that in the shaping of the story elements of late mediaeval and of the Baroque mentality are intermingled.

dr. Zmaga Kumer