Slovenian Folk Songs IV: Narrative Songs - Love Songs

SLP IV, s.No. 203/14

GNI M 25.461

Sung by: Luigia di Floriano, Recorded: 1962

The motive of apparent death as a trick as used in folk tradition also appears in this ballad. Here, a lad pretends to be dead to court his beloved because all other methods have failed him. In most of the variants the story is transferred from the castle to a village environment, and its content is extremely condensed. This change must have been made rather early on, as in some variants the text still exists in the old tripartite octosyllable. Ballads with the same story are known among most European nations, in some cases they also exhibit formal similarities. In our Resian variant the apparent death, however, does not achieve the desired effect, and the text finished with the initial formula of denial. The text itself is in the Resian dialect, not translated into literary Slovene, and it is perfectly understandable. The example shows that the Resian song tradition is a constituent part of the common Slovene tradition despite its many different features. The song is based on a rising and falling melody. All the stanzas do not have an equal number of verses, the singers optionally prolong them so that the second part of the melody gets repeated as often as found necessary At the beginning of some stanzas even attempts at three-part singing are to be noticed. The song is made up of mere hexasyllables with anacrusis, which together with other elements, tells us that it is built on very old song patterns.

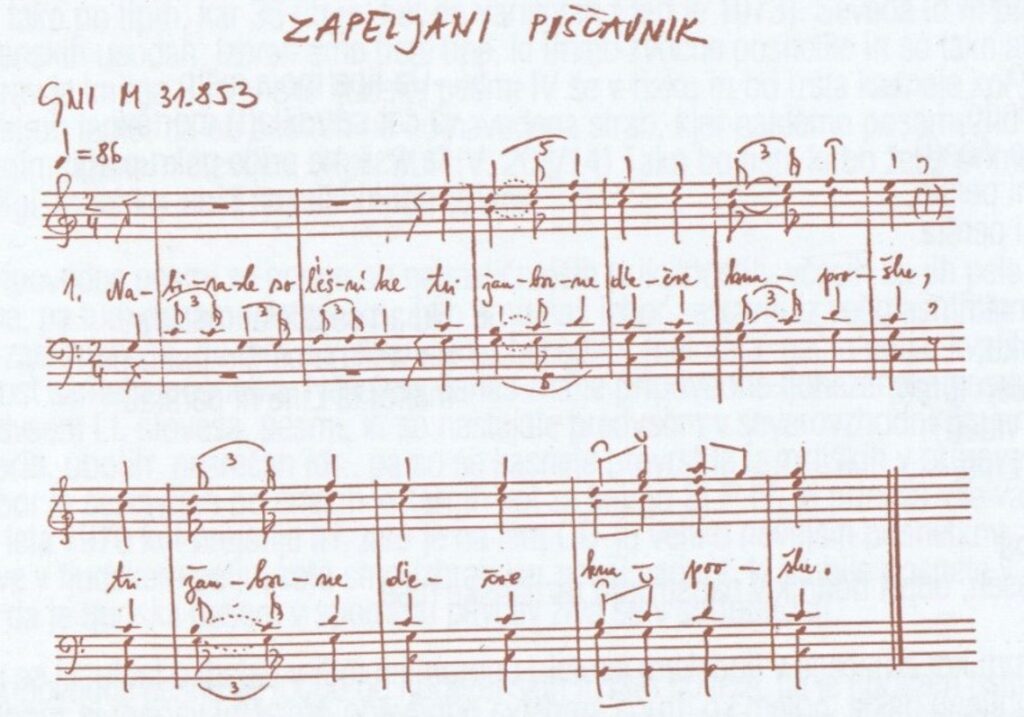

SLP IV, 206/5

GNI M 31.853

Peli: A group of singers from Zgornje Krčanje na Koroškem; Recorded: 1969

The song was recorded in Carinthia; most of the variants of this song come from the Austrian Carinthia. The story is abbreviated, but it nevertheless tells us how powerful the love of a girl is, powerful enough to seduce even holy men.

The musical basis of this song is fairly archaic, the song being made up of two-line stanzas where the first Imes are heptasyllables with anacrusIs, and the second, repeated, lines are three-part octosyllables with anacrusis. The melody as well is simple, both parts – the first one sung by the singer himself and the second with the group responding – are built on only three tones. At the end one might notice traces of the singing “on the third” .

SLP IV, s.No. 209/68

GNI M 44.484

Sung by: Rozika Ofič (1915); Recorded: 1988

The content of this ballad has its source in the German-speaking Slovene region of Kočevje. The song comes from the local variants of the German song “Jungfer Dörfchen” which was spread over all German regions and lived there to approximately the end of the 19th century. It belongs to the older part of folk song heritage, even if it was not written down before 1800. Slovenes must have become familiar with the variant from Kočevje at a comparatively early time, as we did not translate it but rather retold it in our Slovene way, but by means of the characteristics of the ballad design of the content (motives, pattern known in many other ballads). Also preserving thetrochean heptasyllable (4/3). It seems that already at the beginning the ballad was known throughout Slovenia,

as the earliest written records come from Primorsko, Styria, Upper Carniola, Lower Carniola. Already in versions written down before World War I, a form started to come up which replaced the original one, has become preserved to these days, and now classified among the most widely spread Slovene narrative songs. In this new form the shoemaker is still preserved, likewise his original name Anzel (a different name comes up only occasionally), the report of the sweetheart’s death is brief, anonymous (she does not need shoes because she has died), but then a new motive comes up: when on his walk, the shoemaker meets pall-bearers, stops them, and finds that the grave is lost and replaced by the formula before-now (e.g . last night wished good-night, today eternal light). The most change, existing also in our variant from Styria, is due to the transfer of the ballad into school class singing: the sweetheart has been replaced by Mummy (both of the original Slovene words, “ljubica” and “mamica”, have three syllables!); although in this way the content of the text loses its true sense, even grown-up singers are not disturbed by that.

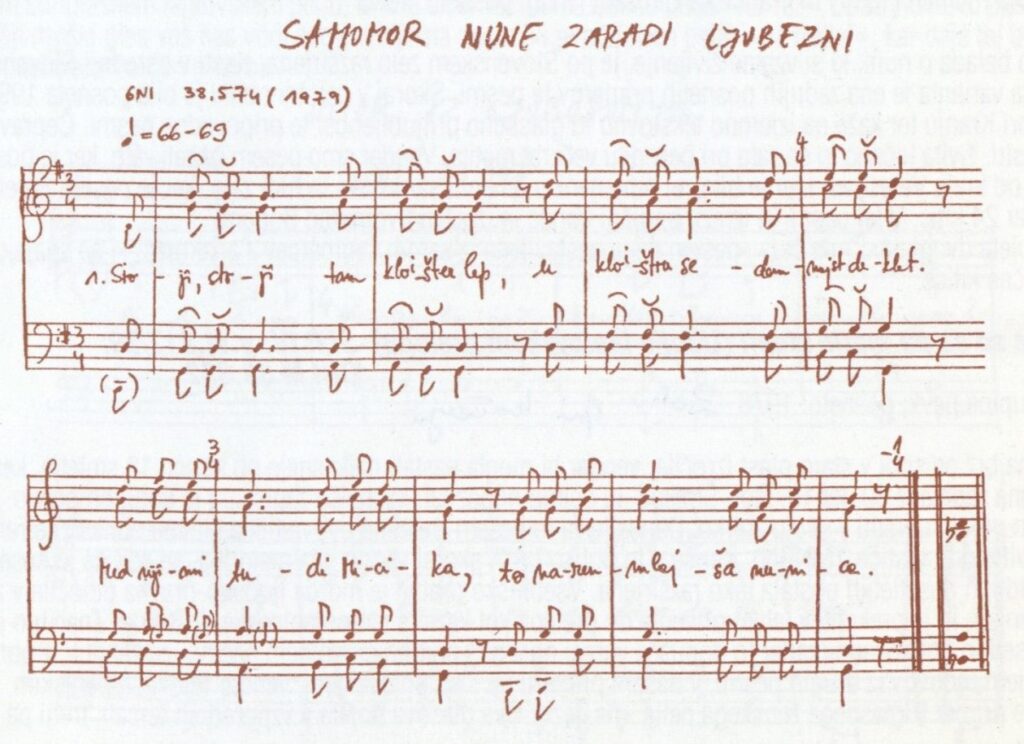

SLP IV, s.No. 215/132

GNI M 38.574

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded1979

This song can be found in Štrekelj’s collection. It can be divided into seven sub-types, but commonly in A-D. What they all have in common is the tragic fate of a girl sent to a nunnery by her parents against her will after she already had an experience of this world. In 1238 a nunnery was founded at Velesovo, which name is mentioned in most of the variants. The background of the song likely comes from the Middle Ages. It may be assumed that the song could have originated in the 16th century, judging by the soft monastic tendency expressed in the disapproval of the parents forcing the daughter already at an early age into the nunnery. Velesovo was a rich convent near Kranj, it had plenty of land, and it belonged under the Aquileian patriarchate. It was a place, above all, for daughters from the ranks of nobility, who brought their good fortune here. This was regarded as a special honour. But evidently not all of them thought so. A certain girl (Barbka, Urška…) in our variant Micika, must already have had a taste of love and was probably forced to go to the nunnery. In most of the variants the girl takes her own life because she would not to be let out; but in the present variant from Primorska the end is unusual: her mother-superior grants the request and allows her to leave the cloister. The end Is thus not tragic, but this Is an exception rather than the rule. The song, sung in four parts, consists of four- verse stanzas of heptasyllables with anacrusis.

SLP IV, s.No. 215/147

GNI M 46.344

Sung by: Pavla Pičman (1911) and Frančiška Cimžar (1912); Recorded: 1995

The tragic ballad about a nun who takes her own life is widely spread in Slovenia, especially in the central regions. The present variant is one of the last recorded examples of this song from Britof near Kranj. It was recorded in almost its entire form in 1995, and it shows how exceptionally popular this song was both on account of the text and of the melody. Although the singers are sisters, they live separated from on another and this accounts for their errors in the text. The song has been chosen because it originates not far from Velesovo, where the above-mentioned nunnery stood and because it was rendered in its entire length, in as many as 24 stanzas. This song has a clear tragic end and voices doubt about the existence of God.

The singers present the song in two-part singing called “über” (“na čez”) and it is made up of heptasyllables with anacrusis, combined into two-line stanzas.

SLP IV, s.No. 217/29

GNI M 39.332

Sung by: A group of female singers; Recorded: 1978

The song probably does not belong to the older tradition, but it might have originated at the latest towards the end of the 18th century, since the first two written records come from the 1930s. Štrekelj obviously did not know them, and later written records reached him too late to still be included in his collection. Currently, this song is characterised by a two-line stanza form with a refrain and repetition of the second line. Since this form is accompanied almost invariably by the same melody it seems that this song has become so widespread only in the last decades. The content is possibly derived from folk norms regulating nocturnal visits to one’s sweetheart when a violation of the rules could lead to a brawl as punishment on the part of village lads. It is characteristic that the text is shaped (when this is permitted by the verse pattern) in the traditional mode of expression, ie. through patterns, additions of motives from other songs, in our instance through comparison, but only in two degrees. The song is an example of three-part female “über” singing, called “na čez”. Two voices sing in parallel thirds, and the third one the “bass”.

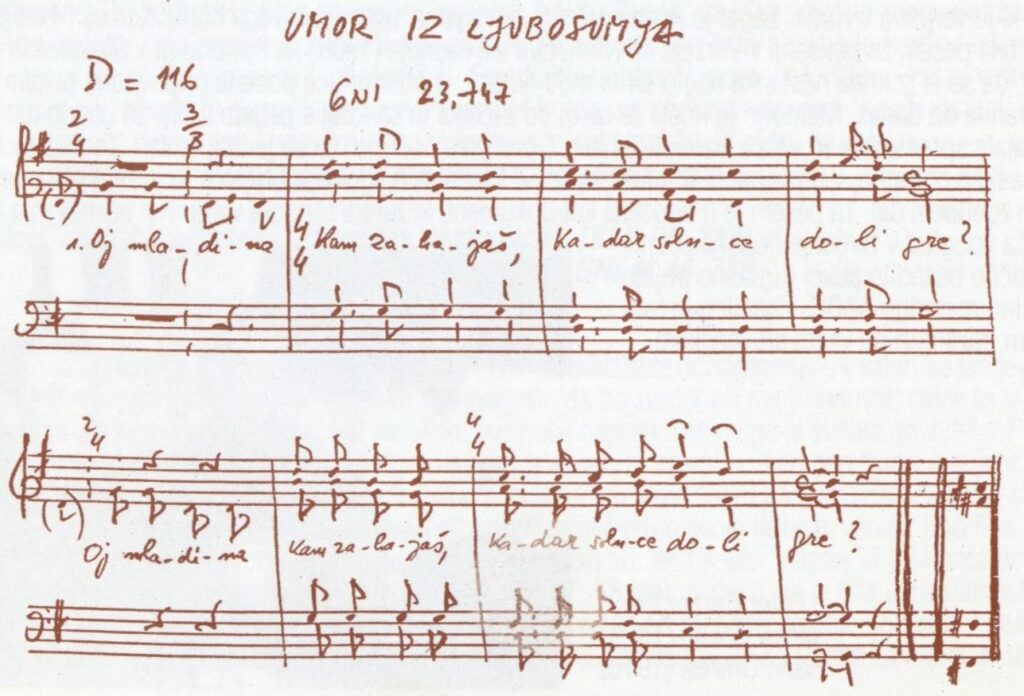

SLP IV, s.No. 218/64

GNI M 23.747

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded: 1960

This ballad originated as a memorial song of the kind that were once characteristic of northeastern Styria where it was (to as late as the middle of the 20th century) customary that on the occasion of some unexpected tragic death a song was composed describing the event in detail (with names of the persons involved, place, at times also the time). As regards the ballad “Killing out of Jealousy” it is interesting to note what particular singer from Mota near Radgona had to say in this connection, specifically that the murder had been committed in an inn near Kapela, when her daughter was still single. The boy’s name was Johan Fekonja. Since the woman was born around 1880, she could know the event only by hearsay, as the first written record comes from 1863. The murder might have taken place sometime between 1850-1869. A proof substantiating this assumption has not yet been traced in the registrar’s book. The song spread extremely rapidly in Slovenia. In the variants from Styria, Prekmurje and Porabje the boy’s surname, Fekonja, has been preserved but in other regions we find only “mladenič”, “mladenec” (youth). And in our variant from the Upper Carniola, he is a young army officer. The girl’s name Marija Rajhovka (or: Rajhova) is to be found only in variants in Styria, but elsewhere she had not named, and her age is between 20 and 22 years.

In this four-part male singing, for the most part in the “über” form of singing (“na čez”) we notice something particular. The highest male voice leads his line in singing “na tretko” (on the third) which imparts to the performance a special, archaic ring.

SLP IV, s.No. 218/99

GNI M 34.041

Sung by: Etelka Makoš (1915); Recorded: 1972

A proof that what was originally a memorial ballad is the great number of variants. It is characteristic that standard verses from other songs are also used here. While in the “original” the lad stabs the girl with a knife, in later variants (the present on being one of them) he cuts off the girl’s head, like in the ballad Brother to the Beloved One. In this song the name Fekonja is replaced by Francek, and the ending is interesting as the singer concludes this song from Porabje with an itinerant motive about two flowers, which after burial grow forth from the two graves and become twined together. This metaphorically denotes love that outlives even death.

The two-verse text in the pilgrim verse is sung on a tripart melody ABB’C. The song is interesting also for its alternating bi-, tri-and four-part rhythm.

SLP IV, s.No. 219/20

GNI M 28.279

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded: 1967

We can probably also establish the origin of this song type. In the year 1978, at Bute on Kozjansko, we recorded a song that is probably the original: It was sung by the son of the original creator, the murdered man’s brother. As soon as 12 years after the murder, the song was already written down at Veržej on the Mura, and two years later (1908) on Pohorje and at Slovenske Gorice. This shows that the song spread quickly from its place of origin. It is a song composed on the occasion of death and became a narrative song. As such, it has remained preserved until today. It had a melody already at the beginning and so kept spreading through transmission from person to person. In this way modifications have been made. In our variant, which is from Upper Carniola, we can see that the name of the boy, Tonček, and of his native village are still preserved; in this variant the singers have omitted the punishment for the boy’s murderer, and therefore only the basic part of the story is preserved. This song is precious as a document which through many variants and through a knowledge of the original permit insight into the life of a folk song

The text of the four-verse stanzas is sung three parts on a tripartite melody AABC. Characteristic is also the 5/8 rhythm known all over the Slovene territory.

SLP IV, s.No. 220/59

GNI M 23.948

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded: 1960

This type of song shows us traces of mediaeval legal norms that are contained within the song. The girl, who makes a decision for her brother instead of for the beloved one, acted in accordance with the rules of her society. These rules made it possible for the brother to have over his sister, if she became a widow, and over her children, complete authority (avunculate) and even to choose a new husband for her. According to the norms of that time, blood relationships were stronger than a relationship established by feelings, for the girl knows that a brother is irreplaceable. It is interesting that despite the sad story the refrain is vivid and gay.

SLP IV, s.No. 221/140

GNI M 45.841

Sung by: A group of male singers from Zagradec, Recorded: 1990

The song type The Faithful Girl – the Sweetheart can be divided into four sub-types: (soldier, army officer, boy, man, even partisan). The story in the song is a test of the girl’s genuine love urging her to become his girlfriend, for he claims to have witnessed a boy’s death. When the girl remains steady in her first love, saying that she will be in mourning for the dead boy for seven yeras, her lover reveals himself. Considering the details in some of the variants it can be said that this well-known song is part of the older, possible even later mediaeval tradition. The song is widespread throughout Europe in many forms. In Germany, for example, it is known under the title “Liebesprobe” – A Test of Love, but it is known almost by all western nations as well as in a large parts of eastern and southern Europe. The song concludes with a happy meeting. In our variant, the singers sing about the girl’s words that she had given the little bunch of flowers to her boy before he went to war. The song is a very fine example of determined male four-part singing, called “über” (“na čez”).

SLP IV, 222

GNI M 46.735

Sung by: A group of male singers; Recorded: 1996

According to its content, the core of the ballad is probably taken over from the German song “Der schwatzhafte Junggeselle” in which lads gathered in a local inn are talking about their sweethearts. One of them boasts that in the evening he will visit his sweetheart. The girl overhears this, runs home and locks herself in her room. When the boy comes and knocks on her window, she refuses to open it for him, saying that she had heard him say he would visit her. The first written records of this ballad come from the 16th century. The song is known throughout the German-speaking territory, as well as among German emigrants elsewhere in Europe, in Holland, Denmark, and France. The earliest Slovene written records about the song are from the middle of the 19th century and are surprisingly close to the German original, for here as well lads praise their sweethearts but under a linden tree and not in an inn, the place is Vinavas, Zavogle, Voglajna. It is only in written records that we learn that that the content of the ballad must have reached Slovenia already in the 17th and 18th centuries, at a time when folk creativity was still considerably alive. This is way it could be made into a Slovene song through its details and stabilised through the transfer of the action under a linden tree in Ljubljana. This is probably “the song about a linden tree on the old square” which was written down by Dizma Zakotnik around 1775, although the written record itself got lost. Our example is the most recent one. It was recorded in 1996 in Lower Carniola. Additionally interesting is the fact that the song was sung by lads late in the evening, and crickets can be heard, which conjures up the genuine atmosphere of folk singing.

SLP IV, s.No. 225/57

GNI M 24.222

Sung by: Matija Koštric and Jože Cigan; Recorded: 1961

According to the earliest written records, the song must have originated at least in the 18th century, if not earlier, and still belongs among narrative songs still popular today. It seems that soon after its origin it spread all over Slovenia, during which the two names fell into disuse, since they have a somewhat strange effect, which suggests an artificial source. This ballad is taken from real-life scenarios and does not tell anything exceptional. In the not-so-distant past many a student became a priest through the wish of his parents, although he did not feel the real inclination for this profession. In the song the renouncing of love for the sake of priesthood is stressed to a tragic point. In some variants the text takes the stanzas (probably artificial, sentimental ones) of a song about the unexpected death of the sweetheart and about the boy’s grief over it soon after the opening. It is interesting to note that a specific way of the shaping of the text of folk songs has prevailed over reality and so in some variants the transsubstantiation, for instance, is mentioned up to three of four times, although folk singers know that in the course of the mass it happens only twice. Something similar is with the choosing of the girl’s clothes for going to new mass, with the intensification of weakness to the very death, and generally with the use of stylistic patterns, irrespective of possible illogical combinations. In this variant the singers have also added the pattern of flowers growing out of the graves and then twining together, which points to the strength of love. On the formal side there is an interesting case of the so-called itinerant verses. From a musical point of view, the song is interesting because of its almost pure pentatonic nature, which is also otherwise fairly frequent in songs from this region.

SLP IV, s.No. 225/84

GNI M 41.569

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded: 1983

Our variant is condensed and tells only what is essential: that the boy has broken the promise he gave to the girl but kept the promise he gave her mother. The singers conclude their song by singing that the student’s love is deceptive. The superimposed moral is of a more recent origin, and the singers have omitted the

celebration of mass and the death of them both.

The song is an example of mixed male-female four-part singing in which women sing the leading and the accompanying part, and men the bass and the so-called “vmes” (in-between).

SLP IV, s.No. 227/19

GNI M 24.281

Sung by: Marija Šimen (1912); Recorded: 1961

The historical basis for this song can probably be traced to the 30 Years’ War (17th century). We may conclude from the young man’s outfit (the plumed hat worn at that time by officers) that the song originated in the 17th century or later. In our version, from Prekmurje, these historical traces have been lost, and for this reason in the middle of the song the act of chopping off the unfaithful sweetheart’s hand is a dramatic detail.

In this example, it is obvious that the singer is accustomed to singing the accompanying part, which is a proof that the song was certainly sung by a group.

SLP IV, s.No. 229/13

GNI M 24.550

Sung by: Franca Rosulnik, Recorded: 1961

An example of a love ballad where there is so little of the story that according to the text it could easily be a usual non-narrative love song, in particular because Slovene love songs contain a great many narrative features. The concluding stanza of some variants (what is meant by the ring, and what by the crown) is not essential, possibly a later addition, but the content suggest that the song originated in a moralizing environment and as such belongs to a younger layer of the tradition. The only recording kept in the archives came from Selo near Vodice; it speaks in a very light way of the girl’s penitence.

This melody is also of an accompanying type, and it is interesting because of its exceptionally narrow range of altogether three neighbouring tones.

SLP IV, s.No. 230/41

GNI M 33.752

Sung by: A group of singers; Recorded: 1969

Štrekelj published the variants of this song among narrative songs. Here, again, they have been classified as such. Yet these songs are already strongly changed, and one can hardly speak of narrative structure any more. The centre of the content is also shifted over to death itself, so much so that the song, in content and in function, comes close to a memorial song. Despite varying regional sources, at least central Slovene variants have a great deal in common. The spread and the similarity is probably due to the fact that the song was published in St. Mohor’s calendar for the year 1897.

As example of two-part singing the Venetian region with the very common refrain on syllables jo – la – li – le found there, etc.

SLP IV, s.No. 230/52

GNI M 34.032

Sung by: Ana Borovnjak (1913); Recorded: 1972

Variants of songs from Porabje and Prekmurje are distinctive, not only as regards the language but also content, so much so that they could represent an independent type of song, The Sick Sweetheart Dies. The focus is mostly on the theme of love. On the contrary, central Slovene songs point out the motive of death and burial. But it is also true of the variants from Porabje, hence also of the present example, that they are

probably already in a curtailed form, or rather that they are on the transition from a narrative song into a lyrical one.

SLP IV, s.No. 232/25

GNI M 24.886

Sung by: Janez Šinkovec; Recorded: 1961

As concerns content, this song is related to carriage services, which flourished in Slovenia from about the 15th century to the second half of the 19th century, when traffic shifted to the railway. Considering its first publication in 1839, it may be assumed that the song originated at the latest towards the end of the 18th century. The emphasis of the content is on the death of the two lovers, which leads to the motive of flowers growing out of the grave. In some variants this occupies the largest part of the text and so Štrekelj used this even as a title, or respectively as a designation of the song’s content. Our example is interesting because it differs from other songs in its end: when the boy asks the girl what is wrong with her and why she is ill she answers to him that she had herself condemned her son – she murdered him. This is an unexpected reply and might have been picked up from the song The Bride-Child-Murderess as an itinerant verse.

SLP IV, s.No. 235/18

GNI M 30.347

Sung by: A group of male singers; Recorded: 1969

This song is of recent origin, thus it is to be found neither in Štrekelj nor in the collection Sto Žalostnih (One Hundred Sad Songs). It is probably based on a certain true event, as in all the variants right to up to today the names of the two chief figures, Olgica and Branko, have been preserved. The tragic end is not so poignantly dramatic as in other ballads: in our case the end is not tragic at all – for the girl has decided, despite her sorrow, to re-marry. In this case we come across a truly old way of singing, characterized mostly by a very slow, prolonged way of singing which is mentioned by our older informants as a way “in which it used to be sung in the old times” and also by pentatonics “on the fourth”. Because of otherwise stronger middle voices this part is not so well heard, but it can be followed with an attentive ear.

SLP IV, s.No. 236/16

GNI M 45.241

Sung by: Marija Škrinjar (1903), Recorded: 1989

A more recent narrative song, originating probably at the end of the 19th century, since the first written records of it are already from the 20th century. The strophic form (8787) and the almost invariably similar melody point to an artificial source, but the author remains as yet unidentified. This song is changes in the text, and its popularity, especially among women-singers, is shown by its spread through various places in Slovenia.

Slovene Folk Songs:

Narrative Songs – Love Songs

The series of compact discs based on the collection From the Archives of the Institute of Ethnomusicology is titled Slovenske ljudske pripovedne pesmi IV (Slovene Folk Narrative Songs IV) and is now continued with the fourth audio publication of narrative love songs. The present audio publication is intended as a sound complementation to Book IV of the collection of Slovenske ljudske pesmi (SLP), (Slovene Folk Songs) but it may also be regarded as an independent publication with its own accompanying commentary.

The fourth audio publication brings a selection of 21 narrative love songs, which beside legendary and family songs are most numerous as regards both types (as many as 36) and variants (1073 of them). This is of course not surprising as they deal with love and its fate. We have chosen those types which are featured on sound recordings and are in one sense or another interesting to be published. Although Book IV is still in print and will come out later than the audio publication, it has been decided, despite the fact that along with the song the page will not be given where a particular song is to be found, to mark the song with the type and number. (e.g. SLP: 203/14). In this way, somebody wanting to compare the selected variant with others in the book will be able to do this when the book has been issued.

Narrative love songs are sung on most various occasions; at times they were sung by young male groups, or by mixed groups, and also by individual female singers. Our selection has therefore included songs for both multi-part, two-part, and one-part singing. We have opted for as much regional representation as possible, our selection based on whether the text, the melody, the way of singing, the quality of the recording is interesting, or whether the variant is the only available recording of the song. Some of the currently-known narrative love songs used to be sung by the side of a dead person lying in state, above all the so-called farewell songs, while song originating predominantly in North-Eastern Styria, occasioned by tragic events such as murders or manslaughter’s, disasters and so forth, changed from songs sung at a death to narrative songs, e.g. the song “Murder out of Jealousy.” The selection here follows the same criteria as applied for the book SLP IV, which includes all the variants till 1996 and not merely to 1970, as is the case with the first three books. As such, the present audio publication has a great many more recent recordings to offer. Some of these songs are still heard today when people come together and sing. We have therefore included quite a few variants recorded in 1995 or 1996, which testify that the folk song is still alive in the memory of its singers in our own times.

Narrative love songs are distinguished from lyric love songs by the fact that in the former, love represents that feeling which leads to the conflict in the story, whereas in lyric songs the feeling itself is in the foreground. The selection follows the content pattern, which presents love as a strong, acting feeling, mostly even a highly tragic one, understandably influenced by most varied of life’s circumstances causing “a dramatically emphasized event, a story”.Therefore such songs are also called love ballads. The dramatic course of events contains personal feelings which may get lost behind a more emphasized story or the protagonist of the action. The protagonist is most commonly an impulsive figure, expressing his passion directly, and these turn out for him fateful, at times even tragic. The nucleus of the story in the poem is the hero’s action that calls forth a happy or unhappy act of love and its consequences. The motives for such an action are in most cases only briefly outlined. In accordance with the brevity of expression in the folk song, the reasongs for the motives are blurred. Also among narrative love songs belong love ballads and songs that have preserved a dramatically emphasized event, which, however, has been curtailed. The classification of songs according to content thus follows the logical course, a mutual relationship. Accordingly, our songs begin with courtship, are continued with unhappy love, with murder or manslaughter out of jealousy, and conclude with infidelity, with death out of love.

dr. Marjetka Golež, mag. Robert Vrčon