The Echo of the First Recordings

Recorded: Tišina, Prekmurje, 1898.

Sung by: Anuška Horvat.

Archived at the Folk Music Department at the Musicological Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

The song “Marko skače, Marko skače” (Marko Leaps, Marko Leaps) is the ninth of 13 songs that the Hungarian researcher Béla Vikár recorded in the village of Tišina in Prekmurje in 1898. It was a courtship song, and it remained part of living memory in the Raba River valley region with its original dance form until the 1970s; the playful dance with the selection of a dance partner was added in Beltinci before the Second World War. The song is also known beyond Prekmurje and the Raba River valley, in the entire area along the Slovenian-Croatian border. The similarity of the Slovenian and Croatian variations most probably does not stem from interethnic contact, but reflects an older, common cultural layer.

Recorded: Bled, Upper Carniola, 1913.

Sung by: group of young men

Archived at the Institute of Russian Literature,

Russian Academy of Sciences (Pushkin House).

In September 1913 the Russian collector Evgeniia Lineva (a.k.a. Eugenie Lineff) recorded some 100 Slovenian songs in Bled, Rečica, and Brezje in Upper Carniola, as well as in Adlešiči and Vinica in Bela Krajina. The recordings from Bled include young men’s and men’s part-songs from the region in three and four-part harmony, which disappeared from the area after the Second World War. The love song “Jaz sem si pa jeno zmislu” (I’ve Thought of Something) was recorded with multiple voices; the “horn” of the phonograph had difficulty in capturing the individual voices, as evidenced by the quality of the recording.

Recorded: Preloka, Bela krajina, 1914.

Sung by: Peter Radovič, Jože Radovič, Jože Starešinič, Ive Požek, Marica Starešinič, Magdica Starešinič, Frančiška Starešinič, Bara Starešinič, Jela Radovič and Mara Žunič.

Archived at the Institute of Ethnomusicology of the ZRC SAZU in Ljubljana.

Juro Adlešič, a lawyer from Bela Krajina, recorded 38 songs on 31 May and 1 June 1914 in his native village of Adlešiči and in Preloka on a wax-cylinder phonograph, including “Tri jetrve žito žele” (Three Sisters-in-Law Were Reaping Grain). This is originally a love song, and variations that begin “Three girls were reaping grain” are known in Croatia as far as Dubrovnik as well as in Bosnia and Serbia. Because this recording refers to sisters-in-law, it is difficult to view it as a love song. The recording does not contain the additional verses transcribed by Niko Štritof. The song is also noteworthy for its unusual harmonic seconds.

1. Three sisters-in-law were reaping grain,

Ladole dear,

Three sisters-in-law were reaping grain,

Oh, Lade mine.

2. The first reaped, reaped one sheaf …

3. The second reaped, reaped two sheaves …

4. The third reaped, reaped three sheaves …

5. They remembered among themselves …

6. Who would choose which boy …

Recorded: Judenburg, Styria (Avstrija), 1916.

Sung by: A group of men

Released on Nr. 26, PH2542, iz: PHA CD 11, Gesamtausgabe der historischen Bestände 1899-1951, Serie 4: Soldatenlieder der k.u.k. Armee, CD 2.

On the initiative of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War, the Viennese Phonogrammarchiv and its assistant (and later director) Leo Hajek made recordings of the singing of soldiers from all the nations of Austria. The Slovenian songs, recorded in Radkersburg and Judenburg, are among the most moving of these sound recordings. The song “Oj ta vojaški boben” (Oh the Military Drum) was recorded on 20 March 1916 as sung by Slovenian soldiers in Judenburg. This was the seat of the replacement battalion of the 17th infantry regiment, which included soldiers from Carniola. The song expresses the basic character of Slovenian military songs in that it is not heroic, but melancholy for the most part. The Slovenians were not fighting for their own authorities, and the attitude toward military service was therefore a negative one. At the time of this recording, nobody could have guessed that Judenburg would prove to be the site of the largest mutiny by Slovenian soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army.

GNI M 30.043

Recorded: Ljubljana, Upper Carniola, 1958.

Sung by: Franc Kramar, Matena near Ig, Inner Carniola.

The song of Pegam and Lambergar, which tells the story of the duel between Gašper Lamberg from the castle at Kamen near Begunje and Pegam, a giant of superhuman strength, was first mentioned in the 17th century. Jožef Zakotnik’s transcription from 1775 has been lost. Although it is a later transcription, Franc Kramar’s recording of the song, sung for him by the day-laborer Katarina Zupančič (Živčkova Katra of Vinje), is of exceptional importance, as it is the only transcription with a melody. Kramar sang the song from memory at the Institute of Ethnomusicology, but only the first stanza was recorded of the 30 that he wrote down while listening to Živčkova Katra in 1910.

GNI M 45.777

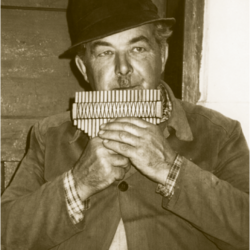

Recorded: Jablovec near Podlehnik, Styria, 1990.

Played by: Franc Laporšek.

Boys – especially shepherds with their flocks, but also adults – played the panpipe, a folk instrument with tubes of various lengths. For the most part they played only the melodies of songs. The panpipe tradition was likely inherited from earlier settlers and is represented on the Vače situla. Some individuals in Styria – such as Franc Laporšek – continued the tradition of making panpipes even after the Second World War.

GNI M 24.480

Recorded: Preloka, White Carniola, 1961.

Sung by: Anica Spišič, Marica Starešinič, Kata Starešinič and Angela Starešinič with Franc Grdun (double whistle).

At the time of the first sound recordings, songs for Midsummer Day celebrations were the oldest songs preserved in Slovenia. They had strictly ritual connections and their ancient character is expressed both in the style of singing and in the melodies; later Christian influences can especially be seen in the lyrics.

Young women, known as kresnice, would depart from the Midsummer bonfire to sing songs to bring fertility to the fields, vineyards, people, livestock, and bees. Four or six would walk together, divided into two groups. They were accompanied by a piper, who in the 19th century played the diple (a bagpipe with two pipes), and later the dvojnica (double whistle). Traditionally his playing had no rhythmic or melodic connection to the song. The group was accompanied by a young woman that carried the gifts they gathered, usually eggs.

The kresnice sang antiphonally by alternating the singing between the two groups, and would “overtake” or “chase” each other: each group would begin singing before the other had finished its part.

The ritual strictly forbade them to stop singing while walking among the houses, fields, and vineyards. The Midsummer song selected for the audio publication is one of the musically oldest among those preserved: the lyrics are those sung where there was a young man in the house. It has the shortest melodic line and preserves ancient two-part singing with a drone bass.

GNI M 20.250

Recorded: Žaga near Bovec, Littoral, 1957.

Played by: Bovec musicians.

In specific areas celebrations were very much marked by groups of musicians. The Bovec musicians from Žaga were one such group that traveled around much of Slovenia as well as abroad. They were able to alternate roles because they played two or three different instruments apiece. Because they played in widely separated areas, they had to master an assortment of dance melodies. They thus brought dances from elsewhere into the Soča River valley, which people danced and gave their own names to. The cvajšrit (two-step) in this recording was danced in the Upper Soča River valley with ordinary steps and then turns to the right or left or with a buoncing motion.

GNI M 33.817

Recorded: Bovec, Littoral, 1971.

Sung by: Franc Pristovnik, Pepi Oražej, Hanzej Roblek, Lojze Kelih, and Florijan Kelih, Sele/Zell Pfarre, Carinthia (Austria).

When folk culture was at its height, singing in the village preceding the traditional vasovanje serenading was typical among groups of young men. After the Second World War – either because of forced or voluntary departure to the factories, or because of changes in lifestyle and social relations – this gradually died out, remaining a living tradition in places until the 1970s.

The example on this recording is typical of the part songs that remain very much alive in Carinthia today. One of the singers sings the lead (called naprej), a second sings a third higher (prek), a third sings higher yet (na treko), and they are accompanied by a bass. This singing style is referred to by various names.

GNI M 22.309

Recorded: Podvolovljek near Luče, Styria, 1958.

Recited by: Janez Golob.

The so-called “goat’s prayers” – used by young men to address young women after group singing – are proof that the rhythmic character of a set formula could also help someone in a fix. Such formulas were handed down from generation to generation within groups of young men. More timid young men were assisted by “skilled lovers” (plavšmajstri) – experts that helped them court young women.

GNI M 21.708

Recorded: Podkoren, Upper Carniola, 1958.

Played and sung by: Emil, Fric, and Lojze Razinger, Tone Mertl, and Jože Pečar.

The štajeriš is a courtship dance that took shape in the eastern Alpine area. In Austria it was known by at least the second half of the 17th century and, judging from the account of a dance in the 1689 work The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (turning of the female dancer, who holds her partner’s hand in one hand, raised above her head), it was most likely also known in Upper Carniola.

The original form of the štajeriš, as the selection also illustrates, was two-part: while couples walked in a circle, individual dancers would usually sing improvised quatrains – humorous love songs known as poskočnice – and after each one they would dance to an instrumental variation on the song’s melody. They were sung individually; group singing, as heard in this example, was unusual. In some places the štajeriš operated as a popular forum: through singing they were able to express what they otherwise hesitated to say aloud. As a song and dance form in Slovenia, the štajeriš was preserved longest in Carinthia, in the Upper Sava and Upper Savinja River valleys. Otherwise it was danced – without the sung poskočnice – throughout Slovenian ethnic territory, except in Resia. It has remained a part of popular tradition to this day.

GNI M 24.172

Recorded: Črensovci, Prekmurje, 1961.

Recited by: Jože Cigan.

Everyday life in the countryside was filled with set phrases and calls, and these calls were especially important for announcing the arrival of special visitors, primarily peddlers. The arrival of the kupinár – who dealt in poultry and eggs along the Mura River valley – was announced by a special call. In it one can hear the beginnings of voice register changes, similar to yodeling. The kupinárji learned these calls in secret. This recording also illustrates this phenomenon in dialect.

GNI M 30.026

Recorded: Velika Varnica, Styria, 1969.

Sung by: Gizela Kozel, Marija Kranjc Sr., Anka Vidovič, Marija Kranjc Jr., and Marija Emeršič.

In the postwar period narrative songs were still fully alive, including those whose historical origins had faded. Such is this song, originating in an example given from an early Christian pulpit; it seeks to show that through repentance and lifelong penance even the worst sinner can achieve forgiveness and eternal salvation. The memory of the time when the Slovenians lived near the Danube shows that this heritage was handed down to the Slovenians in the 8th or 9th century – that is, in the age of conversion to Christianity when lifelong penance was still practiced in the Aquileian Patriarchate.

The singing of Haloze, which is presented in this song, is also interesting from the musicological perspective. The discovery of a strong center of this old type of part song in Haloze shows that young men’s songs for four or five voices – which was considered a regional specialty of Carinthia – is merely an older style of singing part songs that must have once dominated the entire central area of Slovenian ethnic territory.

GNI M 25.458

Recorded: Liščace/Lischiazze, Resia (Italy), 1962.

Sung by: Luiga di Floriano and Ana di Floriano.

The song of Beautiful Vida has a special place among Slovenian narrative songs, especially because of the poetic reworking of the original song by France Prešeren and because of the symbolic value it acquired in its representation by the novelist Ivan Cankar. The true value of “Beautiful Vida” can be felt directly in the folk song, made possible only by its discovery in Resia in the 1960s. A fragment of the song was also still alive at that time in Dane near Ribnica.

This variation of “Beautiful Vida” from Liščace in Resia is the first sound release of the song. It is the simple and tragic tale of a young mother that sets out in a boat to search for a magical root to relieve her child, but the sailor sails the boat astray. Vida asks the moon, stars, and sun if they have seen her husband and child. Through each of them she hears how the separation has afflicted both her husband and child, and each time she helplessly cries out to the sailor that has separated them “Evil befall you, sailor …” (Hüdo ti bodi, mernor…). Vida feels neither guilt nor regret, but only intense longing for her home and awareness that a great wrong has been done to her family. Tetratonic and pentatonic songs were known throughout the Slovenian lands, especially in border areas, and some ritual songs also have this character. The pentatonic melody of “Beautiful Vida” with its introduced semitone (c) likely shows a transitional stage from pentatonic to diatonic, as well as a connection to ancient three-note or four-note melodies.

GNI M 40.325

Recorded: Bila/San Giorgio, Resia (Italy), 1982.

Played by: Giovanni di Lenardo and Giuseppe Clemente.

The music and dance of Slovenians in Resia have their own character. The citira (a higher-tuned fiddle) and the bunkula (a three-stringed bass) form a characteristic and simple instrumental combination. The melody – known in Resia as a viža or vižica – is clearly played in two parts: the musicians alternate between na tenko (the tonic or keynote) and na tolsto (the subdominant, a fifth lower), concluding with the cvik (a high glissando on the citira) and cvak (a stroke on the open strings of the bunkula).

This music was of great importance for a dance in Resia, which was performed by couples, although the dancers never touched each other. Instead, they danced past each other from opposite starting points, continually changing these points. The dance melodies are in alternating 3/4 + 2/4 time (as in this example) or in 2/4 time. The end of the melody on the tonic was marked in the dance by the man stamping on the floor and the woman making a similar movement.

GNI M 26.580

Recorded: Zagorica in Dobrepolje, Lower Carniola, 1964.

Recited by: Ančka Lazar.

Before the Second World War incantations, such as this one against snakebite, were a widely used method of treatment in folk medicine. People believed that the incantation could only be known by one person, or it would lose its power, and incantations were therefore handed down only by the very elderly.

GNI M 37.992

Recorded: Kazaze/Edling, Carinthia (Austria), 1977.

Recited by: Marija Gaser.

Incantations, such as this one against the skin disease lichen planus, retained their value as old ritual formulas even after their original meaning had been almost completely forgotten. The incantation was accompanied by specific ritual actions or the use of home remedies. For example, lichen planus was treated with an application of residue from a tobacco pipe after the incantation.

GNI M 25.547

Recorded: Zagorica in Dobrepolje, Lower Carniola, 1963.

Sung by: Ančka Lazar.

The custom of holding wakes for the dead preserved a large number of narrative songs, sung alongside songs about death and passing away. These songs

preserved a Baroque symbolism and sense of equality that could not be changed by wealth: the conviction that after death the master lies alongside the beggar (petler) helped people overcome their everyday misfortunes. This type of song largely moved from the religious to the folk context, which is also shown in this song by its structure and moderate triple meter.

GNI M 21.930

Recorded: Imovica near Lukovica, Upper Carniola, 1958.

Recited by: Marija Petek.

The praying of the golden Paternoster, an apocryphal narrative of the sufferings of Jesus, was believed to hold special power. This “Slovenian folk passion” was thus popularly preserved in various forms even long after the Second World War, either as an evening or Lenten prayer.

GNI M 34.427

Recorded: Šentvid pri Stični, Lower Carniola, 1973.

Rung by: Janez Bijec Sr., Janez Bijec Jr., Andrej Vencelj, and Anton Vencelj.

Change ringing – the rhythmic striking of a song on bells, in which the individual voices follow one another in the melody in a strictly defined order – is a special part of Slovenian folk music. The bells, which are otherwise used for regular chiming, are struck directly by the bell ringers, and their harmony creates a very festive atmosphere.

GNI M 29.337

Recorded: Črni vrh/Montefosca, Venetian Slovenia (Italy), 1966.

Sung by: Mjuta Lavrenčeva, Kal/Calla, Venetian Slovenia (Italy).

This old Easter song has been preserved in Slovenia’s folk heritage for an exceptionally long time. It also appears in old manuscripts, including the Stična

manuscript from the 15th century and Reformation era Protestant hymnals (with modified lyrics), as well as in later transcriptions. It has been recorded as a folk song in various parts of Slovenia, and after the Second World War it was preserved as part of a special custom in Kropa in Upper Carniola. It was preserved longest in the extreme western part of Slovenian ethnic territory, in Resia in Venetian Slovenia. The song’s age is also indicated by its preservation of a chorale melody.

GNI M 22.968

Recorded: Palovče near Begunje, Upper Carniola, 1959.

Played by: Anton Štular.

The diatonic accordion appeared in Slovenia in the second half of the 19th century, earlier in some places, later in others. As a musical instrument it quickly displaced the quieter dulcimer, and in the 20th century it assumed the leading role in folk music groups. It was also suited for dancing when there were no musicians playing other instruments, especially at parties after a group had worked together.

Alongside the štajeriš, the zibenšrit (seven-step) is the most widespread dance in Slovenia. As the name indicates, it is German in origin: the number of steps being seven probably once had some magical significance. As a couple’s dance with a recognizable dance form, it was danced similarly in all Slovenian regions and its choreography changed little.

GNI M 26.387

Recorded: Sušje near Ribnica, Lower Carniola, 1964.

Sung by: Alojzija Lovšin.

Drought represented one of the worst threats to farmers, and they turned to supplications or prayers for rain as the only recourse within their power. Despite the Christianized form of these supplications, their magical significance was apparent in many places even at the beginning of the 20th century. People went to sing them at specific places, for example at bridges, and sometimes they were only sung by young women.

GNI M 25.063

Recorded: Selo pri Vodicah, Upper Carniola, 1962.

Recited by: Franca Rosulnik.

This supplication to ward off a storm is an interesting interweaving of pre-Christian and Christian beliefs: the pre-Christian manner of influencing supernatural

forces is supplemented with fully Christian symbolism. This formula against storms (huda ura), recorded here only once as an example, was repeated three times in actual practice.

GNI M 31.339

Recorded: Gornji Senik/Felsőszölnök, Raba/Rába River valley (Hungary), 1971.

Sung by: group of women.

Old nuptial customs were preserved at traditional weddings long into the postwar period, including certain songs customarily sung at such occasions. Such a song is the humorous epithalamium “An Ant Drove to the Mill,” in which the cares and joys of the wedding party are expressed in images from the animal world.

GNI M 32.308

Recorded: Beltinci, Prekmurje, 1970.

Played by: Janez Kociper, Jožef Gruškovnjak, Tinek Maučec, Jožef Kociper, Mihael Nemec, Anton Bakan, Martin Bakan, and Miško Baranja (Kociprova Banda).

In Prekmurje a group of musicians was called a banda. It was generally comprised of string and wind instruments, and could be joined by a cimbalom, and later a piano accordion. The group was usually named after the lead fiddle player, or primaš. This is how the Kociprova Banda of Beltinci – which performs in this recording – was named. Such groups primarily played at wedding parties, known as gostüvanje. For nearly half a century, starting in 1939, the Kociprova Banda accompanied the Beltinci folklore ensemble at performances. Their program preserved the majority of folk dances that were customary in the Ravensko and Dolinsko regions of Prekmurje.

“Gentleman-Lady” is a Prekmurje variation of a dance of Austrian or German origin that is found especially in Upper and Lower Carniola, where it is known as nojkatoliš (“new Catholic”). In Beltinci it is also called the “Prekmurje star” (prekmurska zvezda) because couples would dance from an outer circle toward an inner ring and back.

GNI M 25.304

Recorded: Kropa, Upper Carniola, 1962.

Sung by: Valentin Šmitek.

This carol from Kropa is actually a song based on a play. Caroling at Christmastime has a long tradition reaching back to the medieval period. In his catechism of 1575 Primož Trubar mentioned that “carolers sing about Christmas.” In the baroque era these were combined with scenes staged in churches depicting the arrival of the shepherds and their adoration of the newborn Jesus. During the Jansenist period these plays were forced out of the churches but were preserved in people’s homes. They continued longest as carols in areas associated with iron-working: in Tržič, Kropa, Železniki, and Kamnik. In the winter blacksmiths were idle, because they could not use their water-powered forges while the water was frozen. At the end of the 19th century Christmas caroling was generally combined with caroling for New Year and the Feast of the Three Kings. The memory of the custom, such as in this song, remained alive in places even after the Second World War.

GNI M 22.547

Recorded: Luče, Styria, 1958.

Recited by: a girl.

Spoken rhythmic texts known as tepežnice used to (and in some places still) accompany ritual thrashing on the Feast of Holy Innocents on 28 December. Beating with a switch was a magical act meant to bring fertility and to transfer the vital force from plant to man. Originally adults did the thrashing, especially young men. Later, when the custom lost its original significance, it was seized upon by children, who thus took their revenge once a year for the cuffs they had received.

GNI M 47.954

Recorded: Slovenja vas, Styria, 1998.

Played by: Robi Butulen, Miran Selinšek, Tona Širovnik, Vlado Jurgec, Darko Kos, Ivan Kirbiš, and Branko Kos (Lancova Vas Folklore Society), Lancova Vas, Styria.

The mazurka originated as a Polish folk dance that in the first half of the 19th century spread across the dancehalls of towns throughout Europe, and in the second half of the century returned to the countryside. During this time the mazurka also came to Slovenia and became established in all regions except Resia. It lost its elements as an urban dance and was simplified: it is usually danced in a circle turning left and right with small hopping steps.

GNI M 47.457

Recorded: Dolenji Boštanj, Lower Carniola, 1998.

Sung by: Jože Sever, Andrej Lisec, Tone Lisec, Franci Lisec, Matija Lisec, and Lojze Lisec.

After the Second World War caroling was stopped for the most part, but in places continued in secret. When Slovenia attained independence, there was a revival of caroling – especially for the Feast of the Three Kings, which had been most widespread before the Second World War. In some places caroling for the Feast of St. Florian and the New Year was revived, and caroling for the Feast of St. George in eastern Lower Carniola was exceptional in preserving this heritage almost uninterrupted. Caroling by young men, which is characteristic for this region, indicates that the custom was well preserved.

As the song, which was recorded during caroling, demonstrates, caroling for the Feast of St. George was preserved in the vicinity of Sevnica in Lower Carniola. Raising of the intonation in graduated singing is unusual. In addition to the Sevnica area, this style of singing is also known in the Bizeljsko and Tolmin regions, and was also customary for singing that accompanied the ritual prvi rej dance in the Zilja/ Gail River valley.

GNI M 47.794

Recorded: Šmartno na Pohorju, Styria, 1998.

Sung by: Ana and Romana Črnko, Gradišče na Kozjaku, Styria.

This song is an example of the farewell (slovo), a memorial song that continued to be composed, especially in Styria, for unexpected or tragic deaths as late as the beginning of the 20th century. The tragic fate of the girls from Zamušani, who never returned from their day’s labor, was enshrined in memory through song. Because it was maintained as a folk song, it changed and the details were lost. In this way memorial songs become narrative songs, or ballads. Among the narrative songs still sung today, there are many for which it is still possible to find the traces of the actual tragic events in historical documents.

The recording represents an idiosyncratic style of singing, free of outside influences. It is marked by an open, sliding (glissando) singing style and unsteady intonation.

GNI M DAT 114

Recorded: Špeter ob Nadiži/San Pietro al Natisone, Venetian Slovenia (Italy), 2000.

Sung by: Marija Pija and Pio Cenčič.

Sometimes when songs were more widely adopted among people, not only were their details lost, but their roles also changed. This is true of one of the best known songs from Venetian Slovenia, “Oh My Lord.” The song was originally sung as a farewell to a bride leaving home, but with the phenomenon of migration in the 20th century it became a symbol of emigration and leaving one’s homeland. It still carries this meaning today.

GNI M 30.799

Recorded: Črnomelj, Bela Krajina, 1969.

Played by: tambura players, Sodevci, Bela Krajina.

For many people today, the tambura player is emblematic of instrumental folk music from Bela Krajina. However, the tambura only appeared in Bela Krajina at the end of the 19th century, as in other parts of Slovenia. Almost everywhere, tambura groups were part of the cultural societies’ activities; it was only in Bela Krajina that tambura players adopted the role of instrumental accompanists to folk ensembles. They brought some round dances (the kolo) from Croatia to

Bela Krajina, and they even introduced this couple’s dance, popularly called “The Imperial Cashbox.”

GNI M 46.419

Recorded: Britof near Kranj, Upper Carniola, 1996.

Sung by: Francka Čimžar and Pavla Pičman.

Humorous songs, such as the song “From Ribnica to Kamnik,” made playful comparisons between particular places and the people that lived there. Sometimes they accurately characterized the places, and sometimes they were far from the truth, as in this song. Contrary to the song lyrics, the largest center for making straw hats was located between Ribnica and Kamnik, in Domžale, and even had an American branch office. People sang such songs to pass the time and bolster local pride. Such songs were lost not only due to changing lifestyles, but also because people moved away to different areas.

GNI M DAT 104/18

Recorded: Horjul, Inner Carniola, 1999.

Recited by: Matic Sečnik.

Children’s creativity has retained its vibrancy to the present day. Folk heritage can also be found in this creativity, as shown by this old counting rhyme.

GNI M DAT 104/75

Recorded: Horjul, Inner Carniola, 1999.

Recited by: Špela Velkavrh.

Counting rhymes are still very frequent in children’s folk songs. The adoption of rhythmic or sung texts and the creation of variations occurs very quickly in places.

GNI M DAT 104/49

Recorded: Horjul, Inner Carniola, 1999.

Recited by: Martina Mole in Ana Oblak.

The busy world of childhood is also accompanied by clapping games connected to song. Unlike in the adult world, it is not important to children whether the text makes sense. In this way children’s oral tradition adopts texts from other languages, especially English today.

GNI M 46.713

Recorded: Veliki Trn, Styria, 1996.

Sung by: Albin Kopina Sr., Marko Kopina, Martin Gorenc, Franc Lekše, Tone Janc, Jože Lekše Sr., Albin Kopina Jr., and Jože Lekše Jr.

Drinking songs represent a part of living tradition that have retained their original role into the present day.

GNI M 46.716

Recorded: Veliki Trn, Styria, 1996.

Sung by: Albin Kopina Sr., Marko Kopina, Martin Gorenc, Franc Lekše, Tone Janc, Jože Lekše Sr., Albin Kopina Jr., and Jože Lekše Jr.

GNI M 48.481

Recorded: Apače, Styria, 1999.

Played by: Karl Tement, Ivan Kirbiš, and Tona Širovnik (Trio Škorci).

This example of a folk music group rounds out the selection of modern folk music. Such groups were once very common in Slovenia, but are rare today, and the fiddle as a folk instrument has also largely disappeared, except in Resia and Prekmurje.

The rašpla in the recording is a more recent dance. It appeared in Europe in the interwar period, and especially after the Second World War spread to Slovenian territory as well and became an authentic folk dance. One reason for its popularity is its relation to older dances with leaps involving both legs, and it is still practiced at some parties today.

Marija Klobčar: The Echo of the First Recordings

The audio publication Odmev prvih zapisov (The Echo of the First Recordings) is a selection of folk song recordings preserved at the Institute of Ethnomusicology at the Scientific Research Center of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (ZRC SAZU). The selected songs and their accompanying lyrics offer a concise overview of the importance of folk songs from the time of the first recordings to the present day. As the name implies, the audio publication makes it possible to listen to the oldest transcriptions made in the Slovenian lands, taking us from the earliest sound recordings to today. The selection clearly demonstrates the advances made in sound recording, but this is not the only purpose of the audio publication. The mix of folk songs also shows how much of this heritage was still alive and resonant among the common people when research was first begun. The selection also includes songs whose content or musical form extends far back into Slovenian history. This historical memory reaches back not only to before the first sound recordings, but also long before the first written records became a part of our national consciousness.

These songs can be traced back to the time when the first printed book appeared in Slovenia. These first publications drew attention to a heritage that was known only as a memory. Half a millennium has therefore passed since the first mention of folk songs in Slovenia and since the first words were recorded about this creative facet of a simple people. In certain periods – for example, during the Counter-Reformation – attempts were made to replace folk songs with songs more suited to the moral teachings of the time, whereas in other periods folk songs were esteemed. The value of folk songs was first recognized during the Enlightenment, with its concept of the centrality of man and the importance of his creativity. The few written records from that time reveal the first echoes of the richness of this tradition.

These traces continue to the Romantic era, when an enthusiasm for originality and authenticity discovered folk songs as an exceptional expression of the national spirit, and folk songs were studied to reveal the image of a nation’s soul. In the minds of the scholars collecting these songs, this image was on par with the poetics of high literary creativity. Because the folk songs did not match the level of literary poetics, the transcribers attempted to correct them to find the “original” image. This was at a time when only the lyrics were being transcribed, and such modifications to the original transcriptions are difficult or even impossible to identify.

As a more sober perspective on the world developed, transcribers began to record a more accurate image of folk songs. This image came to maturity in the extensive collection Slovenske narodne pesmi (Slovenian Folk Songs), which under the guidance of Karel Štrekelj brought together the wealth of Slovenian folk song heritage known at that time. Publication of the collection, which for the most part contains only lyrics, began with the issue of the first volume in 1895.

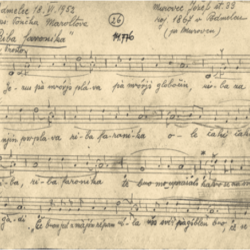

Reuniting the lyrics with the melodies of the folk songs came about only a decade later. During the extensive program undertaken by the Committee for the Collection of Slovene Folk Songs with Their Melodies, founded in 1905, various collectors gathered nearly 13,000 transcriptions of Slovenian folk songs with their melodies until the outbreak of the First World War.

Because this was a government program, the committee harmonized its efforts with the central committee in Vienna. This collection effort differed from previous ones by dedicating equal attention to the lyrics and the melodies, recognizing their mutual significance in folk songs. Because of the difficulty of transcribing the melodies, the committee tried from its very founding to purchase a phonograph – the only recording device of the day – in order to make field recordings of folk songs. They succeeded in doing this only in 1914, on the eve of the First World War. Juro Adlešič, a lawyer by profession, used the phonograph to make sound recordings of 38 folk songs in the Bela Krajina region.

Although recording folk songs with a phonograph was still a novelty at this time, researchers from abroad had made even earlier sound recordings in Slovenia. The first recordings date from 1898, two decades after Edison’s invention of the phonograph and just a few years after the phonograph became available to others. The Hungarian researcher Béla Vikár – who was the second person in the world to use a phonograph to record folk songs – reached Slovenian ethnic territory during his travels when he made his first sound recordings, in the village of Tišina in the Prekmurje region. The Russian folklore specialist Evgeniia Lineva (a.k.a. Eugenie Lineff ) – with whom the leaders of the Committee for the Collection of Slovenian Folk Songs were also in contact – recorded a number of young men’s part-songs in 1913 in Bled and the surrounding area as well as in Bela Krajina. The singing of Slovenian soldiers is also memorialized in recordings of soldiers’ songs made in Austria during the First World War.

Technological innovations after the Second World War brought about important advances in sound recording: although such development was responsible for displacing folk songs from everyday life, it also made possible increasingly accurate recording of this heritage. The Institute of Ethnomusicology – a successor to the prewar Institute of Folklore, which was unable to obtain its own recording equipment before the Second World War – received two type recorders in 1954. The first postwar recording expeditions were undertaken in January 1955 in Bela Krajina, the region where Slovenian researchers had made the first sound recordings of folk songs.

Until the mid 1990s, tape recordings were the predominant method of making field recordings, and tape recordings therefore form the foundation of the sound archives of the Institute of Ethnomusicology. The transition to the digital recording of field material in 1994 made the sound recordings cleaner and the audio material easier to access, and also made the archiving process more secure. This recording technology therefore marks the latest period of the Institute’s work, which is also reflected in the last recordings selected for the audio publication.

The span of over a century illustrated in song on the audio publication also represents continual advances in sound recording possibilities and quality, and at the same time a period of rapid change in folk culture and, consequently, folk songs. The material on the audio publication is grouped into major three time periods based on these factors.

The first group consists of the very earliest recordings made on wax cylinders and never released before. Although these recordings are the least clean from the technical point of view, the testimony they bear is exceptional. To make these recordings available, it was necessary to use techniques that would not impair their documentary value. The second and most extensive group encompasses postwar tape recordings. The variety of the folk song heritage recorded during this time most completely demonstrates the significance of this tradition. The songs captured on tape point to the most frequent occasions when the songs still performed their original roles: these include young men’s songs from when the vasovanje courtship tradition was still alive during the first years after the war, music to accompany traditional weddings, songs sung at wakes for the dead, and music corresponding to the most important holidays of the year. These are preceded by a recording of the song of Pegam and Lambergar, sung at the Institute by France Kramar, the most important collector in the program of the Committee for the Collection of Slovenian Folk Songs. The third group in this survey includes contemporary folk music. These high-quality recordings demonstrate that, despite the diminished role of folk songs, some types have been retained in their original form, while others are preserved as adaptations.

The arrangement of the songs and melodies collected on this audio publication follows a timeline, while their selection reflects the variety of folk song and instrumental music in both content and melody. The relation between the one and the other illustrates the relation between folk song and melody in actual life. The selection of melodies also takes into account their role in folk dance. The selections also include individual spoken or rhythmic texts that were unaccompanied by a melody. The songs recorded with one voice do not indicate that they were originally sung solo; in these cases, the sound recordings illustrate only the melody rather than the manner of singing. All Slovenian ethnic regions – including cross-border areas – are included in this collection, and an effort has been made to exclude folk songs that have already been popularly revived through the release of other recordings.

The release of this audio publication marks the 70th anniversary of the Institute of Ethnomusicology and the centenary of the most important program ever undertaken to collect folk songs in Slovenia, and it will help to correct some popular misconceptions about folk songs. The examples from over a century of recordings demonstrate that folk songs are a part of folk art expressed equally through lyrics and melody. These were folk songs sung by common people, including old now-forgotten narrative songs such as the song of Pegam and Lambergar and Beautiful Vida. People also sang the songs that are today preserved only as skillful yet simple rhythmic texts because only the lyrics were transcribed. They sang these to brighten their everyday lives and make holidays more festive, and they sang them to better preserve them – for themselves, as well as for their children and their grandchildren. Many of these songs are still sung today.

These songs, pressed into wax cylinders, collected on magnetic tape, and captured in digital recordings, are inscribed into the memory of the nation. This memory enriches us and binds us together – not only on festive occasions, but also in our everyday lives – and we can compare this tradition to that of other nations with pride.