White Carniola and Kostel: A Selection of Original Recordings of Traditional Music

GNI M 34.434

Recorded: Krašnji vrh, 1973

Sung by: Ivanka Cesar, Ana Vivod, Ivanka Marinac, Ivanka Režek, Ivanka Matošič, Barbara Režek, Marija Jamšek, Ivanka Matošič Jr. and Ana Golobič

“God Grant, God Grant a Good Evening” is a version of a Midsummer Night song. In addition to the usual songs or wishes, the repertoire of Midsummer Night carolers also included special songs for individual houses, professions, and even one for single people or married couples. The greeting song featured here is meant for unmarried girls or their parents. The singers naturally wanted the girls to wed the best husbands. The poetic metaphor of the sun, never changing and eternal, represents the groom. It is hoped that wedlock will be the same. The singers probably adopted the image of the moon and sun from other, mostly mythological, songs, which more frequently describe a solar or lunar groom. The transfer of motifs is a common occurrence in folk songs. In the Midsummer Night song this is even more understandable because the motifs correspond well with the content of Midsummer Night festivities and its beliefs in the sun’s power and eternity.

The short melody, with its four-note range, a sign of its archaic origin, is sung antiphonally in two groups because stopping would cause bad luck. To create the effect of wholeness, the last note of the first group and the first note of the second group coincide; the resulting note is a linking element with which the Midsummer Night carolers achieve uninterrupted singing.

GNI M 24.461

Recorded: Špeharji, 1961

Sung by: Marija Lakner

Even though this song is known in the neighboring Karlovac area, from which it spread to White Carniola, it originates from the Kvarner Gulf and Istria region. This is apparent from its melodic structure, which is typical of this area. According to the informants, the song was brought to White Carniola by a Croatian woman and was then learned by some Slovenian singers, although it did not become widespread like other Croatian songs in White Carniola. It is also relatively unknown in areas where the Croatian Kajkavian dialect is spoken.

The content of the song is categorized among Croatian versions that express the pain of a young girl when faced with the departure of her sailor sweetheart. In more distant versions, she only recognizes his boat at sea when she sees the sail that she sewed herself. In a second group of versions, which includes the version on this audio publication, the girl recognizes her lover by his shirt, which was sewn by his entire family, but the largest part was the girl’s because put her heart into it. In the version featured on this audio publication, she simply ironed it; in other versions did so directly – lyrically speaking, she dried it on her heart.

GNI M 24.508

Recorded: Predgrad, 1961

Sung by: Meta Štaudohar, Marjeta Smuk, Katica Bižal and Katica Štefanc

Today, this song is most often associated with the Prekmurje and it is attributed to this region. The White Carniola version is quite similar in terms of content, but has its own unique melody and parallel harmonies unusual to Slovenian folk part-singing. The Prekmurje and White Carniolan tradition borrowed the song from the Croatians, where the song is sung from Međimurje County to Dubrovnik. However, the Croatian versions have a substantially different melody and lyrics, the only common feature being the basic motif. It is thus assumed that the Slovenian version has a long tradition of its own. Similar melodies to that of the Prekmurje version are found in Slavonian versions of wedding and love songs, whereas the melodic versions of the White Carniolan song still somewhat resemble the melodic character of those from the Kvarner Gulf and Littoral.

GNI M 42.754

Recorded: Zemelj, 1985

Sung by: Amalija Malešič

This folk love song, which is well known throughout Slovenia, is also popular in White Carniola; the featured version is sung to the melody of “Vrtec ogradila bodem” (I Will Enclose a Garden). It is not unusual for a melody to travel from one folk song to another; this is common when the verse has the same metric and rhythmic structure (in this case, the octameter) and is thus compatible with any melody with the same verse system. It is through such a process that many lyrics began to be used in the first place and were transferred into oral communication because they had acquired a melody; however, certain songs obtained several musical versions.

GNI M 24.349

Recorded: Nova sela, 1961

Sung by: Alojzija Pantar

Similar to elsewhere in White Carniola, people in the Kostel region also sing softly, in a style known as d(i)jačenje. This denotes a type of slow, sometimes recitative, singing that they adopted from their Croatian neighbors or inherited from their Uskok ancestors that once fled the Cetina River area (Cetinska krajina) in Dalmatia and also settled in the Kostel region. The origin of the name for this singing style is not entirely certain; the name is most often associated with church deacons (džakoni) and their manner of singing (slow and monotonous melodies resembling litanies). This is not only due to the melody, but also the dialogue between the singers, either when they are calling to one another, or when they share certain parts of the song.

In the example presented here, the Slovenian singer reconstructed only an excerpt from memory to demonstrate how people once sang or how they still sing in neighboring Croatia.

GNI M 27.232

Recorded: Črnomelj, 1965 (Festival of St. George)

Played by: a group from Črnomelj

When pasturing was still practiced, the bark horn was a relatively widespread instrument, especially among shepherds that made them and used them to pass the time or for calling and signaling. In the past, White Carniolan boys would accompany St. George’s caroling by blowing bark horns.

GNI M 24.069

Recorded: Vas, 1960

Recited by: a child

GNI M 24.070

Recorded: Vas, 1960

Sung by: a child

GNI M 24.073

Recorded: Vas, 1960

Sung by: two children

All three of these songs were sung or recited by children, confirming the long-established fact that not only did children sing children’s songs or those with a children’s theme, they also liked to borrow songs from the “grownup” repertoire. The first of the three is the only children’s song, a counting rhyme for various games, whereas the second one has a love theme and must have made its way into the children’s repertoire primarily because of its rhythm, rather than its content. The third song, however, appealed to children because of its humorous and rather “naughty” theme, making it much easier to remember (especially because they teased not only adults, but also their peers). The first stanzas of the teasing song show that the piece is modern, using rhythm and various stylistic devices to mimic traditional counting rhymes and humorous songs.

GNI M 37.205

Recorded: Krašnji vrh, 1977

Sung by: Danica Ratkovič

The singer’s mother from Krašnji Vrh in White Carniola heard this song in the neighboring Croatian Žumberak Hills sometime at the beginning of the twentieth century. The singers liked its humorous theme. They “adopted” it and sang it to children as a humorous song or used it to poke fun at adult, rather indecisive, men.

GNI M 25.250

Recorded: Sinji vrh, 1962

Sung by: Katarina Žalec and Marija Madronič

White Carniolans usually sang this type of toast song at weddings in order to encourage the guests to drink.

GNI M 24.477

Recorded: Zilje, 1961

Sung by: Franc Grdun, Alojz Balkovec and Jože Čadonič

This song uses Christmas motifs connected to New Year’s well-wishing. From Christmas to Epiphany, carols were often linked to Christmas and, with a few alterations, were sung throughout the Christmas season, even for the second holy night (i.e., New Year’s Eve).

The male two-part singing in thirds with a range of four notes, together with other musical elements (e.g., a one-line stanza), shows that the example is old.

GNI M 24.356

Recorded: Nova sela, 1961

Recited by: Alojzija Pantar

This song started off as a Christmas carol, already sung at the beginning of the twentieth century on the thresholds of Slovenian houses by Croatians from the Žumberak Hills. This was done on Christmas day. White Carniolans used to say that the Vlachs (also known as Unijati ‘Uniates’) cast spells on Christmas. The theme itself has a Christmas motif, a young Christ-child, which coincided with Slovenian New Year’s caroling. Similar carols with a motif like this are not found elsewhere in Slovenia. It is therefore a typical White Carniolan carol that was (once) sung. The institute’s associates recorded it when it had already lost its melody.

GNI M 28.935b

Recorded: Zgornji Suhor, 1968

Sung by: Alojz Orlič and Anton Željko

Like elsewhere in Slovenia, boys in White Carniola would go around caroling during the Christmas season, singing and asking for gifts. The highpoints of the season were the three holy nights (Christmas, New Year, and Epiphany) and in folk belief they were all equally important. People did not consider Epiphany simply the religious holiday of Christ’s revelation. For farmers in particular, it also represented an important date when the day grew a “hair” longer, as a sign that the sun was regaining its power. The weather on Epiphany also supposedly forecast next year’s crop yield. This worry and hope encouraged year-round caroling. The Church tried to cover up these “pagan” rituals with its own holidays or imbue folk traditions with Christian themes. In the sixteenth century the Church therefore introduced or sanctioned Epiphany caroling for this holiday.

GNI M 42.793

Recorded: Kapljišče pri Podzemlju, 1985

Sung by: Marija Štefanič, Malka Kralj, Marija Brodarič, Nada Štefanič, Pepca Jaklič and Marija Kralj

In the past, weddings had an obligatory “protocol” that was adhered to during the entire ceremony: from when the bride left home to the end of the wedding, which lasted several days, when they collected gifts for the musicians, the senior female organizer (starešina), and the cooks. After the wedding ceremony, the bride received gifts from the guests. She was usually given coins inserted into an apple or the wedding cake. Naturally, the gifts were given in a fixed order: the unmarried male wedding organizer (camar) sang a song in which he first invited the bride’s parents to come forward to give gifts; these were followed by the brothers and sisters, and later all the other relatives. The melody of this wedding song was borrowed from the song “Vrtec ogradila bodem” (I Will Enclose a Garden).

GNI M 20.051

Recorded: Preloka, 1955

Played by: unknown musician

This recording is an example of a double-reed whistle, also known in White Carniola as diple or svirale. The diple could be fastened to an animal bladder, thus creating bagpipes.

GNI M 36.944

Recorded: Bojanci, 1976

Sung by: Niko Vrlinič

This song could also be classified as a dance song because White Carniolan Serbs from Marindol and Bojanci usually sang it while dancing the kolo or as an accompaniment to it. It is some sort of emotional message to a wide circle of listeners and dancers about the broken heart of a girl abandoned by her sweetheart. It was thus also performed on other occasions. Thematically, it is a love song.

GNI M 36.929

Recorded: Bojanci, 1976

Sung by: Ljuba Vrlinič, Zorka Vrlinič, Zlata Vrlinič, Ljuba Vrlinič, Bosiljka Radojčič, Simon Vrlinič, Niko Vrlinič and Simon Radojčič

Similarly to the “White Dove” song, this is an important part of the song heritage of the White Carniolan Orthodox community. This is demonstrated in the slow and melismatic singing of the repeating one-line stanza by the lead singer and the accompanying group. This song was sung during dances and on other occasions, because its emotional and commemorative motifs ensured it a long life and various functions. It is usually an attractive theme that saves a song from obscurity, even though its primary function (dance or ritual) is lost.

GNI M 24.449

Recorded: Predgrad, 1961

Sung by: Meta Štaudohar

In the mind of many Slovenians, this song is meant for children because they become familiar with it in preschool. It is not only a song, but also a game. Even at the end of the nineteenth century, it was still a dance song that White Carniolans performed in combination with a dance on Easter Monday. Today, this song is kept alive as a dance and dance song by various Slovenian folk-dance groups.

GNI M 44.189

Recorded: Dolenjci, 1987

Sung by: Anica Bahorič, Marica Bahorič and Katica Kapele

In Slovenian folk songs, this stanza often begins the legendary song about Christ the Gardener. Similarly, it is also the start of love songs, like this one. Even though other versions are used elsewhere in Slovenia, records and audio recordings show that it is most common in White Carniola. The White Carniola versions are somewhat different in terms of lyrics and motifs. In addition, the diction and metaphors of certain passages are reminiscent of Kajkavian love songs.

GNI M 28.924

Recorded: Zgornji Suhor, 1968

Sung by: Alojz Orlič

The Christian St. George probably replaced the old Slavic figure of Jarnik or Vesnik. At the end of April, when St. George’s Day begins, the sun becomes stronger and the grass begins to turn green. This is why all the rituals were connected with the sun and greenery. A golden vessel or mirror fell from the sun, which represented good luck. The well-wishers were St. George’s Day carolers that spread greetings from door to door and collected gifts. Today, St. George’s Day celebrations are mostly connected with White Carniola, where it was preserved the longest, even though it was once known throughout Slovenia, especially in Carinthia and Styria.

In White Carniola, St. George’s Day carolers sang various songs dressed in white and adorned with greenery. In Slovenian collective memory, the best-known carol starts with Prošal je, prošal pisani vuzem, / došal je došal zeleni Juraj (Colorful spring has come / Green George has arrived). This audio publication includes a less familiar version; it is a combination of different carols, starting with many happy returns for the New Year and thematically immediately jumping to the St. George’s Day carol.

GNI M 24.474

Recorded: Zilje, 1961

Played by: Franc Grdun

The dvojnice, also known as diple or svirale in White Carniola, is a type of double whistle that was used as an instrument by shepherds; however, it is best known for being a Midsummer Night caroling instrument: the musician playing the dvojnice (the piskač ‘piper’) used to accompany Midsummer Night carolers in certain White Carniolan villages. An improvised melody was introduced into the Midsummer Night carol and then used to provide unbroken accompaniment, because it was believed that interrupting the flow of music brought bad luck.

GNI M 44.198

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1987

Sung by: Stanka Veselič, Marija Petek, Anka Adlešič, Marija Vranešič, Katica Adlešič, Marija Cvitkovič and Bernardka Adlešič

Midsummer Night celebrations and the rituals and songs that went with them were once known throughout Slovenia. Today, their original function is only preserved in the White Carniolan village of Adlešiči. On the eve of the Feast of St. John the Baptist (23 June), the men would prepare the bonfire and the women would go from door to door and sing special good-luck songs to the house, its master, the housewife, the field, and the crops. They were most often given food, and later money, as thanks. If a household refused to give gifts to the women, they had extra verses in store that were used for bad luck. The singers were usually accompanied by a musician with a flute (dvojnice or diple), and even with bagpipes in the past, who also protected them.

The song featured on this recording is one of the best-known Midsummer Night carols. The Adlešiči singers sang it to two different melodies. In the old, three-note melody featured here, the singers chase each other. This means that one or more singers sing the first verse and, before they finish this verse the other group starts. This goes on in alternation through the entire song. This is not simply musical ornamentation; it also comes from the old magical belief that a song (or an incantation) could not be broken, or bad luck would ensue.

GNI M 42.773

Recorded: Podzemelj, 1985

Sung by: Ana Pezdirc iz Boršta

“Oj, oj, i meni, mamica” is a love ballad about a smitten young man. Because he was unable to lure a girl to him through great deeds (e.g., building a church), he does so by faking death. In 1895, two versions were published in Karel Štrekelj’s collection (Š, 112 and 113). One was recorded in central Slovenia, and the other in the northwestern part of the country. Later recorded versions (13 altogether) kept by the ZRC SAZU Institute of Ethnomusicology show that this ballad about an enamored young man was primarily sung in regions on the margins of Slovenian territory, from Prekmurje to Resia. In 1985, the song was also recorded in the White Carniolan village of Podzemelj and information showed that it had already been sung here in the second part of the nineteenth century. Today, the song is no longer known elsewhere in Slovenia. The motif of faked death is also present in the ballad “Mlada Zora” (Young Zora), in which two lovers fake death in order to receive the blessing for their marriage; however, in this song the young man deceives the girl. Even though these are two separate song types, the question is whether the second is merely a version of the “Mlada Zora” type that changed somewhat over time in the oral tradition and developed into an independent song with a similar motif, but a slightly different plot.

GNI M 26.042

Recorded: Stari trg ob Kolpi, 1963

Sung by: Ivanka Štrbenc

All of the White Carniolan versions of this song are of Croatian origin because the area has a number of songs about the Jews trying to steal the infant Jesus from Mary. The nineteenth-century author Janko Barle recorded that the song was brought to White Carniola by the Vlachs from the neighboring Croatian Žumberak Hills traveling through the area as carolers and collecting gifts along the way. Barle also wrote that the versions had a “very monotonous” melody. In over a century, the song has also changed linguistically. The version presented on this audio publication already shows more Slovenian elements than the versions recorded earlier. This version also shows how the original legendary song acquired the function of a carol and as such began to be used in Slovenia.

GNI M 24.329

Recorded: Nova sela, 1961

Recited by: Ana Padovac

This is one of the numerous versions of the apocryphal prayer about the suffering of Christ, known in Slovenia and throughout Europe as the “golden Paternoster.” These kinds of prayers flourished during the Baroque period. They were either printed or transmitted orally, and have been preserved to this day as personal (not Church) prayers. What these prayers have in common is their theme; however, in terms of motif, they vary a great deal because they are considerably individualized. The motif versions of the prayer released on this audio publication can be found in Lower Carniola. The prayer was usually used as a Friday prayer because in Christian tradition Friday is the day of Christ’s death. This prayer is shorter than other known versions of Christ’s suffering. Certain imagery of Christ’s blood points to the possibility that it was primarily used on the first Friday of the month, after the Church had also introduced the Nine First Fridays devotions (with indulgences).

GNI M 45.323

Recorded: Žeželj, Vinica, 1989 (bell chimers’ gathering)

Played by: bell chimers from Zilje

The names of bell-chiming melodies often denote their place of origin. Thus, this group from Zilje probably named theirs after Metlika. The melody played on three bells consists of regular repeated strikes on the large bell, whereas the second and third bells alternate their roles by filling out the melody using syncopation, known as gostenje.

GNI M 45.942

Recorded: Marindol, 1991

Sung by: Marija Bunjevac

In the past, people from White Carniola used to lament the deceased (the practice was called ladanje, bugarjenje, or divanjenje) with characteristic melismatic singing about his life or about the tragic loss of a fellow human being, relative, or acquaintance. In White Carniolan Orthodox villages (Bojanci, Marindol, and Paunoviči) this was called naricanje or tuženje. Today, this form of lamenting the deceased through song has almost disappeared; however, until recently it retained its function among White Carniolan Serbs.

The song presented here does not belong among the old lamentations, but is instead a more recent dirge that, according to the singer, came to Marindol from Bosnia and became popular. The hand-washing ritual performed if one came into contact with the deceased and described in this song is reminiscent of older layers of Balkan mourning songs (tužbalice).

GNI M 26.038

Recorded: Stari trg, 1963

Sung by: Ivanka Štrbenc and Kristina Majerle

Today, White Carniolans perceive this song as their own, which it truly is; they have adapted it to fit their emotions and language, singing it as a love song. In the past it had various functions: it was sung as a ritual (Midsummer Night) song as well as a wedding song. Consequently, many lyrical versions are still used today. Depending on the area, these can have a stronger Slovenian or Croatian linguistic image, demonstrating that these songs have been present in White Carniola for some time, but are of Croatian origin.

GNI M 20.057

Recorded: Adlešiči, 1955

Sung by: group of singers

Even though this song’s motif, lyrics, and musical versions are known practically throughout Slovenia, its “original homeland” is White Carniola. The song probably only spread from White Carniola during the First World War (except for the eastern Slovenian versions, which were already known in the nineteenth century and came from Međimurje). This song also came to White Carniola from Croatia and was altered not only linguistically, but also in terms of genre. The original heroic ballad became markedly lyrical in White Carniola, thus losing some of its South Slavic epic narrative quality, breadth, and heroic emphasis.

GNI M 24.007

Recorded: Fara, 1955

Sung by: Marija Marinč and Katica Jakšič

This is a more recent sentimental love song that was originally probably a love ballad, but its narrative core was lost because the singers kept only the part or motif they found most interesting. The theme is obscure and deals with an enamored girl that wants to be her wounded or ill sweetheart’s nurse. The end, where she dies of grief when she learns that her beloved has passed away, somewhat resembles themes found in older ballads. However, because this song does not appear in old recordings, one may assume it is a new love song that resembles love ballads due to its narrative structure and tone. In White Carniola and elsewhere in Slovenia, only versions similar to this one have been recorded. It is therefore difficult to ascertain whether the song was truly narrative once and was only later reduced to its present lyrical core through the communication process.

GNI M 28.179/b

Recorded: Ljubljana (Institute of Ethnomusicology), 1967

Sung by: Marica Skube from Adlešiči and Stanka Veselič from Vrhovci

In addition to this version, which is the most widespread in White Carniola, somewhat longer ones exist as well. All the versions have the same central motif: an unhappy youth that is rejected by a girl, either because she does not like him or he is too clumsy, or the girl has already chosen another. The versions from White Carniola have only retained the refusal motif, but not the reason for it. This further influenced the diction, which turned from its somewhat melancholy lyric nature to a more joyful one. White Carniolans usually sang this song while cultivating the vineyards.

GNI T 114B/14

Recorded: Jakšiči, 1960

Sung by: Ana Delač and Marija Marinč

White Carniolans and the people of Kostel, who left their homes for America in great numbers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, frequently experienced the severing of family and romantic ties because of separation. This song bears testimony to this. However, judging by its language and melody, the people of Kostel adopted the song from the Croatians. The melody comes from another Croatian love song (“Čula jesam, da se dragi ženi” – “I Heard That My Beloved is Getting Married”), which has an almost identical motif of an unfaithful sweetheart.

GNI M 25.254

Recorded: Sinji vrh, 1962

Sung by: Katarina Žalec and Marija Madronič

Karel Štrekelj’s folk-song collection from the beginning of the twentieth century indicates that this song was popular in most parts of Slovenia. It was most frequently recorded in Styria, from which it must have spread to other regions, mostly wine-growing country. From Lower Carniola, the song also came to White Carniola, where it is still sung. Similar to many Slovenian toasts, this one also works like a “chain.” All of the verses have the same melody and lyrics; the only thing that changes is the name of the one toasted or the name of a new drinker. The number of verses with invitations to drink thus equals the number of people drinking or guests. Naturally, all of the drinkers would like to sing as many verses as possible.

GNI M 24.469

Recorded: Stara Lipa, 1961

Sung by: Kristina Rogina, Angela Muhič, Ančica Videtič and Katica Rogina

Information indicates that this song, which the singers considered very old, was probably created in the nineteenth century and was documented in Slavonia at the time. From there it spread to White Carniola through the Kajkavian region.

GNI M 24.050

Recorded: Vas, 1960

Sung by: Katica Jakšič

This well-known Slovenian humorous song about a cross wife and happy widower is also known in White Carniola.

GNI Perudina, 22. 8. 2007, Blkr.

Recorded: Perudina, 2007

Sung by: Janko Balkovec

The White Carniolan folk musician Janez “Jazo” Štefanič was known for entertaining people and accompanying dancers on the friction drum (gudalo) and harmonica (muzike) simultaneously. Janko Balkovec, who is heard on this recording, is the third consecutive musician to play the two instruments simultaneously, thus preserving the image of Jazo. This image is so celebrated that every time Janko Balkovec goes to perform he says he is “off to play Jazo.”

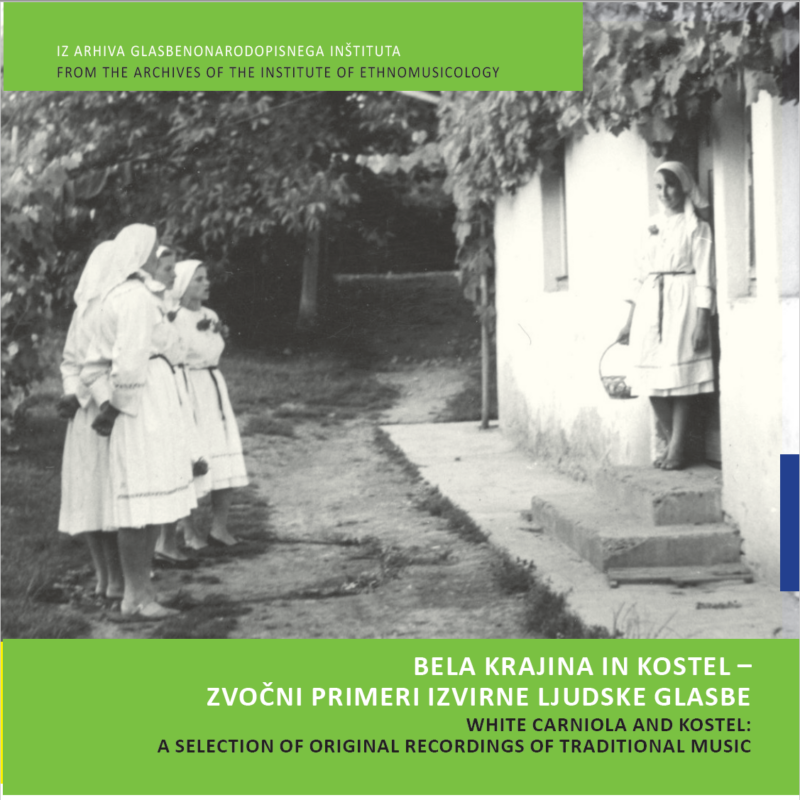

Marko Terseglav: “My White Carniola, Open the Door to the Light” (O. Župančič)

White Carniola, once called the Metlika March, lies in southwestern Slovenia and is nestled between the Kočevski Rog forest and the western part of the Gorjanci Hills. To the south, it is bordered by the Kolpa River. The name White Carniola was not mentioned until the nineteenth century as a folk concept distinguishing between the “black” (i.e., Lower) Carniolans and the “white” Carniolans. The White Carniolan national costume was white and consequently different from the attire worn by neighboring Lower Carniolans.

Due to its geographic isolation from major trade routes and its historical position on the border and exposure to Turkish attacks, the region attracted the interest of travelers and explorers. It was first accurately described by Johann Weichard Valvasor in his work “Die Ehre deß Hertzogthums Crain” (The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola), in which he also published the lyrics of a White Carniolan or Uskok folk song. The writer Janez Trdina later described the inhabitants of the lands under the Gorjanci Hills as the most nationally conscious and speaking the purest Slovenian, in addition to being traditionally hospitable. After him, intellectuals and folklorists studying the region discovered traditions that were only preserved here and could no longer be found in central Slovenia. In the minds of Slovenians, White Carniola long remained naturally and culturally the most intact region; at the same time, it was always known for its cultural uniqueness that almost bordered on the exotic. This nearly romantic excitement involved a great deal of exaggeration. However, it is true that White Carniola did somewhat stand out because of its historical fate. When Slovenians first settled this area in the thirteenth century, they encountered the neighboring Croatians and their culture. In the sixteenth century, the Uskoks brought their own linguistic and cultural diversity with them as well. They were a group of South Slavs that fled from the Turks and temporarily or permanently settled the southern regions of White Carniola, the Poljane Valley, and Kostel, which ethnologically and linguistically still belongs to White Carniola.

The White Carniolan dialect is made up of three major subdialects: the northern (including Kostel), the central, and the southern. The northern and Kostel subdialects are connected with Lower Carniolan, primarily the Ribnica subdialect, whereas the southern or Kolpa Area subdialect includes traces of Serbian and Croatian.

The region’s cultural and ethnographic characteristics are similar to its linguistic features because general Slovenian and Lower Carniolan song, music, and other elements mix with Uskok ones. This selection of songs seeks to mirror this linguistic, cultural, and singing diversity. Thus, well-known folk songs popular throughout Slovenia are presented alongside songs adopted from Croatia. These songs have been sung by the White Carniolans for so long that they have altered them and given them an almost Slovenian “idiom.” This audio publication also contains three examples of a capella music by White Carniolan Serbs from Bojanci and Marindol. The choice of songs seeks to present the various song genres and at the same time draw attention to characteristic White Carniolan songs, such as ritual songs (St. George’s Day carol and Midsummer’s Night carol) or certain ballads not known to other Slovenian regions (e.g., “Oj, oj, i meni, mamica” – “Woe is Me, Mother”).

Audio recording in White Carniola began as early as 1914, when Juro Adlešič recorded singers from Adlešiči and Preloka on a phonograph. These recordings have been released elsewhere and are thus not presented on this audio publication. The collection is based on audio recordings from the Institute of Ethnomusicology made in White Carniola from the late 1950s to the present. Despite occasional deficiencies in sound quality, these are nonetheless valuable archive recordings of great cultural and documentary value. This value mitigates unwanted background noises (e.g., speech and other sounds one is not accustomed to hearing during singing). However, on documentary recordings such “field sounds” are sometimes unavoidable.

The goal of this audio publication was to present as many White Carniolan places or at least districts as possible and thus achieve greater diversity and a more comprehensive sound image of White Carniola. Even though certain singers were more frequently featured on the recordings, the song selection sought to present not only unison singing but also two- and multi-part female and male singing. The children’s songs include a few recited ones.

Because White Carniolan instrumental folk music is featured on a different audio publication, only a few such recordings are presented here (again to achieve greater diversity).