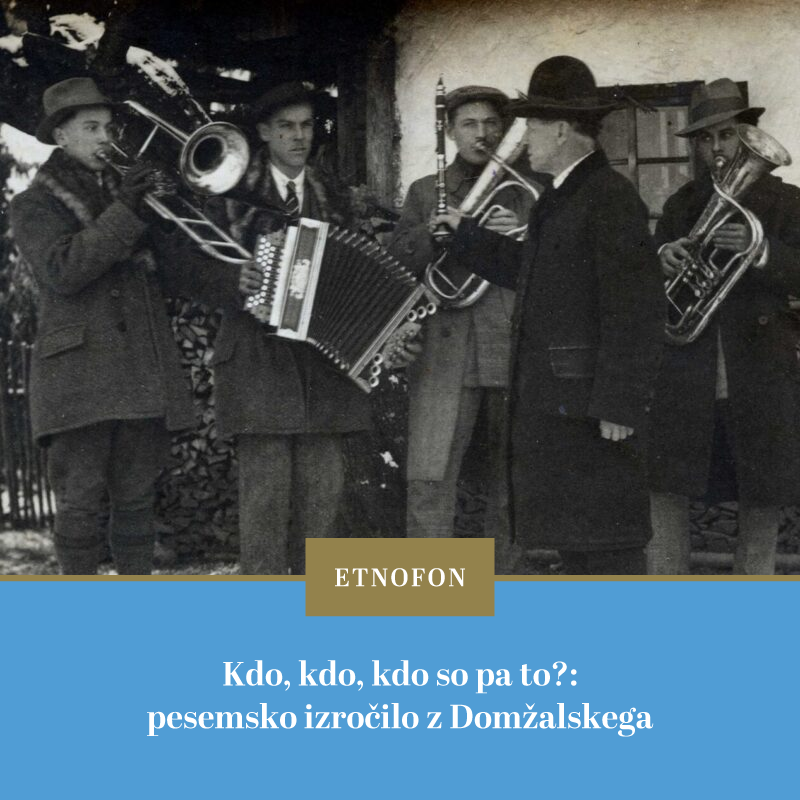

Who, Who, Who Could They Be?: Traditional Songs from the Domžale Region

GNI M 20.713

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The oral tradition concerning the merman, first attested in Slovenia in Valvasor’s story about the dance under the lime tree in Stari trg in Ljubljana (Valvasor, 1689a, XI: 685; 1689b, XV: 460–461; Merhar, Matičetov, 1970: 144–145), is intertwined in this song with the legend about the dovji mož (wild man). This story was widespread in the Kamnik region but was tied mainly to the area of the Bistrica valley and the mountains themselves. In the song, he appears under the local name for a more widely known mythological character, the merman.

GNI M 34.115

Recorded: Ihan, 13. 5. 1972

Sung by: I. Pirc (*1904)

The narrative song about a wedding and the curse cast by the deceived girl Lenčica upon her former lover refers to medieval social structures and the upper social class. In one of the variants of this song (Kumer, 1962: 193), this can be discerned from the warning that the wedding party don’t scream or whistle when they ride through Mengeš. In the Ihan variant, this detail is not preserved, but the warning is emphasized. This was supposed to prevent the wedding party from being noticed by the scorned girl who had a child with the groom but did not belong to the same social class. The wedding party forgot the warning and enabled the girl to cast the curse.

GNI M 34.064

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The mythical narrative song Fantič je hodu prou deleč v vas, typologically classified as The dead man’s bone punishes the reckless, is known in Slovenia in the wider Kamnik-Domžale area, and was sung pǝr mrlič, i.e., at the wake. The content is familiar to the wider European area and the French, the Spanish and the Flemish also know it in song form (Kumer, Matičetov, 1970: 208–209).

GNI M 29.731

Recorded: Krtina, 16. 1. 1969

Sung by: K. Sušnik (*1896)

The song is mythical in terms of its content, but has been preserved because it is sung during wakes for the dead, so it is a type of ritual song. The content refers to the legend of Mary and the sunken villages. The original connection with the Rhine River (Kumer 1981a: 323), which arose from the pilgrimages of Slovenes to Aachen and Cologne, was gradually replaced by the Danube after the abolition of these pilgrimages in 1775.

GNI M 20.720

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The song about a boy’s encounter with Mary is one of the mythical narrative songs and has a longer tradition than can be discerned from the lyrics of this version: the “young boy” in the song is namely a character that through time replaced St. Bernard. The worship of this saint was spread by the Cistercians, and his resonance among Slovenians is also evident from the fact that the Cistercian monasteries in Stična and Vetrinje were founded during his lifetime (Kumer, 1981c: 473). The underlying message of the song was conversion, illustrated by the fact that the boy’s whistling, singing and playing were not an expression of frivolity, but of spiritual experience.

GNI M 34.063

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The song about Saint Alexius summarizes the story of the medieval legend about Alexius, the son of a Roman patrician (Kumer, 1981b: 418–419). It tells the story of his life, in which he renounced wealth and married life, and his even more famous death, which was to reveal his sanctity to the people. The selected variant no longer has a clear conclusion.

GNI M 30.610

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: K. Škerjanec (*1903) in T. Podboršek (*1925)

The narrative song about the poor pilgrim Mary who asks the boatman to take her across the water for free is widespread in Slovenia. It is not clear from the song which environment it refers to, but it indirectly preserves the memory of the special rights of Slovenian pilgrims and their violation. As a saint’s legend, the song was sung on pilgrimages and at wakes for the dead, as well as at gatherings during seated work.

GNI M 30.606

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: K. Škerjanec (*1903) in K. Podboršek (*1925)

The song about St. Margaret of Antioch with its depiction of the life of this saint aligned with the version in Legenda aurea, very clearly points to the creativity of an educated author, most likely an organist or schoolmaster. The most important keepers of such tradition were church singers.

GNI M 20.705

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The song about the Prague saint John Nepomucene was one of the songs that, especially in the Baroque era, provided religious catechesis and its spread was linked to traveling singers. At the time of its greatest popularity, it was considered a favourite (Klobčar, 2020: 85–86, 256), and the popularity of this saint was also expressed by chapel depictions mainly associated with crossings over water. The word korar as a term for a church canon had already been lost in some places, so people began to replace it with the term kolar, which completely changed the meaning. In other versions of this song, other appear instead of the Vltava, especially the Danube and the Morava.

GNI M 34.107

Recorded: Zaboršt, 6. 2. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The opening verse and the narrative lyrics of the song indicate that it served as a tool for religious and moral education. It tells the story of the pilgrimage site Tinska gora and of an unbelieving man who repented for his sins and was converted.

GNI M 20.703

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The narrative song about St. Lucia is mythological in content but is considered a pilgrim song because of its function. Several churches are dedicated to this saint in Slovenia, including one in Skaručna, where people with sight problems used to make pilgrimages (Kumer, 1992a: 303). The song describes the life of the saint, and list as proof of her good works the healing of a servant from the nearby area, from the Moravče parish. In the Baroque period, some pilgrimage centres had special travelling singers perform songs. This provided them with extra income and offered religious catechesis to pilgrims (Klobčar, 2020: 79–90).

GNI M 29.720

Recorded: Hudo, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Pirc (*1899), A. Gaberšek (*1905), F. Rojc (*1890), T. Šarc (*1904), J. Šarc (*1900), J. Hribar (*1914) in J. Frontini (*1906)

Songs with the motif of a bride committing infanticide were widespread almost everywhere in Slovenia, and those with the motif of an illegitimate mother who abandons or kills her child is known elsewhere in Europe (Golež Kaučič, 2007a: 712–713). The story about the bride who on her wedding day is revealed to have murdered her illegitimate child or children was widespread in the Kamnik-Domžale area and was sung mostly at funerals due to its tragic nature and moral message. In some places, such as in the Mengeš area, the song was also sung on pastures because of the appearance of a shepherd in it.

GNI M 20.704

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The ballad about the child murdering Urška refers to a real event: an entry in the account book of the city court in Ljubljana proves that a woman named Urša Mandlovka was executed for infanticide on October 22, 1766 (Kumer, 1990: 407). The song about this execution exists in many variants (Golež Kaučič, 2007b: 714–771). The version widespread in the Kamnik-Domžale area expresses great sympathy for the convicted woman and for the hardship that led her to infanticide.

GNI M 30.610

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: K. Škerjanec (*1903) in T. Podboršek (*1925)

The selected version of the song Stoji, stoji Ljubljanca (There stands the city of Ljubljana) is of a humorous as to the chorus “enà baba pa rimǝlne lom” but is otherwise a narrative song with a more serious background. Some have observed a connection with German tradition (Kumer, 1998b: 541) and the version of this song recorded in Loka pri Mengšu (GNI M 34.098) indicates that the song originates from the story of the fatal dance under the lime tree. According to this tradition, the girl dies in an endless dance with an unknown knight whom she provoked to this act with her arrogance.

GNI M 34.065

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The song about a disloyal student (a priest-to-be preparing for New Mass), which is spread throughout Slovenia in many versions, must have been written as early as the 18th century (Kumer, 1998c: 606). In the version recorded in Zaboršt, its connection with reality is expressed by the mention of the church in Šǝnklavž. The unrequited love between a theology student and a girl originated from the fact that many entries into the priestly profession were involuntary and gave rise to a lot of stories among people. In the Domžale area, the song was known as “the student song”, and the connection with the word kor was lost, so the song mentions kólars (wheelwrights) instead of kórars (choir members). The pronunciation of the ‘l’ sound instead of the ‘u’ is preserved in the song as well.

GNI M 34.067

Recorded: Ihan, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Rahne (*1909)

This family narrative song is an eloquent example of the organists’ creativity. It was composed by Matevž Kračman, a schoolmaster and organist in Šmarje, and lamented the death of his children. He spread it far and wide himself during his travels around the wider area (Klobčar, 2020: 244) and in the Domžale area its spread was accelerated by his straw-plaiting contacts too.

GNI M 34.068

Recorded: Ihan, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: J. Velepec (*1932)

The song about a murder in the village refers to a real event from 1892 (Kumer, 1998a: 319). The Ihan version preserves the real name of the victim, Tonček, and the word “štajngarski” indicates that the incident took place in the surrounding area, in the hills around Velika and Mala Štanga. The song was created as a description of the event, as a piece of news, but over time it morphed and became established as a love song.

GNI M 20.719

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

The song about a widower at his wife’s grave belongs to more recent heritage. It was known from Venetia to Porabje (Terseglav, 2007: 127–217) and was one of the most widespread narrative songs in the 20th century. Its popularity was aided by its poignant story and the songs with its lyrics was also appropriate for any poor people begging for alms.

GNI M 29.701

Recorded: Hudo, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Pirc (*1899), A. Gaberšek (*1905) in F. Rojc (*1890)

This song is an extremely interesting example of a New Year’s carol. In terms of content, it is not related to saying goodbye to the old and the beginning of the new year, but to the feast of the circumcision of Jesus, which is celebrated on the eighth day after Christmas. The Štuček family, carollers from Goričica pri Ihanu (also called Tabrskǝ because of Tabor in Goričica, and in some places even Ihanski koledniki, translating as the carolers from Ihan), used this song from St Stephen’s Day to Candlemas to wish people a happy new year in the wider region of Upper Carniola (going from Ljubljana to Moravška dolina and as far as Celje and Kranj). They carolled at wealthier houses or at the houses of more pious people. They performed some music in front of the house, sang, and then played music within the house again. The father and three sons, who played the accordion, the trombone, the clarinet and the bass respectively, were on occasion joined by a fifth musician.

Only they ever performed this song and its transmission to the next generations was ensured by the mothers of the family. It was never sung in church and its folk character is emphasized by the motif of the bishop who is to perform the circumcision ceremony “in the Jewish manner”. A special feature of this song is that it was sung in two variants, beginning wither with “Soon they will be over, oh, those eight days” or “They’ve already passed, oh, those eight days”, depending on whether they were carolling on the day before or after the new year. With this, the song enabled the combination of Christmas, New Year’s and Epiphany carolling.

The carollers from Goričica pri Ihanu used to carol with this song in the first years after the Second World War. This marked the end of the long tradition of Ihan carolling, which (before the Štuček family) also included the “wooden music” and the instrument oprekelj.

The photo of the carol group from Goričica pri Ihanu is featured on the cover of this audio publication.

GNI M 20.590

Recorded: Goričica pri Ihanu, 28. 12. 1956

Sung by: A. Kokalj (*1890)

The song reminds us of the tradition of Christmas carols, drama performances that were performed in churches before midnight in the Baroque era. These plays were banned by the decree of Maria Theresa in 1751 (Kuret, 1986: 188) but the transformed shepherd’s games were sometimes preserved as church pastorals (cit. work: 189). Dob, for example, was famous for this type of pastoral. At the beginning of the 20th century, the memory of how children used whistles to imitate cuckoos during these games (GNI O 9589) was still alive, and people would use the song Nikar ne dremajte during midnight mass in Beričevo.

GNI M 20.723

Recorded: Topole pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: J. Vahtar (*1883)

The wedding song Jeden pa po vasi hodi depicts the announcement of a wedding. It was sung by the guests at the wedding when the bride was taking leave at home before they all left for the church.

GNI M 29.727

Recorded: Krtina, 16. 1. 1969

Sung by: K. Sušnik (*1886)

The ritual song Bratec iz Jeblance or Ljubljance is a rising song, a haggadah, and had a special meaning due to its special structure and religious content. It was mostly sung at weddings, so it was known as vohcetna, though in some places it also fit in at funerals. The selected variant has the last stanzas slightly shortened.

GNI M 43.887

Recorded: Spodnje Jarše, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by S. Kralj (*1926), P. Juhart (*1910), F. Urbanija (*1927) in J. Juhart – harmonika (*1937)

Slovenes did not mark births or birthdays with songs, which is why they celebrated name days all the more solemnly. The offering was a special ritual intended to celebrate the name day on the eve of the holiday itself. Villagers or local people made offerings to person celebrating and created noise with cow bells and kitchen utensils (lids or cutlery in a glass). The commotion (which was interrupted twice) was originally used to ward off evil forces that could harm a person on their holiday, but over time, the sound retained only a social meaning. Due to a rise in living standards, the latter became much stronger after the Second World War, as it was easier for the name day celebrant to entertain guests. During this time, the offering was often accompanied by a musician with an accordion and the participants joined his musing with the previously established method of making noise.

GNI M 28.281/2

Recorded: Rača, 14. 4. 1967

Sung by: P. Cerar (*1919) in J. Kokalj (*1928)

Death was an important milestone that included the participation of the entire community associated with the deceased and incorporated funeral, pious and narrative songs during wakes. A very important role was given to the songs in which the deceased took leave of their loved ones. In the funeral song Mamca mrtva leži, the singers express the farewell of the deceased and her family members – in this case the husband, daughters, sons – and the neighbours. The custom of holding wakes for the dead, vahtanje, was still very much alive in the countryside at the time this song was recorded.

GNI M 29.707

Recorded: Hudo, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Pirc (*1899), A. Gaberšek (*1905), F. Rojc (*1890), T. Šarc (*1904), J. Šarc (*1900), J. Hribar (*1914) in J. Frontini (*1906)

The funeral song Nocojšnjo noč sem še pri vas was known in the wider Kamnik-Domžale area. They sang it at wakes (vahtanje) and used it to take leave of their family, and in some cases also their neighbours, on behalf of the deceased.

GNI M 34.093

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 5. 2. 1972

Sung by: A. Hude (*1882)

In addition to dirges and narrative songs, the tradition of wakes for the dead also preserved songs about death and the passing of time. These songs expressed the awareness of an equality from which wealth does not save: the belief that after death, the rich lie right next to the petler, the beggar, helped people to overcome everyday hardships. The baroque symbolism expressed in the song indicates that the folk tradition arose from religious hymns.

GNI M 30.610

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: K. Škerjanec (*1903) in T. Podboršek (*1925)

The song is an interesting example of a funeral song: its villotta form would make you expect a light love song, but its lyrics contradict this entirely. It only makes sense if applying the deep religious belief that death is a transition to a better life.

GNI M 28.238

Recorded: Prevalje pri Dobu, 31. 3. 1967

Sung by: A. Makovec (*1880) in M. Prašnikar (*1899)

The song is one of the few dirges that (albeit in a slightly different version) are also preserved in choir singing. The selected variant has the characteristics of a folk song and contains an otherwise unknown continuation indicating the wait for the angel’s trumpet, the expectation of the judgment day.

GNI M 30.583

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Šraj (*1898), T. Šraj (*1907), P. Mikel (*1903), A. Perne (*1917), K. Škerjanec (*1903), T. Podboršek (*1925), I. Cerar (*1909) in T. Jerek (*1902)

The dirge Oj, mamca vi, vi depicts the farewell of the deceased from her family and is one of the few funeral songs that does not have a spiritual message.

GNI M 20.720

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Recited by: M. Jankovič (*1878)

Zlati očenaš is one of the many apocryphal prayers that were originally transmitted orally by beggars as they were used to ask for gifts and alms. These prayers held special meaning for people and were primarily used by women, often as something especially valuable. The ending of the song states which souls have been saved from purgatory via this prayer.

GNI M 28.239

Recorded: Prevalje pri Dobu, 31. 3. 1967

Recited by: A. Makovec (*1880)

As defence against evil times, O, sivnǝ oblak belongs to a part of the poetic tradition that was never sung. People used it to protect their homes, fields and vineyards. The song’s magic-related origins have been obscured by the Christianised content.

GNI M 34.111

Recorded: Zaboršt, 6. 2. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The song Pojte, pojte, drobne ptičke expresses a religious person’s view of life expressed through simple nature-themed symbolism. In the selected version, the rhymes don’t quite match, but the singer recalled that such songs were sung on pilgrimages and when mourning.

GNI M 29.719

Recorded: Hudo, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Frontini (*1906)

This moralistic religious song enumerates the weaknesses of individual classes – children, girls, wives, boys and husbands. It was sung during wakes so that people could reflect on their own weaknesses which could provoke God’s wrath and the day of judgment. The song includes the easily recognisable baroque method of teaching by example and is concerned with the fact that the interests of people of a certain age are understood as a weakness. Children are not excluded as their making of toys is also mentioned. A photograph from the recording of this singer is showcased as the last photo in this publication.

GNI M 28.274

Recorded: Krtina, 14. 4. 1967

Sung by: T. Capuder (*1914) in M. Stare (*1910)

The moralistic educational song Nekaj čem zapeti draws attention to human mistakes and examples of disastrous vices, first among which is drinking, and encourages people to lead a more responsible life. These types of songs were mainly sung during straw plaiting.

GNI M 30.586

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: T. Jerek (*1902)

The educational and moralistic song Nesrečna hiša je tells the story of a drunkard who destroys his family’s happiness with his vice. This misfortune is depicted through messages sent to the drunken father by his family.

GNI M 34.102

Recorded: Zaboršt, 6. 2. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The song originates from the time of mercenary armies as can be discerned from the mention that the soldiers training in the square in Graz have curly, matted hair. Hair curling was prohibited for soldiers in 1776 (Kumer, 1992b: 13). At the time of the composition of this song, soldiers could also be accompanied by their wives, which is confirmed by the dialogue in the song. Military songs – just like narrative songs – were usually sung the longest by women. The pronunciation of the ‘l’ sound instead of the ‘u’ is preserved in the song as well.

GNI M 30.605

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: C. Jerman (*1898)

The military song Kranjski tihen so tko dejali refers to the time of Napoleon’s armies and the recruitment of boys for the war with the French. It mentions the boys’ taking leave of girls, but at the same time the necessity to defeat the opponent and having faith in Mary’s help. The song expresses the aversion to the French as infidels which was established among people as a result of the French Revolution.

GNI M 28.228/B

Recorded: Prevalje pri Dobu, 31. 3. 1967

Sung by: A. Makovec (*1880)

The version of the military song Fantje se zbirajo sung by a singer from Prevalje near Dob is an imaginary report from the front. The report is meant for the lover of a soldier who ends up shot.

GNI M 43.883

Recorded: Spodnje Jarše, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: F. Urbanija (*1927)

The song Krajnski fantje mi smo, mi strongly expresses ethnic and regional identity, but also has a strong national identity component: the regional label Carniolan was also used to denote being Slovene. The song cheered the Slovenian soldiers on the front during the First World War and also was widespread among the Slovenian fighters for the northern border.

GNI M 28.245

Recorded: Dob, 31. 3. 1967

Sung by: A. Cotman (*1887), P. Vojska (*1893), A. Keržan (*1891), A. Nemec (*1895) in F. Prener (*1908)

The song evokes the memory of lads’ singing still very much alive in some places (like Dob) before the Second World War: the lads gathered under the village lime tree, sang there, and after singing went into the village to sing under the windows of girls. They went courting on Thursdays and Saturdays and sometimes went as far as Ihan. The lads’ community was thus preserved alongside modern forms of socialising brought about by different societies and enabled the preservation of certain songs and social norms.

GNI M 28.246

Recorded: Dob, 31. 3. 1967

Sung by: A. Cotman (*1887), P. Vojska (*1893), A. Keržan (*1891), A. Nemec (*1895) in F. Prener (*1908)

Love songs such as Ko bi jaz vedela were usually sung by lads during courting, but also among girls or in mixed companies. The joint singing of boys and girls usually followed joint work; the most relaxed gathering of the young was the grinding of millet. When the recorded people sang these love songs again, they were often reminded of the traditions that were an integral part of this work.

GNI M 34.121

Recorded: Ihan, 13. 5. 1972

Sung by: F. Cerar (*1929)

Love quatrains with humorous undertones were an important part of socialising at happy occasions, especially at weddings, and were often learned from the elders by children.

GNI M 30.606

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: C. Jerman (*1898)

The set of quatrains, sung either together, independently, or in connection with the dance štajeriš, deals with the topic of love and clearly depicts the transgression of moral norms. These songs were called kvantarske and were never sung in front of children.

GNI M 34.110

Recorded: Zaboršt, 6. 2. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

A humorous love quatrain about Ljubljana coach drivers was known as ta okrogla (the round one) – a light-hearted song that could ignore strict moral principles.

GNI M 28.284

Recorded: Rača, 14. 4. 1967

Sung by: J. Kokalj (*1928) in F. Orehek (*1916)

The very interesting song Ta zmešana, in which humorous elements are interwoven with various love songs using skilful rhymes, shows that at the time this song was recorded, singing together was still an integral part of social gatherings.

GNI M 20.739

Recorded: Topole pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Dornik (*1892)

This humorous love song evokes the memory of the former transport rout along the old Viennese road that led from Vienna to Trieste (the name Dunajska cesta in Ljubljana and Črnuče still exists today), and on which roadside inns offered a lot of entertainment. This song is permeated with veiled eroticism. It was preserved in many different versions as part of the songs associated with high school graduates, who used such songs to emphasize the transition to adulthood.

GNI M 29.718

Recorded: Hudo, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Frontini (*1906)

The mocking song about the townspeople of Kamnik was known in the Kamnik and wider area in several versions. Its beginnings most likely date back to the 18th century, a time when Kamnik was still proud of its former glory, but its economic and social power was greatly weakened. The lyrics of the individual stanzas refer to the decline of the city’s economic power, and the added chorus expresses the conflict between the lads from the countryside having fun in the city taverns after the draft and the city policemen. They originate from German words linked to the assessment of recruits and the meetings of unwanted guests with city representatives: the phrase kunti noh comes from the German greeting “gute Nacht”, and the concepts sembǝr, šloh are transformed German expressions “sauber, schlecht” which the recruitment committee used to separate the boys into good and bad, i.e., useless for the army. The word toužǝnt also refers to the assessment of boys – it is a transformed German designation for a confirmed conscript (“taublich”). The word štajǝriš refers to the dance with which the song was originally associated, making the making fun of townspeople even more obvious, and the repetition of the word mǝrš indicates a forced departure. (Klobčar, 2016: 17–19, 41–56, 72, 87–90) The version selected is from Palovče where the singer Frontini (in the last photo) moved to Hudo from.

1. U Kamǝlc na placu

pa purgǝc stoji,

s te velkmu trebuham,

k en mernǝk drži.

Kunti noh, sembǝr, šloh,

mulsigeri štajǝriš,

piš me toužǝnt mangelou,

mǝrš, mǝrš, mǝrš.

2. U Kamǝlc pa imajo

že staro mejo,

nobeden sovražnik

ne pride čez njo.

Kunti noh, sembǝr, šloh …

3. U Kamǝlc pa imajo

štacune nové,

notri prodajajo

stare metlé.

Kunti noh, sembǝr, šloh …

4. U Kamǝlc pa imajo

jen strgǝn svenak,

notri zapirajo

berače večkrat.

Kunti noh, sembǝr, šloh …

5. Kamǝlške dekleta

so lahko brhké,

sonce posije,

pa v senco lete.

Kunti noh, sembǝr, šloh …

GNI M 20.727

Recorded: Topole pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: M. Dornik (*1892)

The humorous song Vsi birtje so kunštni is a mocking song that pokes fun at the cunning and craftiness of innkeepers. The dialect in the song indicates that the song primarily held meaning for the local population.

GNI M 20.730

Recorded: Topole pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: J. Vahtar (*1883) in M. Dornik (*1892)

Humorous teasing, which was a fundamental feature of mocking songs, is shown in the song Who, who, who could they be? Which refers to the folk symbols of identification of the people from Mengeš, Topole, Loka, Trzin and Dob. The song was widespread in central Slovenia and the variants differed from each other depending on which village they made fun of and which expressions the inhabitants used to tease each other.

GNI M 28.285

Recorded: Rača, 14. 4. 1967

Sung by: F. Orehek (*1916)

The is a newer version of a humorous or mocking song known for its versions mentioning girls from other towns. The fact that the girls from Domžale are addressed in this song indicates the rise of the social status of Domžale and its inhabitants, brought about by the straw plaiting industry. In the eyes of the surrounding villages, Domžale, which became a market in 1925, was more important than the rest, a fact showcased in this song as well. The singers remember that it was sung by “some partisan girl” during the war.

GNI M 30.595

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: V. Jerman (*1912)

The lyrics of the slightly more modern humorous narrative song refer to hunting, which appears in folklore mainly as mocking the hunters, as hunting was the domain of the rich. The song had thirty-seven stanzas, and the local characteristics expressed in it have lost their meaning with as time passed and they travelled out of the bounds in which the lyrics were originally composed.

GNI M 43.902

Recorded: Žiče, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: V. Poljanšek (*1926), S. Kočar (*1928), N. Potočnik (*1930) in F. Šarc (*1927)

The patriotic song Sem fantič z zelenega Štajerja emphasizes regional identity, but also the uprightness and good-naturedness of the people of Styria.

GNI M 30.5

Recorded: Radomlje, 21. 11. 1968

Sung by: J. Šraj (*1898), T. Šraj (*1907), P. Mikel (*1903), A. Perne (*1917), K. Škerjanec (*1903), T. Podboršek (*1925), I. Cerar (*1909) in T. Jerek (*1902)

The song authored by Josip Stritar and Benjamin Ipavec very documents in detail the passing of the author’s musical creativity (intended to promote national identity) through choir singing and into folk tradition. Its creation is also interesting: it was composed for the concert celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Slavic Singing Society, which took place on May 3, 1887, in the great hall of the Music Society in Vienna (Jubiläums-Konzert … 1887). It was written by Josip Stritar under the title Slovanska pesem (Slavic song), while Benjamin Ipavec prepared the sheet music as a tribute to the same society (Slovenski narod, 1887: 1). The first and last stanza have been preserved as part of folk heritage.

GNI M 34.056

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

SUng by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The lullaby Ana, tutu, zapančki lepo includes St Mary soothing the child. Symbols of heavenly happiness, such as the motif of a golden cradle with a silver hinge) appear in it just like in some apocryphal children’s prayers.

GNI M 34.057

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The lullaby Ana, tutaja makes an example of how to raise children, containing the couplet “if you don’t be quiet, you’ll be spanked”. Lullabies were primarily sung by grandmothers (rather than mothers), who had more time to look after children.

GNI M 20.717

Recorded: Loka pri Mengšu, 12. 12. 1956

Sung by: S. (?) (*1950)

In satirical songs such as Pǝru čǝru jajca žǝru, the humorous effect was created via the absurdity of what was said, so the lyrics could be composed at well in such a way that rhyme took precedence.

GNI 43.877

Recorded: Spodnje Jarše, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: K. Juhart (*1971)

Nursery rhymes are short, often humorous children’s songs that mainly accompanied playing hide-and-seek. The child on whom the last syllable of the rhyme fell had to count and then find the other players.

GNI M 43.908/1

Recorded: Žiče, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: N. N.

Nursery rhymes are short, often humorous children’s songs that mainly accompanied playing hide-and-seek. The child on whom the last syllable of the rhyme fell had to count and then find the other players.

GNI M 43.908/2

Recorded: Žiče, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: N. N.

Nursery rhymes are short, often humorous children’s songs that mainly accompanied playing hide-and-seek. The child on whom the last syllable of the rhyme fell had to count and then find the other players.

GNI M 43.908/3

Recorded: Žiče, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: N. N.

Nursery rhymes are short, often humorous children’s songs that mainly accompanied playing hide-and-seek. The child on whom the last syllable of the rhyme fell had to count and then find the other players.

GNI 43.878

Recorded: Spodnje Jarše, 13. 3. 1987

Sung by: K. Juhart (*1971)

Nursery rhymes are short, often humorous children’s songs that mainly accompanied playing hide-and-seek. The child on whom the last syllable of the rhyme fell had to count and then find the other players.

GNI M 34.066

Recorded: Zaboršt, 26. 1. 1972

Sung by: M. Gothe (*1885)

The song is classified as a drinking song and was often sung when a lot of people gathered to drink. The continuation of the opening verse (the idea that the drinker will no longer drink wine after death) somewhat mischievously justifies drinking, even if beyond reason.

GNI M 43.911–43.921

Recorded: Žiče, 13. 3. 1956

Sung by: M. Šarc *1929), H. Rode (*1930), C. Klopčič (*1927), V. Poljanšek (*1926), S. Kočar (*1928), N. Potočnik (*1930) in F. Šarc (*1927)

Songs were a common feature at drinking outings, and wedding parties in particular offered a special opportunity to sing while drinking. Such events entailed the singing of songs about wine and various toasts. These had a distinctly social character; they included everyone present and were sung to each individual until they emptied their glass. At the same time, their enjoyment was emphasized by performing movements and gestures associated with drinking.

The publication is part of the project Dostopni slovarji, dostopni posnetki, dostopna slovenščina, funded by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia.

Marija Klobčar: May This Company Live Long. Songs from the Straw Plaiting Hinterland

The songs and melodies in this online publication are a sound echo of gatherings that used to be a large part of the lives of people in the economically developed area of the Bistrica plain, the area between Trzin, Mengeš, Dob and Ihan, where the Mengeš market historically played an important role.

Due to the industrial production of straw hats, the middle of the 19th century saw this area gain an increasingly strong centre in what is today the town of Domžale. This centre consisted of four former villages: Stob, Študa, Zgornje Domžale (Upper Domžale) and Spodnje Domžale (Lower Domžale) and was easily recognisable by the Goričica hill (Bernik, 1925). The same straw plaiting industry, based on the tradition of the craftsmen of Ihan, was what linked this centre to its hinterland: the entire surrounding region wove straw into plaits that were then used to make hats, which offered exceptional opportunities for socialising and singing. The tradition of these sociable events involving singing, and near Ihan often also folk music (Klobčar, 2020: 20, 117–119, 203, 291), was preserved even after the post-First World War decline of straw plaiting triggered by the workings of the new state and changes in clothing habits.

The weaving of straw plaits in this area had its origins in the exceptional industriousness of the population. Singing was always something to accompany restful work and the events following certain completed tasks, but this connection between work and singing was greatly strengthened by the straw plaiting industry. On the one hand, it influenced the preservation of the old singing tradition, and on the other, it assisted the creation of a new stream of income in a poorer environment, where people could not make a living by cultivating land alone. Plaiting gave rise to singing, while the mobility of the population (associated with the marketing of this activity and partly also with the transit flowing through this area) brought with it new songs. These were mainly sung news, songs with a story, which were preserved among the people as narrative songs.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the popularity of the singing tradition associated with the weaving of straw plaits also garnered interest in it. In the Ihan area, Anton Breznik recorded songs at the suggestion of Karel Štrekelj (Archive of GNI ZRC SAZU, ŠZ 14, Anton Breznik, I–V), while in Domžale, Matija Rode was joined by France Kramar in recording songs from Trzin, Mengeš, Ihan, Goričica pri Ihanu, Krtina and Domžale as part of the campaign of the Committee for Collecting Slovenian National Songs (Kumer, 1999: 99–110; Klobčar, 2004: 119–132). These songs were kept in the written records of the Institute of Ethnomusicology, and some were preserved until such time as the institute’s acquisition of tape recorders. These recordings, however, no longer captured the contrast between the locals and the Tyrolean factory workers preserved in the song Domžalski Tirolci (and recorded by Matija Rode from Domžale) (Archive of GNI ZRC SAZU, ŠZ 128, III/65; cf. Kumer, 1999: 109).

Due to high traffic through this area (the result also of the former transportation routes along Dunajska cesta, the road between Vienna and Trieste, freight transport between Dragomelj and Mengeš (Bernik, 1925: 20–29), and – after 1891 – the railway between Kamnik and Ljubljana) the singing tradition cannot be clearly delineated and was influenced by many different traditions, intertwining also due to family ties or working abroad. Only a few mocking songs carry the distinct local sound registered in the song Pesem o Goriški Mariji (Mary and the sunken villages) (Brojan, 2016: 15–16) and recognized outside the are due to the singing successes of individuals in lands as distant as America and recorded gramophone records (cit. work: 204–212). These connections also arose from social gatherings during farm work. Before the Second World War, the large farms of the Bistrica plain were reliant on the help of the community during bigger and more time-consuming tasks, which offered the young important opportunities for socializing, entertainment and singing.

The recording sessions of the Institute of Ethnomusicology included singers and musicians who, as young people, used to plait straw (especially women), help with the harvest and threshing, grind millet, prop up brooms, carry girls onto the straw bales, and exploit opportunities to sing and laugh at these gatherings. That is probably why the Institute’s microphones often recorded love songs that reminded the singers of these gatherings, as well as humorous tunes. The love songs reflect the tradition of vasovanje, village courting rituals: some singers sang in the village as boys, and men from Dob still vividly remembered Thursdays and Saturdays, when after singing together under the village lime tree they went to court girls as far away as Ihan.

The recordings of the Institute in the region presented in this collection began in 1956 for the purpose of publication in Marija Jagodic’s monograph Narodopisna podoba Mengša in okolice (The ethnography of Mengeš and its surrounding areas) (Vodušek, Kumer, 1958: 185–202; [Kumer] 1993: 121–122). They were most frequent at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, and most presented songs were collected during this time. The recordings were often made at the suggestion of the local chronicler Stane Stražar, who included the contributions of Zmaga Kumer into the monographs about Domžale (Stražar, 1993; [Kumer] 1993: 121–133) and Mengeš with Trzin (Stražar, 1999; Kumer, 1999: 99–110).

The connection with the locals eased the way to collecting some older songs called žavostne, or the sad ones. The songs Ko se Anzel ženit gre (When Anzel goes to wed; which talks about a curse and reflects the structure of medieval society) and Jerca je šla po vodo (Jerca went to het water; keeping alive the memory of the merman) are both connected to Mengeš. There is an interesting mythological tradition associated with the area between Dob and Krtina (which keeps alive the memory of distant pilgrimage routes with songs such as Marija gre za Donavo or Mary goes to the Danube) and with the area around the Rača river (where people believed in little lights called svetinje and witches who made men lose their way in the night so they could only come back home in the morning).

The songs brought to life stories about terrible creatures and Turkish invasions, as well as stories about important places or bridges (such as the bridge towards Jablje, previously known as the Viennese bridge, because the people of Vienna supposedly crossed it when on pilgrimages). This historical and mythological tradition was complemented by stories about people who were petrified, and sometimes (though rarely) also about those who lived in castles, like the lord of Jablje, whose head rolled backwards and who was saved only after building the church in Loka. These stories then transitioned into modern experiences through plays about Adam Ravbar and others, which were supplemented by singing parts.

In addition to the tradition of distant decades, this collection of songs also echoes some more modern gatherings that brought with them new songs. Social gatherings with songs were sometimes transferred into factories, and these songs can sometimes even contain traces of the Second World War – like a mocking song sung by a female partisan about the people of Domžale. Here and there, songs sprung up in the inns along former trade routes – sometimes as drinking songs, and sometimes as stories about long-ago heroes or farewells preserved in military songs.

The selection of songs thus represents different times in the period when people mostly worked in Domžale factories and ploughed their own (or community) fields. To a large extent, these are songs about the past, with love songs as a reflection of the life of the young, and the narrative ones as traces of the gatherings of different generations. The coexistence of the young and the old so frequent during labour was also made possible during ceremonies related to death and burial. At the time when these recordings were made, there were no morgues in the countryside and people kept vigil at home. During vahtanje, the wake, people sung pious songs, but also some narrative ones about legends and myths and special family destinies. Some places even preserved lyrical considerations of life and death characterized by baroque symbolism, and ballads that refer to the most distant of times.

The rituals associated with singing were preserved in the representations of the stages of life at weddings, although they were less pronounced. People still knew some wedding (vohcetna) songs, such as Bratec od Ljubljance (The brother from Ljubljanca) or the song Delaj se, delaj, beli dan (Rise, oh rise, the light of day) traditionally sung in the early morning after the wedding), but were no longer aware of their ritual role. The rituality was more familiar to people when it came to carolling at Christmas and New Year time or on Epiphany. For political reasons, carolling mostly only lived on in memory during the decades when the recordings of the songs in this collection were made.

The carols that the singers still remembered preserved not only fragments of former Christmas plays transferred from the churches to local carol rounds, but also musical carolling. The musicians from Goričica pri Ihanu (who performed musical carols during St Stephen’s Day and Candlemas in regions reaching as far as Ljubljana, Celje and Kranj) represented in a special way the connection between straw-plaiting and the singing tradition. This connection is the connecting and most prominent feature of the selected set of songs and is also on the cover of the presented publication itself, on which we see a depiction of the carolling of these musicians.

The connection between straw plaiting and the singing tradition is also expressed in the order of the songs, which is based on the established typology. First there are the old narrative songs, then followed by ritual ones from carols to funeral songs, the abundance of which hints at the preservation of the wakes. They are complemented by two rhythmic texts, religious hymns and moralistic songs. After them come military songs, followed by a series of love songs, some of which emphasize humour while others have an erotic undertone. Humorous and mocking songs resemble them in terms of content, while the patriotic songs that follow represent their complete opposite. The set also includes children’s songs and songs for children and is rounded off by a humorous drinking song and a medley of toasts which, beginning with Ta družba naj živi (May this company live forever), calls to new social gatherings in the company of the selected songs.